As America seeks a new president, science hangs in the balance

When I set out to cover the US presidential election for Chemistry World, reporting on what’s at stake for America’s science enterprise, I approached the task like a scientist (and, of course, a journalist). I put my personal assumptions and biases aside, and became an impartial and unpartisan observer.

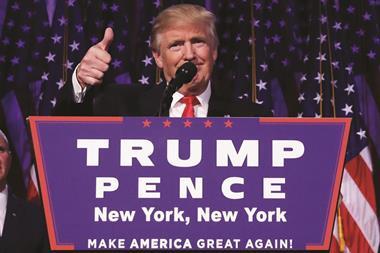

I called up and emailed dozens of people in the science policy world in search of the objective truth about what a President Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump might mean for America’s researchers and scientific competiveness. I talked to academic researchers, policy wonks, scientists who had served at the highest levels in both Republican and Democratic administrations, and a former Republican congressman who is a prominent research advocate. And with every call, my hopes of delivering a balance of viewpoints grew smaller, because although support for Clinton was by no means unanimous, when it comes to science few of them had anything good to say about Trump.

Weeks of research did yield some positive talk from the biotech sector, but it was lukewarm. Representatives of the chemical industry even favoured Clinton over Trump – slightly – unusual for an industry that usually leans towards the Republican candidate.

One of the only clear Trump accolades that turned up was from former Republican House speaker Newt Gingrich. He told the Biotechnology Industry Organization’s convention in June that Clinton is ‘extraordinarily knowledgeable’ about medical research, but Trump would be ‘more aggressive’ on issues like reforming the US Food and Drug Administration and promoting ‘decentralised, market-oriented proposals’ for encouraging innovation, according to STAT news.

It is clear that Trump’s statements and tweets from the campaign trail and before have earned him the reputation of being either ignorant– or contemptuous – of science. This goes beyond his repeated characterisations of climate change as a ‘hoax’.

For example, Trump appeared to lament the phase-out of ozone-depleting chemicals from hairspray when addressing West Virginia coal miners in May. ‘You know, you’re not allowed to use hair spray anymore because it affects the ozone. You know that, right?’ Trump asked amid laughter. He told the miners that the quality of hairspray has gone downhill since. ‘I said, “Wait a minute, so if I take hairspray and if I spray it in my apartment, which is all sealed, you’re telling me that affects the ozone layer?” “Yes.” I say, no way, folks. No way!’

Trump’s anti-science reputation was evident at the Republican convention in July, during a performance of the rock band Third Eye Blind. Singer Stephan Jenkins asked the audience: ‘Raise your hand if you believe in science,’ and was met with boos.

At the Democratic convention the following week, Clinton declared to applause: ‘I believe in science. I believe climate change is real.’

Beyond his science gaffes, Trump is also accused of promoting a brand of nationalism that’s already deterring foreigners from working or studying in scientific and technical fields in the US. This could have disastrous implications not only domestically, but also globally. The US educates thousands of immigrants every year who return home and help to build their countries’ own research base. If the flow of talented scientists to the US from around the world were to start drying up it is not only the US that would lose out, but the global scientific enterprise as a whole.

No comments yet