Years as a practical chemist can come in useful when trying to unjam a dram

I have been a practical chemist most of my life but I have also worked as a showman, in fact as the brains behind the television physical-sciences presenter Magnus Pyke. Pyke was part of the Yorkshire Television (YTV) science show Don’t Ask Me in the 1970s.

In putting that show together, we were always trying to involve the public and seeking ways of making scientific knowledge relevant to everyday experience. And once we had a splendid chance. A man wrote to Pyke complaining that the glass stopper of his decanter had stuck, and he could not get at the whisky inside.

As a chemist, I had frequently had to wrestle with jammed taps, stuck stoppers, and other items of recalcitrant conical ground glass and I told the YTV science team that we could turn this into a powerful TV item. So we invited the man to come up to the Leeds studio, and to bring to his decanter with him.

Get me a hammer!

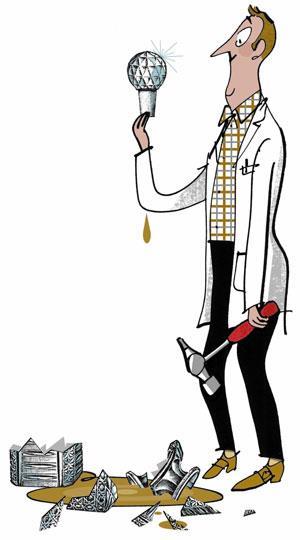

When he arrived, I looked at the decanter. Its stopper was indeed firmly jammed on, and I could not free it manually. ‘We simply have to get that stopper free!’ cried the TV producer. ‘I’ve been a chemist for years,’ I replied. ‘I know how to handle glassware. Get me a hammer!’ With understandable reluctance, the TV producer found a hammer, and gave it to me. I could easily have wrecked the whole item but I set to work.

My theory, developed over many years as a practical chemist, is that a stopper or a cone-and-socket joint jams because a little bit of grit gets into it. As a result, the cone does not quite fit the socket. Opposite to that particle of grit, the cone makes a solid contact with the socket, and is jammed and rigid. Any attempt to knock or rock it free in that direction is doomed.

However, at 90° to the grit particle the cone can be rocked very slightly. Accordingly, it is worth bashing the stuck joint with a hammer; but there is a particular direction for the most effective bash. You should try to hit the cone element at 90° to where the grit is. In that direction, the joint can rock slightly and loosen itself – well-judged hammering can free the joint.

Over the years, I have also learned that the intensity of hammering force needed to free a ground-glass joint can be surprisingly high. Luckily great experience, and my vast past tally of broken glass, did the job and I managed to get the stopper out of the decanter. The tense producer relaxed and we put the stopper back carefully, and began to build the TV item.

Putting on a show

I set up a number of demonstrations of freeing a jammed decanter-stopper, using some Yorkshire Television decanters. The first was simply to heat the neck, using a hot-air blower and even a flame. Pyke could explain that the heat expanded the neck of the decanter before it expanded the stopper inside, so that latter would come free. It did not work. Then we tried simple violent bashing; the stopper broke. Then we tackled the decanter our man had brought. To ‘free’ its stopper, Pyke showed a clever trick I had invented for the job: An electric razor, bashing gently 50 times a second, eased the stopper out. The decanter-owner’s astonished face as he saw Pyke free that stopper, made the whole TV item a delight.

And to celebrate, we all had a toast of the freed whisky before he left.

David Jones

No comments yet