Rising energy costs, supply shortages and extended delivery times triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia–Ukraine war have had a ‘profound effect’ on science facilities across Europe, according to a key body that advises European policymakers on research infrastructure.

The European Strategy Forum on Research Infrastructure (Esfri) notes in its latest report that synchrotrons have been the most affected by these challenges, with five out of 10 reporting a planned interruption of operations. The report is based on responses to a survey sent to research facilities in December 2022.

According to the 116 survey responses, the most common issue faced was the impact on finance caused by increased energy costs, with energy-intensive sites such as synchrotrons, computing centres, accelerator-driven particle sources, neutron facilities, research reactors, and lasers being the worst affected.

Another issue was the shortage of key supplies, including the gases helium-3, nitrogen, argon and xenon, and materials previously supplied by the Russian Federation, including rare isotopes of calcium and cobalt.

Delivery times have also increased substantially, with some critical equipment taking over six months to arrive on site. Esfri notes that this is having a direct impact on timelines for the construction and upgrades of infrastructure projects and is ultimately affecting scientific output.

John Collier, director of the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council’s Central Laser Facility (CLF), says that the supply chain problems described in the report were issues he and his colleagues were experiencing on ‘a daily basis’.

‘They manifest themselves in two ways; the first is just straightforward availability of stuff, which has gone from relatively straightforward pre-Covid, pre-Ukraine war to really quite complex,’ says Collier.

‘The second thing is cost, which for certain components has seen eyewatering increases compared to the pre-Covid world,’ he adds. ‘It’s almost like capacity has gone, stocks have gone, availability of raw materials has dwindled … it’s impacted the capacity of organisations to deliver.’

Cristina Hernandez-Gomez, who heads up CLF’s high-power lasers division, says that the loss of expertise due to people retiring or leaving work during the Covi-19 pandemic has also contributed to delays.

‘We ordered some crystals from the US … [but] they had lost two people that were experts in growing these crystals,’ she says. ‘They had to grow the crystal three times [and] it failed three times – which means now this crystal is 18 months late.’

Many of the materials required by major research facilities are bespoke and therefore only available from a small number of suppliers. Hernandez-Gomez says that for some components CLF has started approaching new suppliers to see if they can build them to the same specification so that it would have multiple suppliers to draw on. ‘But every approach you take that is novel comes with a price tag,’ she adds.

‘We had some critical components that we sourced in Ukraine, and that that has been held up,’ says Collier. ‘To their credit the Ukrainians managed to eventually get this stuff out to us through Lithuania, but it was non-trivial – it’s probably taken a year plus.’

Collier also highlights the impact that Covid-19 lockdowns had on being able to supply and install equipment.

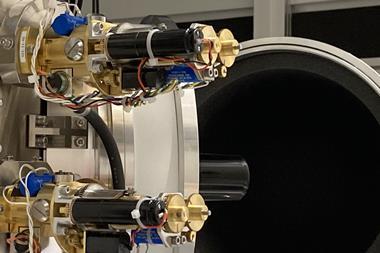

‘We installed a big laser [at the European XFEL] – a £10–12 million piece of kit, which took us 3 years to manufacture,’ says Collier. ‘We shipped it about two weeks before we had to go into [the first Covid-19] lockdown. [It] then took several years to get it installed and commissioned – we just did the first experiment using it a few months ago.’

Knock-on effects

Rajeev Pattathil, a group leader at CLF, says that he is particularly worried about the future impacts these challenges will have.

‘Let’s say something was costing £100k a few years ago, it’s now almost £400k,’ he explains. ‘That extra £300k would have gone on developing new technology to make the facility more internationally competitive … instead you have to invest that extra £300k in making sure that you can run the facilities – this will have a knock-on impact in future.’

The Esfri report makes several recommendations aimed at the European Commission and national policymakers to address these challenges, including developing response plans that would reduce energy consumption at major facilities as well as taking action to increase resilience and prepare for future crises. The report also highlights the need to set up specific measures to support the Ukrainian research community.

Esfri also suggests allocating additional funds and energy price capping for the most energy-intensive research infrastructure. However, Collier believes that additional funding in the UK is ‘unlikely at any significant level’.

‘We’re approaching a spending review – the tea leaves are saying it’ll be a one-year flat cash rollover until the general election has passed,’ he says. ‘I think the situation is going to remain pretty constrained for at least for the next year, 18 months.’

In the meantime, Collier says it will be necessary for research facilities to re-optimise their plans to minimise delays and, in some cases, choose not to pursue certain activities to make critical savings.

‘We have been buffered because we hold an inventory of spare components so by and large we’ve been able to weather that, [but] the cost of replacement is greater and therefore [it means] you won’t do something for the future, and that’s where the impact will be felt.’

1 Reader's comment