A call to fight plastic waste

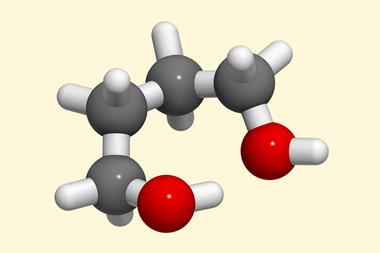

It’s almost impossible to imagine modern life without plastics. Inspired by the ancient use of naturally occurring polymers, 19th century chemists discovered polystyrene, PVC and polyethylene, among others. It wasn’t until 1907, however, that the first fully synthetic plastic was invented by Leo Baekeland – the eponymous Bakelite.

Over 100 years later, plastics are ubiquitous in almost every area of our lives. And while these materials are of indisputable value, enabling the production of cheaper and more effective goods that have enhanced standards of living for many, the negative environmental impacts are difficult to quantify.

The solution to our ‘plastics problem’, much like the origin, will likely lie with chemists. But perhaps, in addition to designing more environmentally friendly solutions, we also need to seek help from citizen scientists and crowdsourced chemists.

Environmental measures

When a sperm whale washed up on a Scottish beach in November last year, the synthetic contents of its stomach caused shockwaves. One hundred kilograms of plastic ropes, shopping bags, cups and other rubbish was found balled up inside the animal. Tragically, reports of similar discoveries are becoming more routine. An estimated five trillion pieces of plastic have ended up at sea – with an additional 12 million metric tons added each year.

A 2016 review highlighted an array of citizen science projects that have been contributing to our understanding of microplastics in the ocean. This shows the power of citizen science to gather data and help understand issues that can’t be achieved through traditional research methods.

Some projects involve beach monitoring – a methodology thought to have originated over 35 years ago – whereby citizens are assembled to comb beaches and remove plastic waste, which can then be analysed by researchers. More recently, mobile applications have enabled citizens to contribute photographs of plastic debris on beaches or in the ocean. This provides information about date, time, packaging and the extent of the pollution.

Translating essential environmental action, such as beach clean-ups, into citizen science requires careful design and planning to ensure reproducible procedures that can be easily followed by contributors. Additionally, partnerships with analytical laboratories can offer valuable insights into issues such as the pollutants leached from ocean plastics, the levels of microplastics found in marine organisms and the impact of plastics on the microbe colonies in and around those organisms.

Coupling activism with citizen science is a powerful tool to stimulate an appreciation of science in members of the public who might not engage with the subject through more traditional channels. It’s also important to emphasise the potential of citizen science to contribute to research output. For example, over 11.5 million people have participated in the Ocean Conservancy’s International Coastal Cleanup project since it was founded in 1986. In addition to removing 100 million kilograms of debris from coasts around the world, the project has generated data that has been used in 85 reports and papers.

Digesting the problem

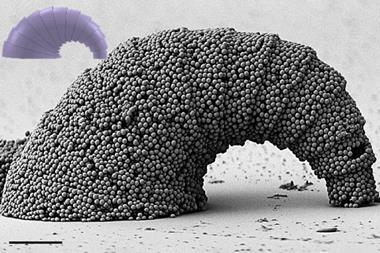

Citizen science could also help us to understand how to design and express bacteria that can eat plastic waste. In 2016, Japanese researchers reported that a bacterium discovered in piles of discarded plastic can degrade one of the most widely used plastics, PET. Further modifications to Ideonella sakaiensis, the aforementioned polymer-guzzling bacterial species, are required if it is ever to come close to being commercially viable. But what other microorganisms might nature have evolved to help us clear up our unnatural disaster? Recruiting citizen scientists to take samples on different plastic waste sites might speed up our understanding.

Reducing plastic waste begins at ‘home’

Even as we consider how to reduce our own plastic footprint, crowdsourcing can help. Much of the machinery found in chemistry laboratories is encased in plastics. From vacuum pumps to micropipettes, we’re surrounded by the stuff. But perhaps the most worrying contribution to plastic pollution by our community is in the form of the more fleeting members of our research groups: disposable syringes, vial lids and gloves.

Our colleagues in biosciences have already taken this inventory. In a letter to Nature in 2015, researchers from the University of Exeter, UK, estimated the amount of plastic waste generated by the 280 research scientists in just one of their departments over the course of a year. Their towering figure of 267 tonnes was extrapolated to similar institutions around the world, leading to an estimated 5.5 million tonnes of lab plastic waste, the equivalent mass of 67 cruise liners.

If we are willing to follow our bioscience colleagues and share our dirty plastic laundry in public, perhaps we could crowdsource figures for chemistry’s contribution to this cruise liner-scale catastrophe. Together, we could find ways to minimise single-use plastics alongside our efforts to swap to greener solvents and chemical processes.

The plastics problem

How chemistry is providing solutions to the issue of plastic waste

No comments yet