Many researchers are now feeling the effects of additional emotional burdens

The Covid-19 pandemic has been labelled a mass global trauma event, with all-encompassing effects similar to that of the second world war. It remains too early to estimate the full impact of these events on the health or career progression of marginalised individuals, but early results highlight that many experienced significant challenges.

The international Women in Supramolecular Chemistry (Wisc) network began a programme of research into lived experiences of life inside and outside the lab in September 2020. Although it had not been designed to capture Covid experiences, the timing meant that it was perfectly situated to do so. The chemical science community shared the general shock of lockdowns and lab closures, with the corresponding challenges of home-schooling, isolation and keeping research groups going. To capture the emotional and embodied experiences that these situations produced, Wisc used a variety of creative and qualitative research methods.1 These data were collected through reflective work with research groups and collaborative autoethnography, alongside qualitative surveys that received responses from supramolecular researchers across five continents.

Autoethnography is the study of the self in relation to the social environment and context. It is commonly used to explore subjects that are sensitive, contentious and that have personal meaning to the researcher.2 Autoethnography demands a lot from a researcher more used to methods from within the chemical sciences. It interprets validity, rigour and repeatability differently; for example, an autoethnographic study gains validity by the researcher reflecting on their part in events and the impact and implications their actions have for those around them,3 and by being self-aware4 and honest about their vulnerabilities, privilege and position.5 It is an inclusive approach that incorporates viewpoints and knowledge beyond white, Eurocentric ideas.1 Collaborative autoethnography,6 where participants shared and compared experiences, allowed all concerned to see where there were resonances and added an element of accountability and rigour. Both the reflective work with research groups and collaborative autoethnography encouraged participants to share images and objects that represented their feelings – for example a crushed water bottle or over-stretched hair band might illustrate how the individual felt misshapen from stress.

The meetings gave the individuals involved space to reflect and process what they were experiencing

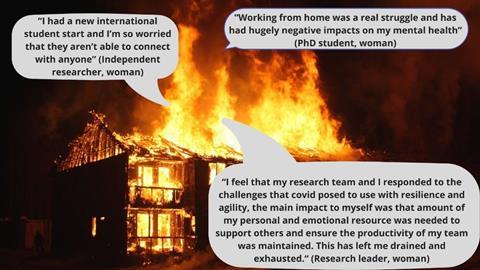

Wisc’s collaborative autoethnography group consisted of a diverse group of 12 members, all of whom identified as women, residing across the UK, US and Europe. They shared many things, such as how they managed their research groups’ time and tasks within the laboratory and took responsibility for their research groups’ mental health and wellbeing at the cost of their own, along with images of feeling burnt out, or continually fighting fires. The feelings of overwhelm they shared echoed those within the reflective research group meetings and survey responses from the wider community, allowing Wisc to show that these feelings were not just subjective experiences limited to a small group.

Across all three data sets it became clear that having split-group rotas, a lack of communication and lack of productivity in their research had negative impacts on the mental health of the majority of participants. Students shared the impact of not being able to see their team or socialise. Research leaders shared the emotional load they carried for their group. Furthermore, additional pressures were specifically felt by those with caring responsibilities regardless of age, career stage or gender.

Not every experience was negative. There were some people without caring responsibilities who found that Covid-19 had benefits to their mental health as pandemic restrictions allowed them more time for self-care and healthy activities. A female master’s student shared that ‘it also meant that I was able to look after my mental health a little better, having half of the day to do some healthy activities and spend time on myself’.

Our study methods themselves were designed to benefit the participants. The collaborative autoethnography group shared that they gained a sense of community and support from their peers during the research process. Their meetings gave the individuals involved space to reflect and process what they were experiencing, and so, rather than being another burden on their time, this programme of research helped to ameliorate the emotional load they carried. Similarly, members of the reflective research groups communicated that they felt as though sharing their experiences allowed them room to get on with the actual science.

The importance of community for women in academia and science is widely recognised.7–8 The emotional load of managing a research group through the pandemic was an unexpected burden that was borne unevenly across the academic community, which was enhanced for those with caring responsibilities. Wisc’s work suggests that a major tool to address the lack of gender balance and diversity in chemistry is to establish and grow networks of area-specific communities that allow space for members to reflect on and share their lived experiences so that they feel less isolated and alone. Although setting up and maintaining these spaces is work beyond the day-to-day, Wisc believes this model can act as a blueprint for other area-specific groups. Is there a need for this in your field?

Acknowledgements

Jennifer Hiscock, Jennifer Leigh, Cally Haynes, Anna McConnell, Claudia Caltagirone, Marion Kieffer, Emily Draper, Anna Slater, Larissa von Krbek and Charlie Hind contributed to writing this article

References

1 J S Leigh et al, Chem, 2022, 8, 299 (DOI: 10.1016/j.chempr.2022.01.001)

2 A Bochner and C Ellis, Evocative autoethnography: Writing lives and telling stories. Routledge, London, 2016

3 A Bleakley, Stud. High. Educ., 1999, 24, 315 (DOI: 10.1080/03075079912331379925)

4 J Leigh and R Bailey, Body, Mov. Danc. Psychother., 2013, 8, 160 (DOI: 10.1080/17432979.2013.797498)

5 J Leigh and N Brown, Embodied Inquiry: Research methods. Bloomsbury, London, 2021

6 H Chang, F Ngunjiri and K-A Hernandez, Collaborative autoethnography. Routledge, Abingdon, 2016

7 E Daniell, Every other Thursday: Stories and strategies from successful women scientists. Yale University Press, New Haven, 2006

8 E Yarrow, in Women thriving in academia, (ed. M Mahat). Emerald, Bingley, 2021, p 89

No comments yet