Librarians and physicists at the University of St Andrews in the UK have developed a portable device that can quickly and cheaply detect the presence of toxic pigments in Victorian-era book bindings.

The researchers developed the detector to identify a bright green pigment known as emerald green that may contain arsenic. Frequent handling of contaminated books can lead to health issues like eye, nose and throat irritation, and potentially more serious medical effects.

‘The project began with the need to positively identify emerald green bindings in the University of St Andrews collections, using the analytical techniques available to us within the university,’ explained Pilar Gil, a chemist and heritage scientist who led the research and laid the groundwork for the technique. The ‘Eureka moment’ was discovering the unique reflectance pattern from emerald green pigment, she added.

Graham Bruce, senior research laboratory manager at St Andrews and one of the two physicists who developed this handheld screening tool, was tapped to help develop the new device because of his previous applied spectroscopy work, mainly to identify counterfeit whiskeys.

In this case they were looking for a compound – copper acetoarsenite – that was widely used in the 19th century but only recently discovered to also have been used in book bindings. Unfortunately, this pigment is particularly friable, so crumbles easily releasing arsenic into the air.

‘Over the last year or so we’ve developed this very small tool which measures the key parts of the spectrum that we need to identify this compound,’ Bruce tells Chemistry World. ‘Not all green books of the correct time period contain this compound … and what our tool does is to combine information from the visible part of the spectrum and the infrared part of the spectrum so that we can determine whether this pigment is present in the book binding or not.’

The advantage of this new screening device, he says, is that it can be pointed at a book and a green or red light displays within a fraction of a second to indicate whether or not the book contains this pigment.

Besides being fast and easy to use, the instrument is also non-destructive. ‘Because it’s light, and relatively low intensities of light, it doesn’t cause any additional breakdown of the materials in the book,’ Bruce explains. ‘If you want to do something like x-ray fluorescence, that usually involves removing a part of the material that you want to interrogate.’

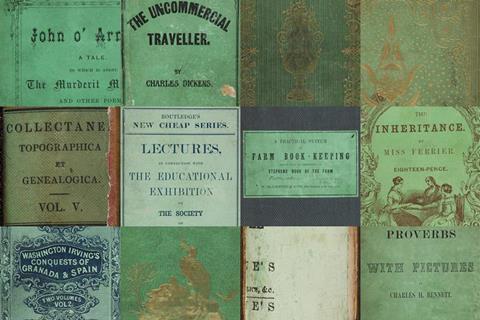

Pigment contamination concerns have recently caused libraries across the world to cut off access to portions of their book collections, pending specialised, costly and time-consuming testing. Last year, the French National Library reportedly removed four 19th-century books from public access after tests indicated that their covers and bindings contained emerald green. According to Bruce, the University of Bielefeld and several other German universities isolated approximately 60,000 books, pending toxicity testing.

Also in 2024, chemists at Lipscomb University in the US pulled more than two dozen of the school’s Victorian-era books from circulation after tests revealed that they contained dyes with potentially dangerous levels of lead and chromium. They sealed the books and instructed librarians to use gloves and heavy-duty masks if working in a confined space with these materials.

At that time, the Lipscomb team was interested in exploring the use of portable x-ray fluorescence to establish a standardised analytical protocol to test potentially toxic book covers.

The article was updated on 19 June 2025 to amend Pilar Gil’s title.

No comments yet