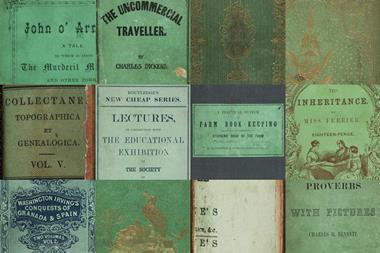

A shared reference that we risk losing in a digital age

I worry about the disappearance of books from universities. A recent visit to our science library reminded me of how many stacks of books we have replaced with desks for student computers. No doubt it is a sign of my age that the solidity of books, their feel and their psychogeography makes them feel more trustworthy than the glut of results and irrelevant advertising that is returned by internet searches. And my sense of being old was reinforced by some students who had never heard of one of the legendary authors of practical chemistry: Arthur Vogel.

Vogel was born in Dębica in Galicia, today southern Poland. His family emigrated to London, UK, in 1906, settling in Wellclose Square in Shadwell in the London docklands. It was a rough, multicultural area populated by a significant Jewish community and with many houses either owned or occupied by transient merchant seamen.

Although his family were orthodox Jews, Vogel was sent to the Davenant Foundation School in Whitechapel, a charitable institution intended to educate boys regardless of religious belief. In 1888 a chemical laboratory and workshops had been built in the building in Whitechapel Road and it may have been here that Vogel developed his passion for chemistry.

Vogel was an undergraduate at East London College (today QMUL) where he began research with the polymathic chemist, educator and historian of chemistry James Riddick Partington. In 1925 he reported the preparation of a deep blue, very moisture-sensitive sulfur sesquioxide, S2O3; it was non-trivial chemistry all carried out with carbon dioxide as the blanketing gas, before the arrival of Schlenk techniques. A Beit Fellowship later opened the doors to Imperial College, where Jocelyn Field Thorpe had assembled one of the leading concentrations of organic chemists in Britain.

In the 1920s chemistry was being transformed by the new physical ideas of Svante Arrhenius and Wilhelm Ostwald, that, before the rise of spectroscopy, began to provide real insight into structure and bonding. In 1924, Samuel Sugden, a physical chemist at the Woolwich Arsenal, proposed a new parameter he called the parachor, a measure of the molar volume of a molecule that could be derived from the surface tension and the density. By combining values associated with different functional groups, parachors could be used to infer molecular structure.

Vogel’s work with Thorpe focused on this early physical organic chemistry. Because chemical suppliers like Kodak, let alone Aldrich and so on, were many years in the future, almost every compound he studied had to be prepared from scratch and meticulously purified. In the introduction to his Practical Organic Chemistry (1948), which is the heir to Ludwig Gattermann’s earlier ‘Cookbook’, Vogel paid tribute to the four years he spent in Thorpe’s lab learning both technique and a wide range of synthetic methods. His productivity in this period was phenomenal and he was awarded a Doctor of Science in 1929.

Making a name for himself

After a brief period in industry, he took a lectureship in Southampton in 1930, at which point a subtle change appears in his publications; while previously he’d gone by Israel, he now added Arthur to his name, with Israel becoming a middle initial. Was this a response to the political winds of the time?

In 1932 he was appointed head of department at Woolwich Polytechnic (today Greenwich University) where he continued his work making physical measurements: parachors, dissociation constants, refractivities. At the same time he oversaw the teaching programme in his department, introducing new practicals and procedures to make sure that his students received a broad-based education across the whole of chemistry.

I’ve heard Italian chemists refer to ‘Il Vogel’

It must have occurred to him that there was a real dearth of laboratory handbooks that could support a student or a researcher who needed to conduct a particular type of procedure or analysis. Vogel began to compile what he had learned into several textbooks on qualitative (1936) and quantitative organic analysis (1939) and practical organic chemistry (1948). Reviews praised the lucid writing in the books, which covered the theoretical basis of the subject first, followed by detailed procedures and examples. There were clear line diagrams of apparatus, and many references to commercial suppliers of chemicals and glassware. There were several editions, and numerous translations. I’ve heard Italian chemists refer to ‘Il Vogel’, the volumes having become part of a shared experience for chemists globally.

As books disappear from open access shelves and growing numbers of software-generated pages replace them in our web searches I wonder whether we are witnessing a creeping hollowing out of our knowledge. I fear for the future of our libraries, the quiet places that bear witness to the slow, methodical, almost obsessive work of people like Arthur Vogel. Will the vast online repositories prove as robust as the great libraries of the past? And are we losing some of that shared psychogeography that is summed up by phrases like ‘Let’s look in Vogel’?

No comments yet