Rare earth elements are essential for modern technology, but their similar chemistry makes separation difficult and expensive. Now researchers are exploring new technologies to streamline processing and bring down costs.

- Rare earth elements underpin modern technologies but separating them is slow, costly and dominated by China due to entrenched processing infrastructure.

- Their similar chemistry makes purification difficult, forcing plants to use hundreds of solvent extraction cycles that drive up cost and energy use.

- Researchers are exploring alternatives including biomimetic ion‑selective membranes, electrokinetic separations and ionic liquids to boost efficiency and reduce chemical consumption.

- These emerging approaches show promise but require significant development before they can be scaled to industry, where low cost and high reliability are essential.

This summary was generated by AI and checked by a human editor

The rare earth elements are a staple of modern technology and electronics. Discovered throughout the late 18th and 19th century, this collection of 17 elements – comprising the lanthanides plus scandium and yttrium – were initially little more than a chemical curiosity, difficult to purify and with seemingly no useful applications.

However, advances in spectroscopic techniques and quantum understanding catalysed a revolution in the mid-20th century as previously hidden properties came to light. The lanthanides are the first elements which contain a partially filled 4f orbital and the unusual characteristics of these contracted, core-like orbitals give rise to a number of unique properties. ‘The optical properties derive from the electronic states of the different 4f configurations, the magnetic properties arise from the large number of unpaired electrons, and together with the unquenched orbital angular momentum of the 4f shell, this results in material qualities that aren’t accessible in other parts of the periodic table,’ explains Eric Schelter, a coordination chemist at the University of Pennsylvania in the US.

Today, these unique attributes are exploited in almost every aspect of modern life, from smartphones and digital displays to solar panels, wind turbines and medical imaging. But this explosion of applications over the last 60 years has prompted a surge in demand which current processing capabilities outside China struggle to meet. Mining, extracting and separating these elements is a long and expensive process, but sustained investment in this infrastructure has enabled China to dominate the global market, recovering these valuable metals more efficiently and economically than other nations and creating geopolitical tensions around access to rare earths.

A difficult and dirty process

To compete with China and stabilise the rare earths supply, the rest of the world must capitalise on domestic reserves and streamline the production process from mineral to metal. But battling the innate chemistry and geology of these minerals is no trivial matter. While the rare earths are relatively abundant in the crust – ranging from cerium at 66ppm (similar to copper) to thulium at 0.52ppm (more abundant than silver’s 0.075ppm) – there are few geological processes which concentrate these elements together, explains Aaron Noble, a mining and materials engineer at Virginia Tech in the US.

Brazil, India, Australia and America all have substantial domestic reserves, but a typical rare earth deposit might contain just 2–4% of the elements of interest, making mining economically inefficient, even with the high strategic value of the purified metal. Mines therefore immediately concentrate these mineral ores on site through a process known as beneficiation. The raw material is ground down into fine particulates and the rare earth-bearing components separated out from less valuable rock by froth flotation, raising the concentration 10–50 times depending on the grade of the starting ore.

‘The second challenge is then extracting the rare earths out of that concentrated mineral,’ says Noble. ‘Most rare earths are produced from three or four types of resource – bastnäsite, monazite, xenotime and ion-absorption clays – the first three of these are very hardy minerals. They take a lot of energy to break the bonds and release the rare earths from the mineral matrix.’ Calcination, often at temperatures nearing 1000°C, converts these challenging phosphate and fluorocarbonate minerals into more tractable mixed oxides, and these are subsequently dissolved in concentrated acid to leach the rare earth ions into solution.

But the most significant bottleneck in the process comes when separating these dissolved ions from one another. The core-like nature of the 4f orbitals means these elements exhibit remarkably similar physical and chemical properties, leaving only minute differences by which to distinguish them during separation. Consequently, separation plants are forced to use an iterative sequence of solvent extraction steps, sometimes totalling several hundred cycles, to achieve full separation across the lanthanide series.

The isolated elements then undergo a final processing step to ready them for commercial applications and are either metallised for use in alloys or converted into versatile oxide and carbonate intermediates for incorporation into products such as glasses and lasers. ‘Overall, you’re looking at a very costly process to implement, and because of that cost, it creates this high barrier of entry that I think is foundational to the rare earth challenge,’ says Noble.

The struggle to separate

The bulk of this cost arises from the separation step. On the face of it, the solvent–solvent extraction sequence is analogous to a typical liquid–liquid extraction in organic synthesis: a valuable product in an aqueous solution preferentially dissolves in an immiscible organic layer when combined, separating the product out from the other unwanted components in the initial aqueous mixture.

In the case of rare earth refining, the highly acidic rare earth leachate is blended with a kerosene organic phase containing a phosphoric acid-based extractant designed to chelate rare earth ions from the mixture. ‘It’s just an ion-exchange equilibrium between the rare earth and the extractant,’ explains Tommee Larochelle, chief technical officer at L3 Process Development in Quebec, Canada. ‘When you extract the rare earth into the organic phase, you release H+ to the aqueous phase, which favours the reverse reaction.’

A lot of companies only want to recover and market four of the 17 rare earth elements

Each of the rare earths has a subtly different affinity for the extractant, meaning those with the greatest affinity displace the other elements back into the aqueous. ‘Every element has an equilibrium pH – we call it pH50, where 50% goes in the organic and 50% stays in the aqueous – and the heavier the element, the lower the equilibrium pH,’ explains Larochelle. The resulting organic layer is therefore slightly enriched in a subset of the lightest rare earths in the mixture. This separated fraction still contains a mixture of rare earth ions and is subsequently re-extracted by stripping the metals back into an aqueous solution and repeating the sequence. Successive cycles gradually concentrate each rare earth in turn, isolating the elements in order of ascending atomic number at progressively lower pHs.

But the sequential nature of this process is intrinsically inefficient and further contributes to the flawed economics of rare earth refining, says Larochelle. ‘A lot of the projects I work on, they only want to recover and market four of the 17 elements – neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium and terbium – everything else actually has a negative value and they’re only isolated as a means to access those four,’ he explains.

Inspired by nature

With such small differences between neighbouring ions, there’s seemingly little to leverage to enhance the separation. However, selective transport of metal ions is an art nature has been honing for millennia and could offer one potential solution to this problem.

‘Membrane protein channels can do outstanding separations because they rely on more than just the size for separation,’ explains Manish Kumar, a membrane chemist at the University of Texas at Austin in the US. ‘For example, the potassium channel allows potassium but not sodium through with a selectivity of 78:1.’ Membrane channels achieve this gating effect by manipulating the water environment surrounding ions as they pass through, creating an energetic advantage for specific ions via coordination with the channel structure.

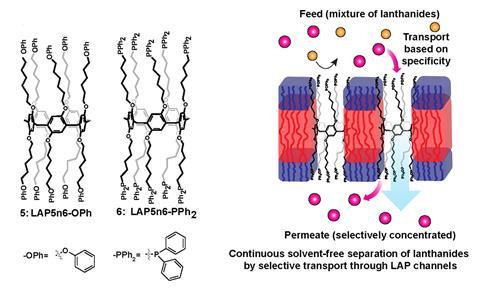

Drawing upon this principle, Kumar designed a middle lanthanide-selective artificial channel comprising a central pillar[5]arene band appended with diphenyl phosphine oxide ligands. The pillarene scaffold is the ideal size to coordinate lanthanide ions, which range in size from around 106pm to 86pm, and specifically favours coordination with the middle lanthanides. The surrounding diphenyl phosphine oxide ligands repel other contaminating ions such as calcium and magnesium, while oxygen functionality within the channel cavity blocks the passage of protons, maintaining a proton gradient across the membrane.

In preliminary experiments, the hourglass-shaped channel exhibited a 140-fold preference for terbium over lanthanum and a 70-fold preference for terbium over ytterbium – both substantial improvements over solvent extraction separations. ‘We don’t have complete proof for this, but we think it’s because the middle lanthanides have the most dynamic water,’ explains Kumar. ‘As the lanthanide reaches the centre of the channel, it has to get rid of its water so it can squeeze through. For mid-lanthanides like europium and terbium the water is very dynamic, but for the other ions, it’s too rigid and the exchange is very slow so they have a harder time getting through.’

The approach is still in the early stages and the team are currently working with a 1cm2 membrane in a small electrodialysis setup. For the time being, their main interest is in unpicking the fundamental chemistry governing the channel’s selectivity, rather than developing the channels for commercial use, and Kumar is keen to investigate whether tuning the system via a combination of the central ring size and pendant ligands could lead to tailored or more discriminating separations in future iterations.

Long term, he hopes that this methodology could address some of the existing challenges in industry but cautions that scaling these promising initial results will require some substantial work first. ‘I’m pretty confident we can scale the membrane-making process. It’s just expensive so we’ll have to figure out alternative materials,’ he says. ‘The system design for real-world applications is not clear. Selective electrodialysis has not been proven for large-scale mineral purification ever so the big platform technology is missing.’

Speed not stability

The rate of water exchange is an important discriminating factor in Kumar’s approach. On the whole, however, the kinetic disparities between elements are relatively underutilised in existing separation technologies. The majority of methods, including solvent–solvent extraction, rely on thermodynamic equilibria, exploiting subtle differences in the properties to shift the equilibrium position towards a specific product.

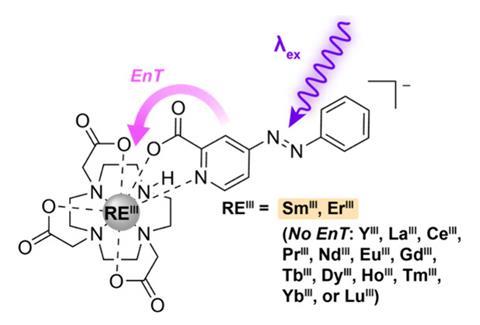

For Schelter, looking at the maths, this oversight seemed like a missed opportunity. ‘If you look at the Arrhenius equation, the energy difference appears in the exponent, so a small energy difference can translate into a large difference in rate,’ he explains. Incremental changes in chemical properties (such as Lewis acidity or hydration enthalpy) are therefore quickly magnified across the series by focusing on rate rather than stability. So perhaps with the right reaction design, these variable kinetics could be leveraged into a clean reactive separation, he postulated.

![The separation of rare earth elements not by thermodynamic but by kinetic methods is feasible based on the difference of the oxidation rates of [RE(TriNOx)thf]/[RE(TriNOx)] upon oxidation with [Cp2Fe][BArF]. TriNOx3−=[{2-(tBuN(O))C6H4CH2}3N]3−; BArF=tetra[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate.](https://d2cbg94ubxgsnp.cloudfront.net/Pictures/480xany/3/4/2/545342_anie201706894toc0001mcopy_726399.jpg)

The team opted for an electrochemical approach, using rare earth tripodal hydroxylamine (RE(TriNOx)) complexes previously developed in the group in a series of simple oxidation reactions. ‘The redox active part of the ligand is intimately tied to the metal centre, so the potential for that oxidation process is adjusted by the identity of the rare earth,’ explains Schelter ‘The oxidation process therefore occurs at a different rate for each metal cation, hence the electrokinetic aspect.’

But crucially, cyclic voltammetry experiments revealed that the ligand oxidation – which occurred faster for heavier lanthanides, mirroring the trend in Lewis acidity – was followed by irreversible dimerisation, pulling the rare earth complex out of the redox equilibrium to effect the separation. ‘Because the potential differences are small, there’s usually the opportunity for the system to just re-equilibrate,’ says Schelter. ‘But as it undergoes a chemical change too, the product is locked away in this new chemical form which then protects it against remixing.’

The group tested this electrochemical process on a series of binary mixtures, enriching 50:50 blends of Eu/Y and Yb/Y to 86% europium and 90% ytterbium respectively, and are now investigating methods to combine this kinetic distinction with a physical phase change for the trapped product. This transfer step would be a key requirement to ensure that the separation was practically straightforward at scale, Schelter explains.

At present, the approach is still in the discovery stage and Schelter is excited to first explore the wider potential of this kinetic strategy, notably how larger rate differences between photochemical excited states could be leveraged to achieve even cleaner separations. ‘It’s early days. We’ve demonstrated that the idea can work, but we need to further understand the combinations of ligands and rare earths and optimise the capability of these molecules to affect the transport between the phases,’ he says. ‘I think it will be a very strong candidate for commercialisation because it has the potential to deliver capabilities that the conventional technology can’t.’

Upgrading the original

Ultimately, to have any significant impact, these approaches need to be tailored towards the specific demands of industry-scale separations: low cost, excellent reliability and a good safety profile. The technological readiness of these new methods is not yet at a stage to compete with solvent–solvent extraction but ionic liquids are perhaps the closest to integrating into existing processing infrastructure.

Rather than developing a new separation process from scratch, these liquid salts replace components in the organic phase of typical solvent extraction procedures, operating by a slightly different mechanism to boost the efficiency of partitioning. ‘There are two categories: ionic liquids that are meant to replace the kerosene carrier, and the extractant version which replaces the acidic extractant to recover the rare earth from the aqueous,’ explains Larochelle. ‘The idea is that, instead of having an equilibrium reaction based on the cation exchange, the ionic liquid extractant can extract both the rare earth and the anion, and therefore there’s no hydrogen exchange.’

Theoretically, this alternative mechanism cuts acid and base consumption by a factor of 10, simultaneously enabling the organic phase to extract up to 50% more rare earths at a time. ‘You also get higher separation factors because of this different mechanism. So in a plant design, that means you need fewer units to get the same degree of separation,’ says Noble.

Ionic liquids could help achieve electrolysis at much lower temperatures

But he cautions that ionic liquids are far from a panacea and there’s still a way to go before they are ready to make the jump from pilot plant to commercial production. These solvents are often not commercially available, with those that are generally too expensive for industrial-scale consumption. Performance stability is also an important concern as many ionic liquids dissociate into their constituent ions at the low pHs required to dissolve rare earths, while safety and environmental considerations must also factor in to the choice of solvent. Overall, a number of procurement, processing and engineering challenges remain to be addressed before these liquids are ready for introduction into the infrastructure.

For Larochelle, ionic liquids are unlikely to replace kerosene and organic extractants soon, although he is hopeful that the industry can begin to substitute some examples into existing refinement circuits. However, there is greater potential for advances in ionic liquids and related technologies to have a transformative impact on other parts of the rare earth production process, he says. ‘I think the opportunity to use ionic liquids to metallise the rare earths once they’re separated is very significant. We could achieve electrolysis at much lower temperatures, probably around 125–200°C instead of 1000°C,’ Larochelle explains.

The criticality of rare earths boils down to a problem of supply and demand so improving the economic feasibility of existing resource bases through new separation technologies will be a key part of stabilising the world market. With global consumption only set to rise, it’s more important than ever that we continue to develop these methods now, creating an array of options for western industry to implement as it continues to streamline the rare earths process in years to come.

Victoria Atkinson is a science writer based in Saltaire, UK

No comments yet