Does anyone blow glass in chemistry labs any more?

Does anyone blow glass in chemistry labs any more? There was a time when every chemistry department had a glassblower or two, and many research labs had a glassblowing station where students could seal off a sample and do quick repairs. What with interchangeable Quickfit glassware, and a steady contraction in technical support, glassblowers have got ever older and fewer in number. One recently told me that it took his apprentices six years before he could let them loose on commercial contracts, not much less than a research chemist. And few get much credit for their pains.

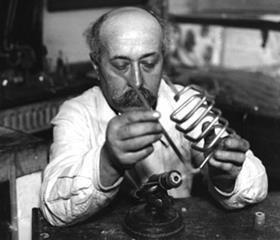

Henri Narcisse Vigreux was a rare exception. Born on 16 December 1869, in the village of Parly in northern Burgundy, France, he started as a lab boy at the Sorbonne’s Institute of Chemistry in Paris, and worked his way up the ranks to become head of glassblowing - though he would retain the title Garçon de Laboratoire well into his 50s.

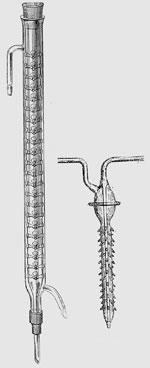

Unusually for a glassblower, Vigreux began to publish regularly in the chemical literature. In 1904, he described a beautiful and revolutionary reflux condenser (right) consisting of a water-jacketed tube, its inner surface studded at regular intervals with sets of ’plates and crowns’, pairs of four hollow indentations pointing towards the centre and downwards. The design demonstrates an instinctive feel for distillation and fractionation: the projections were designed to hugely increase the cooled surface area in contact with vapour, and any condensed liquid was deliberately returned to the hotter centre, promoting contact between vapour and liquid phases. The paper also described unjacketed versions of the patented kit, which could be bought from the Etablissement Leune, a firm remembered for its stunning Art Deco glassware designed by Paul Daum, but which also sold bespoke scientific apparatus, all from a workshop in a disused cabaret theatre.

Vigreux was fiercely proud of his invention, defending it against all rivals. When a 1913 paper described an unwieldy three-metre long distillation apparatus, Vigreux demolished the author’s claims by proving the superior performance of his own column, though it was only a quarter the length.

In the First World War, Vigreux was seconded to the research laboratories of the Office of Petroleum Supply. He found time to write Le Soufflage du Verre dans les Laboratoires Scientifiques et Industriels (Glassblowing in Scientific and Industrial Laboratories) to help researchers to make their own glassware. Published after his return to the Sorbonne in 1918, the book quickly sold out.

Vigreux’s renown grew such that in 1924, he was one of the inaugural recipients of the Meilleurs Ouvriers de France prize, given to the country’s greatest craftsmen, and in 1925 was invested Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur. He was now teaching across France, usually wearing a trademark hat to cover his close-cropped head. He published improvements to Kjeldahl flasks, analysis tubes, mercury diffusion pumps, and a beautiful, mad device in which a Vigreux condenser was topped by a water aspirator driven by the cooling water, thereby setting up air flow through the system. Vigreux argued that one could use it to carry out diethyl ether refluxes in open containers. The accompanying illustration of a Bunsen burner heating the beaker suggests organic solvents were thought rather less flammable then.

Most whimsical of all was a 'universal' condenser (left) which, to my innocent eyes, looks plain rude: a lavishly studded water-cooled probe that could be inserted into the neck of a heated flask without the need for joints or connections. The prototypes, Vigreux noted, were made by war invalids. He also detailed the manufacture of glass eyes for those disfigured in war. Shortly after his last publication in 1938, he retired to his home village of Parly, where he died on 25 October 1951. His book can occasionally be found in antiquarian bookshops but has been digitised for posterity. Vigreux’s column, on the other hand, is ubiquitous. There isn’t a synthetic chemist alive who doesn’t owe the purity of a starting material or an intermediate or three to this stunningly beautiful and elegant device.

Andrea Sella is a lecturer in inorganic chemistry at University College London. He thanks Mr. Pierre Pignat for his assistance with this article.

1 Reader's comment