The UK government has published a roadmap to speed up alternatives to animal testing in research. It has committed £75 million to advance new testing methods for products and promises to streamline regulation. However, many in the scientific community believe that replacements for all types of research won’t be possible in the foreseeable future.

The strategy commits £60 million for a data, technology and expertise hub to promote collaboration and a separate centre aimed at simplifying regulatory approval for products. The Medical Research Council, Innovate UK and Wellcome will receive £15.9 million to advance human in vitro models, such as organ-on-a-chip systems that mimic how human organs work using human cells.

The government has also committed to ending regulatory testing on animals to assess new products for potential skin and eye irritation and skin sensitisation by the end of 2026; ending botox strength tests on mice and using only DNA-based lab methods to detect contamination of medicines by viruses or bacteria by 2027; and reducing pharmacokinetic studies – which track how a drug moves through the body over time – on dogs and non-human primates by 2030. Other commitments include providing training in NAMs for early-career researchers from next year, publishing research priorities at least every two years from 2026 and strengthening research funders’ commitment to alternative methods. Science minister Patrick Vallance will chair a new committee to oversee progress.

This strategy sets out an ambitious roadmap, says Nicola Perrin, chief executive of the Association of Medical Research Charities. ‘There’s a clear focus on removing barriers, supporting underpinning enablers and facilitating data-driven innovation. However, importantly, there’s also a continued commitment to the use of animals in research where no other options are available. This continues to contribute to many medical advances which save and improve the lives of millions of people. It is critical that this isn’t put at risk.’

Both animal research and non-animal methods (NAMs) must go hand-in-hand to achieve advances, stresses Sarah Bailey, a bioscientist at the University of Bath. ‘There is, and always has been, a clear ethical drive to only use animals in research where there are no alternatives. Most scientists use a combination of approaches that include NAMs, such as cell-based assays, to test if a new drug is binding to the intended protein target or computer modelling of pharmacokinetics.’ But animal research is still needed in several areas. ‘Fundamentally, if we want to know what a body is going to do to a drug, and what the drug is going to do in the body, then we need to use animals.’

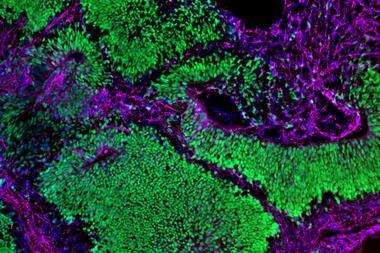

Robin Lovell-Badge, a medical scientist at the Francis Crick Institute, agrees there are many areas where ‘no current NAM gets anything close to the real biology’. These include complex areas of biology, such as the brain and behaviour, reproductive, immune and endocrine systems, and tumour biology. Studying ageing, altered physiologies or environmental effects also requires animal models.

While he welcomes many aspects of the strategy, he says phasing out all animal research is ‘a fairytale, not a sensible policy’. ‘There are aspects of using NAMs that could be sped up and for which additional funding would help enormously. But this is largely for testing toxicity and pharmacokinetics, which are relatively simple assays where current regulations stipulate testing in animals. Changing the regulations with a need to show safety would help adoption of NAMs in such cases.’

Overall, however, Lovell-Badge believes the strategy is geared too much towards regulatory testing, where the goals are more achievable, rather than discovery science. ‘Pushing this agenda too hard will demotivate the excellent animal technologists who are essential to much of the work on animals. They are already upset by some of the recent changes made in the way the review and oversight of animal research is conducted by the Home Office. Any (premature) loss of these skilled and conscientious people will severely affect the UK’s ability to conduct competitive/world-leading biomedical research.’

No comments yet