Election season sees a chemical industry unenthusiastic about either candidate, and a research community overwhelmingly backing the Democratic nominee

America is set to vote for a new president on 8 November, and the next occupant of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue will have to be able to address complex issues at the intersection of science and politics. As voting day nears, it is clear that the chemistry of this election is quite different from those of past years.

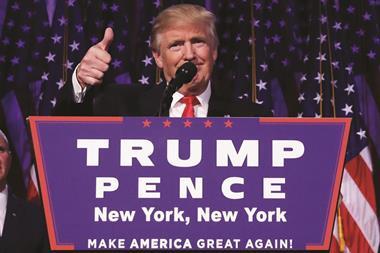

In recent history, the chemical industry has been pro-Republican come election time, but in the current face-off between Democrat Hillary Clinton and Republican challenger Donald Trump, the sector appears to favour Clinton, while the reverse may be true for the biotech industry. The academic and scientific communities, however, back Clinton overwhelmingly.

‘We are concerned about both candidates,’ states Larry Sloan, the outgoing president and chief executive of the Society of Chemical Manufacturers and Affiliates. Although Sloan says Trump would be more likely to revisit the ‘excessive regulations’ that have burdened the chemical industry under the Obama administration, he states that Clinton is more pro-trade and more inclined to revisit big global trade deals. Trump has repeatedly promised to withdraw from some of the US’s biggest global trade agreements.

Sloan also criticises the Republican candidate as ‘not very knowledgeable’ on the recent overhaul of the 40-year-old law Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) that regulates chemicals in America. This bipartisan achievement, endorsed by the chemical industry and some environmental organisations, was signed into law by President Obama in June. It gives the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) enhanced authority to require testing of new and existing chemicals.

Sloan and many other observers agree that the EPA desperately needed this new authority, but they say more money and staff are required. Trump’s repeated vow to dismantle, or at the very least severely curtail, the EPA doesn’t bode well for TSCA.

Two former chiefs of the EPA who served in Republican administrations have also spoken out against Trump and endorsed Clinton, saying that he has shown ‘a profound ignorance of science and of the public health issues embodied in our environmental laws’.

Raising budgets, stapling green cards

In Clinton’s response to 20 questions about science and technology and coordinated by ScienceDebate.org, Clinton vows: ‘Advancing science and technology will be among my highest priorities as president.’ She goes on to assert that the US is ‘underinvesting in research’.

Clinton’s technology and innovation plan, released in June, proposes increasing the research budgets of key US science agencies. She also wants to automatically grant permanent residency to foreign nationals who receive master’s or PhD degrees in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (Stem) from US institutions. That proposal would enable highly skilled Stem workers to circumvent the temporary H-1B guest worker visa process. Clinton also wants ‘start-up’ visas to allow top entrepreneurs from abroad to come to the US and establish businesses.

Advancing science and technology will be among my highest priorities as president

Hillary Clinton

By comparison, Trump wants to revamp the H-1B visa programme so that Americans are hired over cheaper foreign graduates. The Republican candidate is also calling for a lower corporate tax rate to encourage innovation, and slashing or eliminating spending on certain federal agencies and programmes, including the EPA and the Department of Education.

‘He has clearly demonstrated no interest in funding fundamental research,’ says Lawrence Krauss, a professor at Arizona State University’s school of earth and space exploration. ‘It is not clear to me he even understands what that is.’

Donna Nelson, an organic chemist and president of the American Chemical Society (ACS) who spoke with Chemistry World in a personal capacity, says that the positions the candidates take matter as the US is the global research powerhouse. Changes to US science policy reverberate around the world simply because the nation is the preeminent player in research. She adds that scientists need to reach out to both candidates and educate them on the value of peer reviewed research so that it can be used to develop policies on global challenges such as climate change, energy and medicine.

‘God knows’

‘What Hillary Clinton would do is to extend the Obama administration’s support for science and technology,’ says Michael Lubell, the director of public affairs at the American Physical Society. ‘In the case of Donald Trump, I would say “God knows”.’

We must make the commitment to invest in science, engineering, healthcare and other areas that make the lives of Americans better

Donald Trump

However, Trump does note in his response to ScienceDebate.org’s 20 questions that, despite increasing demands to curtail spending and balance the federal budget, ‘we must make the commitment to invest in science, engineering, healthcare and other areas that make the lives of Americans better, safer and more prosperous’.

Neal Lane, a physicist who served as science adviser to former president Bill Clinton and as director of the National Science Foundation before that, emphasises that Hillary Clinton has talked a lot during the campaign about the importance of investment in research and innovation in general. She has also discussed science education and workforce issues, as well as the necessity of having knowledgeable and skilled people emigrate to the US. By contrast he says Trump has not ‘said much of anything about the importance of research, anything positive about immigration and in many other ways has denigrated the importance of science to policymaking and to the country’.

Potholes take precedence

As an example of his last point, Lane cites remarks by Trump about investment in space science, technology and exploration. While campaigning in November, Trump said practical problems like potholes take precedence over space exploration. Trump also appeared to disparage the National Institutes of Health (NIH) – the nation’s well-respected biomedical research agency – on public radio last year. But what’s got Trump in most trouble with the scientific community is his questioning of climate change, calling it pseudoscience and even tweeting that ‘the concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese in order to make US manufacturing non-competitive’.

His policies, if implemented, would be a disaster – talented people from around the world would be denied entry

Lawrence Krauss, Arizona State University

In his response to the ScienceDebate.org questions, Trump says ‘there is still much to be investigated in the field of “climate change”’, and he suggests that ‘the best use of limited financial resources’ would be to focus on things such as ensuring access to clean water worldwide, new energy sources and tackling diseases like malaria.

Former Republican congressmen John Porter, who served as the long-time chair of the House of Representatives subcommittee that funds science agencies, backs Clinton for president and says Trump ‘has no knowledge of science or the value of research’. From a support-for-science perspective, Porter says he would be ‘very, very unhappy’ if Trump is elected president. By contrast, he describes Clinton as ‘very aware of the value of science’.

Nina Fedoroff, a molecular geneticist at Pennsylvania State University who served as the science and technology adviser to Hillary Clinton during the Obama administration, and Condoleeza Rice under Republican president George W Bush, echoes Porter. ‘She does understand the extent to which science drives our economy; Trump, not so much,’ says Fedoroff.

Immigration frustration

Fedoroff emphasises how hard it is for any foreign-born scientist to get through the US immigration system and obtain a green card, let alone become a citizen, and she notes that Clinton wants to ease that process. In contrast, Fedoroff calls Trump’s stance on immigration ‘a huge concern’. She notes that the nations he has identified as of concern from an immigration standpoint, like Iran and Pakistan, have ‘enormous talent pools’.

Krauss says that Trump is promoting xenophobia which is already stopping people coming to work and study in Stem in the US. ‘His policies, if implemented, would be a disaster – talented people from around the world would be denied entry,’ he states.

Clinton does understand the extent to which science drives our economy; Trump, not so much

Nina Fedoroff, Pennsylvania State University

It does not appear that Clinton has an official committee of 30 or so top-level scientists to advise her campaign, as Obama did when he was running for president, but it is apparent that she still has plenty of support. Lane and Nelson are among what is described as a slew of prominent scientists offering their counsel to the Clinton campaign.

Lane says there will be ‘a long line’ of researchers and engineers who will be interested in helping a Hillary Clinton administration. ‘On the Trump side, I just don’t know – that is a totally different community,’ he adds. ‘I don’t know who would be on such a list, I have not heard of anybody.’

One person who has been linked with advising the Trump campaign on science and technology issues, though, is Republican congressman Lamar Smith, who chairs the House of Representatives’ science, space and technology committee. Smith has been involved in a number of public feuds with the academic community in recent years, however, questioning the value of a number of research grants. Smith, who trained as a lawyer and is not a scientist, has also repeatedly questioned the science of climate change.

Contributions to Trump and Clinton from the chemical and related manufacturing sectors reflects a lack of enthusiasm for Trump, compared with previous Republican candidates. The Center for Responsive Politics found that Trump received only about $43,000 (£33,000) in donations from the chemical and related manufacturing industry, which is less than a third of what Clinton has received. The last Republican challenger for the presidency, Mitt Romney, received $360,000 from this sector.

Industry cautious

Meanwhile, the US biotechnology industry appears unhappy with both major candidates. The Biotechnology Innovation Organization is not endorsing anyone, but the organisation’s president, former Republican congressman Jim Greenwood, has warned that ‘the stakes for the biotech industry could not be any higher’ in this election.

Greenwood has described the biotech sector as ‘fragile and under growing pressure’, noting that ‘a lone tweet by a candidate for high office can have unintended market moving consequences’. Those remarks appeared to reference incidents like the one in September 2015 when Clinton sent a tweet accusing drug companies of ‘price gouging’. The Nasdaq Biotechnology Index fell by 4.7% following that remark.

More recently, Clinton – who wants to reverse the ban on Medicare drug price negotiation – sent a tweet last month saying there is ‘no justification’ for Mylan Pharmaceuticals’ recent price hikes for EpiPens, used to treat serious allergic reactions. She said the price of the EpiPens has increased by more than 400% in recent years.

John Castellani, the recently retired president and chief executive of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, argued when he led that organisation that Clinton’s plan to regulate prescription drug prices would ‘turn back the clock on medical innovation and halt progress against the diseases that patients fear most’. He said she is proposing ‘sweeping and far-reaching’ changes that would restrict patient access to medicines, lead to the loss of ‘countless jobs’, and erode the US’s standing as the world leader in biomedical innovation.

But Trump has attacked the biotech and pharmaceutical industries too, arguing that Medicare should be able to negotiate drug prices and import cheaper drugs from other countries.

Trump’s unpredictability problem

It is clear that Trump would work hard to cut taxes on corporations and slash regulations, which would appeal to the chemical industry and others. But Lane says it’s difficult for such sectors to support Trump because of the uncertainty surrounding the candidate and his positions.

Glenn Ruskin, who spent over a decade as a spokesman for the chemical industry before joining the ACS, agrees with Lane. ‘The one thing that industry thrives on is predictability,’ Ruskin says. He notes that Trump has repeatedly vowed to tear down the EPA regulatory regime but said nothing about what would replace it.

The Baker Institute for Public Policy at Rice University in Texas has just issued a report addressing how America’s next president should deal with science and technology policy. It urges the new commander-in-chief to select a top-notch scientist as an adviser before inauguration in January and develop a science, technology and innovation strategy within the first 100 days after taking office.

To help illustrate the importance of what is being recommended, retired Democratic congressman and physicist Rush Holt pointed out that former President Bush had no permanent science adviser in place when the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks occurred. He suggested that this was why the response to the subsequent anthrax attacks was poorly coordinated.

In contrast, Holt, the chief executive of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, noted that Obama had already appointed John Holdren as his science adviser when he was drafting the economic stimulus package to counter the ‘Great Recession’ that hit in 2008. The result, Holt said, was that when the stimulus was enacted in February 2009, it contained an extra $21.5 billion to support R&D.

Whoever becomes the next US president in January, experts warn they won’t be able to navigate the current geopolitical turbulence without first laying down a sufficient science policy infrastructure.

Correction: The article was updated on 29 September to alter a position attributed to a source

No comments yet