Novo Nordisk is cutting 9000 jobs with the intention of saving around DKK8 billion (£1 billion) in annual costs, capping a turbulent year for the Danish pharma firm. The opinion of investors had darkened over the past year, after Novo struggled to meet demand for its obesity drug, lost market share to rival Eli Lilly and came under pressure from compounding pharmacies selling versions of its products in the US.

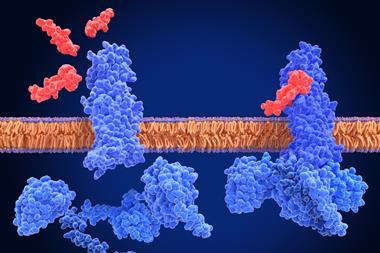

Novo was predominantly known internationally for its insulin products, until it began selling semaglutide in 2018 – branded as Ozempic for diabetes, then branded as Wegovy for weight management in 2021. Novo had first mover advantage on a new kind of drug that mimics the metabolic hormone glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which regulates blood sugar and appetite. Ozempic became a household name, with speculation around which celebrities were taking it for weight loss creating social media buzz.

Demand ballooned beyond what the company or market watchers had predicted. ‘In 2023, we realised that the demand was going to be significantly higher for obesity drugs. We’ve tripled the estimated market since 2020 and now talk about $120–150 billion, not $80 billion,’ says Rajesh Kumar, head of european life sciences & healthcare equity research at HSBC bank.

Eli Lilly saw the pitfalls that Novo had already encountered and was more prepared to evade them

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) placed semaglutide on its drug shortage list in 2022, allowing compounding pharmacies to legally sell their own formulations. Novo restricted the starter doses of Wegovy in 2023 as demand outstripped manufacturing, and problems arose with counterfeits.

Meanwhile, in 2022, Eli Lilly launched tirzepatide – initially for diabetes (as Mounjaro) and the following year as Zepbound for obesity. Tirzepatide also spent two years on the FDA’s official shortage list, but Lilly’s manufacturing investments ended that shortage several months before that of semaglutide. New prescriptions for Lilly’s Zepbound reportedly surged past Wegovy in the US this year. ‘Lilly had what I call second mover’s advantage,’ says Kumar: it saw the pitfalls that Novo had already encountered and was more prepared to evade them.

Unfortunately for Novo, after the official shortages ended, compounders have continued fighting to retain their rights to produce GLP-1 drugs. ‘Three million people in the US currently take these medications. Two million are on Lilly or Novo’s drugs. One million are on compounded versions,’ says Kumar.

US data on new prescriptions (those just starting treatment) favour Lilly’s tirzepatide 60:40 over Novo’s semaglutide medicines, Kumar says, which will erode Novo’s overall share. However, he adds that prescription data misses the fact that the vast majority of compounded drugs are semaglutide. Overall, many more people are taking semaglutide (just not the FDA-approved version). ‘Compounders tasted an opportunity and there was an influx of API from China and other parts of the world that are not regulated in the same way,’ he adds. Novo is fighting compounders in multiple lawsuits.

Transformation

Novo issued sales and profit warnings in July, and its share price was hammered, losing 20% or more in a single day. It had already surprised analysts by pushing out Lars Fruergaard Jørgensen as chief executive in May. ‘This was a complete shock,’ says Hanne Sindbæk, Danish author of two books on Novo Nordisk.

This is the largest job loss in Danish history. But if you compare it to the number [Novo] hired last year, it is not so dramatic

The company had prided itself on consistency. ‘When I spoke to the former [chief executive], he mentioned several times that Novo Nordisk is marked by continuity in terms of values, technologies and markets,’ says Martin Jes Iversen, a professor of innovation at Copenhagen Business School in Denmark. ‘Yet the reality is that Novo has faced a transformation.’ Novo had to move from insulin for diabetic patients to a consumer market for obesity treatments.

Lilly began selling Zepbound direct to consumers and packaged drugs in vials with syringes instead of more expensive prefilled pens. It took Novo more time to set up a direct line to consumers. ‘This was a completely new market,’ says Sindbæk. ‘Novo sold its medicine via doctors and hospitals and did not think of itself as selling to consumers.’

In August, Mike Doustdar was appointed the new chief executive. The job cuts he announced in September ‘sends out a very strong message about cost cutting,’ says Kumar. Around 5000 of the 9000 job cuts are expected in Denmark. ‘This is the largest job loss in Danish history,’ says Iversen, a setback for many families. ‘But if you compare it to the number of employees [Novo] hired last year, it is not so dramatic.’

Novo employed around 78,000 people at the end of August 2025, an 80% increase from just five years ago. ‘They had far too many employees. That’s what happens when you grow so quickly,’ says Sindbæk, who believes there was employee acceptance of the restructuring plan, partially because Doustdar has been at Novo for over 30 years. ‘This person knows the company and its culture,’ says Iversen. ‘I’d have been sceptical if it was someone from the outside.’

Change in strategy

Novo’s loss of market share means it now has more supply than demand, says Kumar. The bottleneck is convincing insurers and healthcare providers to pay. Despite assessments suggesting the drugs represent good value for money – particularly if additional benefits like lowering the risk of cardiovascular and other diseases are factored in, at current prices they are still too costly for healthcare systems to provide them to all potential patients. Novo will therefore be under pressure to drop its prices. Semaglutide is scheduled for US federal price negotiations in 2027 under a mechanism introduced by the Biden administration. Novo’s patents in various countries will also begin to expire from 2028, opening the drug to generic competition.

However, in terms of the drugs’ performance, Kumar is optimistic about Novo’s prospects. A head-to-head study (from Lilly) published earlier this year suggested tirzepatide was superior to semaglutide in reducing body weight and waist girth. However, Kumar points out that over 85% of trial patients took the highest dose of tirzepatide. ‘In the real world, only a third of patients are going to the highest dose.’

Both companies have follow-up drugs in their pipelines, exploring both oral and injectable treatments. ‘I disagree that Novo’s drug portfolio is materially worse than Lilly’s,’ says Kumar. ‘These are two fantastic companies that are ahead of the curve.’ He encountered transformed sentiments around drugs for treating obesity in June at the American Diabetes Association conference in Chicago, US. ‘Diet and exercise hasn’t worked. Pharmacotherapy we now know works,’ he says. ‘The medical community is convinced. The patients are convinced. The payers have to find a way to pay for it.’

Additional information

Editorial note: This story was updated on 29 September to clarify data around prescriptions of the various drugs concerned

No comments yet