The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has recommitted to a goal from the first Trump administration to end animal testing at the agency by 2035, concerning some in the research community who say that this timeframe is far too ambitious. This policy change tracks a trend unfolding elsewhere in the world, including the UK and the EU.

EPA administrator Lee Zeldin – a lawyer-turned-politician who took the helm of the agency a year ago – made the announcement on 22 January and then signed a directive formally prioritising its efforts to reduce animal testing and ban it at the agency within nine years. The agency uses laboratory animal tests to evaluate the risk profile of chemicals, including pesticides and pollutants.

A ‘minimal amount’ of animal testing is still required to support statutorily mandated regulatory responsibilities to demonstrate new chemicals safety in the US, the agency acknowledged. But Zeldin suggested that animal testing ‘may not be necessary just a few months from now’. He said the agency has found, over the last year, new alternative methods that can replace such animal testing and expressed confidence that it will continue to discover more in the months and years ahead.

‘EPA will work in targeted ways to further reduce [animal testing] however possible and collaborate with other government agencies, researchers and advocates to develop and validate the use of alternative methods for toxicity testing,’ Zeldin stated. ‘We’re going to continue to aggressively pursue our goals in identifying what’s referred to as NAMs [new approach methodologies] and new innovation.’

Last year, for the first time, the EPA’s Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention (OCSPP) used alternatives to animal testing in its cancer tests for two phthalate chemicals. This spared an estimated 1600 mice and rats from lab experiments, Zeldin said.

Further, the agency said in April 2025 that there were 466 lab rodents in its Office of Applied Science and Environmental Solutions, which operates the agency’s animal care facilities, and that number had fallen to just 41 as of mid-November.

An official commitment to reduce animal testing at the EPA and ban it by 2035 was launched in 2019 under former administrator Andrew Wheeler, who ran the agency during Trump’s first term as president. But during his announcement Zeldin accused the Biden administration of ignoring this phase-out deadline. He said he has now brought back this initiative based on his personal interest in the issue and work with animal rights groups such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (Peta).

Cell-based models still need work

This new EPA announcement follows years of collaboration between the agency and Peta scientists, including co-authoring publications on animal models in cancer tests.

The National Association for Biomedical Research (NABR), which advocates for the humane use of animals in biomedical research, commended the agency’s efforts to reduce animal testing. However, Matthew Bailey, NABR’s president, described reviewers at the OCSPP as ‘the last line of defence’ between the American public and new chemicals. He says gold standard science uses the best available methods to test a chemical’s safety, including NAMs and animals. ‘There are currently not enough scientifically validated, standardised NAMs to fully replace animals in chemical safety testing,’ Bailey adds. Therefore, he suggests the 2035 deadline to phase out animals in chemical safety testing should be viewed as ‘aspirational’.

Jamie DeWitt, an environmental and molecular toxicologist at Oregon State University who studies the immune system, has mixed feelings about this move away from animal models to assess chemicals. ‘The immune system is complex and requires the interaction of many different cells and signals, which makes a whole animal model essential for truly understanding impacts on the ability of the immune system to function,’ she tells Chemistry World. ‘There are cell-based models available for some immune functions, and some are quite good, but they still need to be validated to ensure that they can predict the same outcomes as whole animal models.’

DeWitt notes that developing and validating non-animal models is time-consuming, suggesting that 10 years probably isn’t enough time. ‘I’ve been working on a cell-based immune assay for almost four years and I’m not even close to having it ready to validate,’ she states. ‘I think that there’s promise in many new approaches to identify hazards of chemicals and support risk assessments, but validation is essential and takes time.’

Robin Lovell-Badge, a medical scientist at the Francis Crick Institute, echoes DeWitt’s sentiments. He says it will be possible to replace a substantial proportion of animal testing for chemicals, as well as drugs, if regulations and guidelines are put in place to permit and encourage the use of NAMs. But Lovell-Badge emphasises that these tests will need to be validated for efficacy and safety in animals or humans.

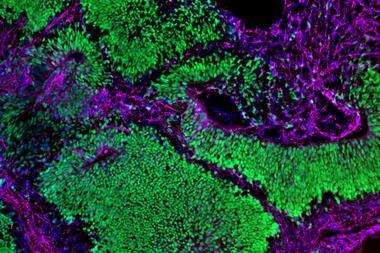

‘Most NAMs being developed for such tests focus on a specific cell type, tissue type or organoid,’ he states. ‘These will not be, and can probably never be, representative of every tissue and cell type within the body, at different ages … and conditions, and also be able to reflect different physiologies.’ He asserts that complex systems and conditions, such as cancers, as well as the immune endocrine and reproductive systems, cannot be replicated using NAMs.

Industry ‘can confidently bring forward non-animal data’

The EPA’s action appears to be part of a larger movement within the US government to distance itself from animal experimentation. Last year, the US National Institutes of Health launched a new centre charged with helping to reduce the use of animal testing in drug discovery by developing lab-grown tissue models called organoids that can mimic the structure and function of human organs. That commitment came just a few months after the US Food and Drug Administration announced its intention to phase out animal testing for new monoclonal antibody therapies and other drugs, and the NIH rolled out a new initiative to decrease reliance on animal models in the biomedical research that it funds.

Beyond the US, a few months ago the UK government published a roadmap to speed up alternatives to animal testing in research, backed by a £75 million commitment to advance new testing methods for products. The European Commission has said it will finalise a roadmap to reduce animal testing and help ‘transition towards an animal-free regulatory system’ by March 2026, possibly integrating new test methods into its Reach chemicals regulation.

No comments yet