Politicians should not rush to ban neonicotinoids until field trials have proved that they are wiping out bee colonies, argues Mark Peplow

One thing’s for sure: the bees are not happy.

Since 2006, worrying numbers of worker bees have been deserting their hives, a phenomenon dubbed colony collapse disorder (CCD). Although apiculturists have noted for centuries that bees can suddenly disappear in this way, the problem has grown to unprecedented levels. Last year, commercial beekeepers in the US lost up to half of their hives.

The effects could go far beyond honey supplies. The US Department of Agriculture estimates that the nation’s bees are responsible for pollinating crops worth about $15 billion (£9.8 billion) each year.

Over the past decade, researchers have assembled a line-up of CCD suspects. Varroa destructor mites, for example, have long been in the frame, as they carry viruses that can weaken bees’ immune systems, or kill them outright. The Nosema apis fungus and Israeli acute paralysis virus have also been blamed. But it is possible that these are opportunistic infestations that gain a foothold in hives where bees are already weakened by some other factor. Could that factor be pesticides? A growing body of scientific evidence suggests that neonicotinoid pesticides could indeed be responsible for CCD.

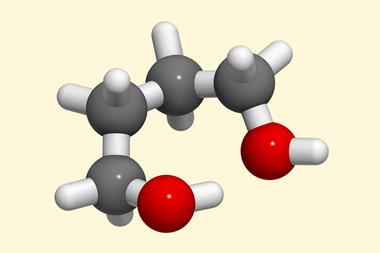

Since launching in the early 1990s, neonicotinoids’ advantages have made them one of the most widely used classes of pesticides in the world. Their effects are far more severe on insects than mammals and they are more potent that the pesticides they replaced, such as organophosphates and carbamates, so they can be used in significantly lower concentrations. And, unlike many other pesticides, neonicotinoids are often applied to seeds and soil, with a single dose spreading through the plant’s tissue to give long-lasting effects. But their days may now be numbered.

In 2012, several studies suggested that exposure to neonicotinoids killed off queen bees, and also made it harder for workers to navigate back to their hives.1-3 In March, UK researchers concluded that neonicotinoids impaired bees’ learning ability, potentially making them less effective foragers.4,5

Bumbling around

The growing concerns have prompted the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) to wade into the fray. In January, it published an assessment of three neonicotinoids – clothianidin, imidacloprid and thiamethoxam – concluding they posed an unacceptable risk to bees, and should only be used on crops that are not attractive to the insects. The European commission promptly called for a two-year moratorium on neonicotinoid use on flowering crops, although about half of the EU’s member states failed to support that motion in a vote last month. The proposal is expected to be appealed, though, and could still be enacted this summer.

It would be unwise to ban neonicotinoids without looking at the consequences

The big question is how closely these lab-based studies match real conditions: there are very few data about the true level of bees’ pesticide exposure in the field. The UK’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) attempted to fill that gap with field trials involving buff-tailed bumblebees. The report, published in March, stated that bees were routinely exposed to neonicotinoids, but found no significant impact on hive health. However, the trial has been widely criticised: this particular species of bee is not suffering significantly from CCD, for example.

The House of Commons’ Environmental Audit Committee (EAC) also disagrees with Defra. On 5 April it released its own assessment, broadly in line with the EFSA’s report. So what are we to make of this maelstrom of evidence and conflicting views?

On trial

Firstly, it is far from certain that a moratorium on neonicotinoids alone will save bees. Most experts agree that CCD has multiple causes and bee populations were on the wane in Europe before these pesticides were introduced, probably caused by the decline in flowering plants as agriculture intensified.

In the absence of scientific consensus, some (including the EAC) argue for a precautionary approach: suspend the use of neonicotinoids until further evidence exonerates them. But policymakers must also apply the same principle to any moratorium. Will farmers switch back to older pesticides that raise other environmental problems, for example? Neonicotinoids offer improved, convenient pest control – that’s why they so quickly came to dominate the market – so how will a moratorium affect crop yields? It would be unwise to simply ban neonicotinoids without looking more carefully at the potential consequences.

Further field trials are needed to assess the impact of these pesticides under routine farming conditions. If neonicotinoids are involved in CCD, such trials could also determine exactly how they are implicated.

Field trials are expensive – a single study could cost millions of pounds – but the costs are tiny compared with what is at stake for the agriculture industry. Both sides of the debate agree that we need evidence-based policy: so let us first gather that evidence, and then make policy.

No comments yet