A combined approach to nanofabrication has enabled researchers to construct elaborate 3D architectures from almost any material at a minute scale. The new technique blends conventional two-photon polymerisation (2PP) nanoprinting with laser-driven optofluidic assembly, drawing from the strengths of each method to create a versatile and multi-media fabrication mechanism.

Nanostructures often exhibit distinct properties compared with their bulk analogues as surface and interface interactions dominate the material’s chemistry. These unusual behaviours have found wide-ranging applications, not just in nanoengineering, but fields as varied as medicine, robotics and catalysis. However, constraints around both the choice of suitable materials and the flexibility of shaping and geometry remain key bottlenecks in the design of more complex and versatile nanodevices. Two-photon polymerisation is a precise and high-resolution 3D printing technique, but is generally limited to extremely specialised polymers. Conversely, self- or directed-assembly works with a wider variety of substrates, but struggles with freeform shaping and high yield.

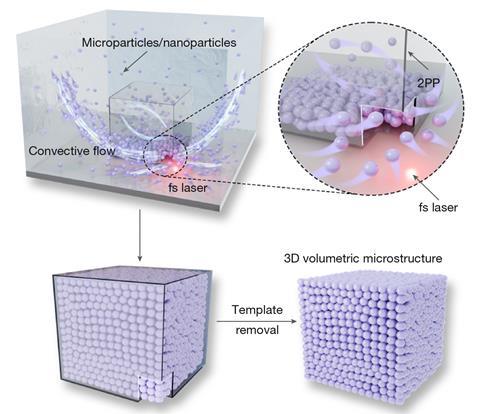

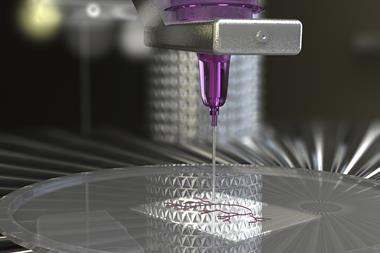

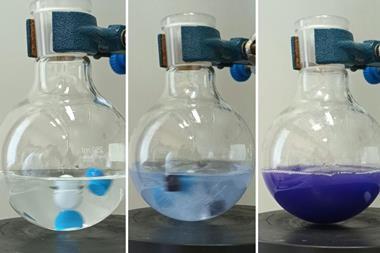

But, by breaking the fabrication process into two sequential steps, Mingchao Zhang and his international team have now combined the strengths of each of these approaches. The team first designed the shape of the required nanounit, printing a precisely-formed hollow 3D template using 2PP. This mould is then submerged in a suspension of nanoparticles – including metal oxides, carbon nanomaterials and quantum dots – and the team focus a femtosecond laser by the opening of the template to trigger assembly. The laser pulse creates a localised thermal gradient that causes the nanoparticles to flow into the mould where they settle into the shape designed in the 2PP step. The outer casing is then removed in a post-processing step, leaving a freestanding 3D structure in the chosen material.

‘This decouples geometry from chemistry,’ explains Zhang, who is based at the National University of Singapore. ‘Our method is broadly compatible because we are not relying on a specific photochemistry to form the final structure. Instead, the laser creates transport and confinement-driven packing, so the main requirement is that the material can exist as a stable dispersion of particles.’

This integrated methodology even enables sequential multi-material fabrication, opening the door to the design of more complex, multi-functional devices. ‘Once one material is densely packed inside its templated region, it becomes mechanically and energetically stable,’ says Zhang. ‘After that, we can wash away excess particles, switch to a different particle suspension, and assemble the next material in a different location or segment, without remixing the earlier particles.’

To demonstrate the potential of this new approach, the team fabricated a series of mixed-material microdevices, including valves capable of separating nanoparticles of different sizes, and light-driven microrobots that could have applications in sensing and bionics.

The versatility of this combined approach has impressed other researchers in the field. ‘Compared to other concepts where tailored resins are required, this work unlocks a different dimension for 3D printing that presents its own route for versatile multi-material manufacturing,’ says Jonathan Fan, an optical engineer from Stanford University. ‘The assembly of nanoporous materials, in particular, has broader potential in membrane-based devices and systems.’

‘The theory is really impressive. The authors elegantly analysed the key driving forces for particle assembly and provided very nice experimental evidence to support the theory,’ says Xiaoxing Xia, a nanofabrication scientist at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. ‘The proof-of-concept devices are interesting and inspiring for readers to brainstorm. I think the next step will be finding the right application for this method.’

Zhang and colleagues have already investigated how reaction parameters such as solvent and surfactant choice influence the speed and stability of fabrication and are continuing to work on the theory which underpins the method. ‘I want to establish predictive design rules that connect solvent choice, particle interactions, flow conditions and template geometry, so the process becomes programmable rather than empirical,’ he says.

References

X Lyu et al, Nature, 2026, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-10033-x

No comments yet