How well are companies that produce and use plastics living up to their duty?

In the 2017 documentary series Blue Planet II, naturalist David Attenborough issues the world a stark challenge. ‘Industrial pollution and the discarding of plastic waste must be tackled for the sake of all life in the ocean,’ he says. In directing our attention to the plastic problem, the series focused close attention on companies originating the materials. There is no denying that plastic brings valuable benefits, like keeping food edible for longer. Yet waste is clearly a flaw that it appears producers and users had previously failed to take adequate responsibility for. Blue Planet II has seemingly started an industry transformation, as companies strive to show they are now living up to that responsibility.

Tom Zoete from environmental organisation Recycling Netwerk in Utrecht, the Netherlands, argues that corporate responsibility’s importance often hasn’t been stressed enough. Instead Zoete suggests industry often deflects responsibility onto individuals. ‘As a consumer, it’s very hard to avoid all this single-use plastic packaging,’ he says. By contrast, if a company reduces the weight of its product by a few grams, tonnes of material might never reach the market. ‘That’s enormous,’ Zoete says. ‘Compared to that, each individual consumer’s choice has a very limited scope.’

Now, companies are recognising the waste problem in many ways. For example, investment management firm Circulate Capital from New York, US, has raised $106 million (£84 million) from PepsiCo, Procter & Gamble, Dow, Danone, Unilever, Coca-Cola and Chevron Phillips Chemical. It will use the money to invest in recycling enterprises in Asia. Rob Kaplan, Circulate’s founder and chief executive says that such companies are jointly recognising their responsibilities. ‘Each of our founding investors has bought into a “rising tide lifts all boats” investment strategy,’ he says. ‘They recognise that the end of life of their products or packaging is part of the plastic pollution problem, and they want to be part of the solution. They also recognise that the solutions are bigger than any individual company and we will only be able to execute them if we collaborate.’

There are many such schemes where companies are banding together to rise to Attenborough’s challenge. The largest is the Alliance to End Plastic Waste (AEPW), which launched in January 2019 to fund ‘education and engagement’, waste collection and recycling infrastructure, plastic clean-up and innovation. It now includes 47 companies, who have contributed $1 billion of a total $1.5 billion target. But estimates suggest that plastic worth up to 10 times as much is discarded as waste each year after its first use. Nevertheless, even seemingly small commitments from producers and users of plastics and packaging may yet trigger their transformation to newly responsible members of society. And in case that happens too slowly, some governments are already intervening.

Less conversation, more conversion

Kaplan recognises that ‘it will take much more than the $100 million we are investing to solve the ocean plastic problem’. Circulate therefore wants to attract institutional investors ‘who are currently sitting on the sidelines’ to join in the work. ‘Every investment must reduce plastic pollution and also demonstrate that investing in waste, recycling, and the circular economy can generate attractive financial returns,’ says Kaplan. ‘Our vision is to develop a circular economy whereby we can take old plastics and turn them into a new, reusable resource for future materials.’ As such, investor companies hope that they will be able to use and benefit from resources generated by the recycling firms they will fund, Kaplan adds.

German chemical giant BASF provides one example of how that might work in its collaboration with Quantafuel of Oslo, Norway. Together they are commissioning a plant capable of pyrolysing and purifying 16,000 tonnes/year of plastic waste to produce hydrocarbon raw materials in Skive, Denmark. BASF is investigating various options for supplying its integrated Verbund production sites with greater volumes of pyrolysis oil, says Christian Lach, chemcycling project lead. ‘It is unlikely that there will be only one solution to the large issue of chemical recycling, and we intend to drive this topic in whichever way we can.’ For more on different approaches to chemical recycling see p22)

Like Kaplan, Lach describes a sense of collective responsibility. ‘BASF is collaborating with companies from throughout its value chain, with [non-government organisations], governments, multilateral institutions and others about ways to combine efforts for greater impact,’ he says. These include the associations’ projects on waste management and education, like those under the Marine Litter Solutions programme and the World Plastics Council. ‘Furthermore, BASF engages in the Ellen MacArthur Foundation “Circular Economy 100” initiative and supports Operation Clean Sweep, an international program that strives to prevent plastic pellet, flake and powder loss into the environment which may occur during production, transport, converting and recycling.’

Consumer goods giant Unilever is also a core partner of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. By 2025 it intends to halve its use of virgin plastic, through a combination of reducing its overall use of plastic packaging by more than 100,000 tonnes, and accelerating its use of recycled plastic. It says that it will also help collect and process more plastic packaging than it sells.

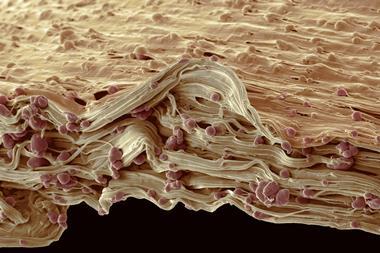

‘These plans demand a fundamental rethink in our approach to our packaging and products,’ explains Louis Lindenberg, Unilever’s Global Packaging Sustainability Director. ‘Last year in the UK, Unilever pioneered the development of a new detectable black pigment for our high density polyethylene (HDPE) bottles, which we use for our Tresemmé and Lynx/Axe brands, so they can now be seen by recycling plant scanners and sorted for recycling.’ Normally automatic optical sorting machines are unable to distinguish black plastic because they use near infrared light, which is absorbed by the carbon black pigment, he adds.

Lindenberg also notes that in 2019 Unilever partnered with Saudi Arabian petrochemical giant Sabic to use a new recycling technology to incorporate recycled plastic into ice-cream tubs. In the same year Unilever partnered with material specialist Notpla from London, UK, to test condiment sachets made of seaweed.

Zoete, however, is sceptical of how effective such schemes can be. ‘When they’re announced there’s lot of marketing,’ he says. ‘But in the next few years, there’s no independent follow-up to verify that all these benefits really are realised.’ Overall, such schemes tend to delay laws that might achieve more, he argues. He highlights Recycling Netwerk’s own research into the activities of AEPW members. It found that several companies were each investing over a billion dollars in plants to produce new, non-recycled plastic. That’s similar to the amount the 47 companies together had committed to fight ocean waste. ‘There was a strong contradiction in the claim that they were trying to reduce the impact of plastic pollution,’ Zoete says. ‘Most people expect growth in plastic production in the coming years.’ Chemistry World sought comment from the AEPW on this issue but received no response.

One reason for these large investments is that US shale gas production has made virgin plastic cheaper. Meanwhile, increasing commitments to use recycled plastics such as recycled polyethylene terephthalate (rPET) are increasing their price. ‘So, you get into rather strange situation where more very important beverage producers like Coca Cola, Unilever or Nestlé are aiming to increase the amount of rPET used in the packaging, but there will be some kind of shortage,’ Zoete says. This may add to companies’ interest in Circulate’s scheme and others like it, which could increase production of such materials for them to use.

Kaplan believes that large investments in new production and commitments to reduce plastic waste ‘are not mutually exclusive’. He argues that to secure capital from institutional investors and get the billions needed to finance Asia’s future infrastructure requires ‘evidence-based track records’. He adds that Circulate’s investments will be focused on south and southeast Asian countries because they leak the most plastic waste. ‘Ocean Conservancy estimates that a 45% reduction of plastic leakage is possible by improving waste management and recycling in just China, Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines,’ he says.

Forced into responsibility

These Asian countries also currently lack extended producer responsibility (EPR) laws that elsewhere compel manufacturers to tackle waste arising from the products they made. While such laws originated in Sweden in the 1970s, today the most prominent example is Europe’s Single Use Plastic Directive, adopted in May 2019. ‘Governments can really oblige companies to take the environment into account, whether it be through EPR schemes, or making them pay for the pollution that that has been caused by their products,’ Zoete says.

BASF tracks such regulatory developments closely, Lach notes. ‘We have established global standards and have set ourselves targets which go significantly beyond legal requirements,’ he says. To reflect EPR, BASF strives to sell its products in reusable packaging, Lach adds. For example in Germany, BASF has been taking back packaging that cannot be reused since the early 1990s. ‘As a chemical company, we not only support improving the management of the post-industrial/pre-consumer waste but also post-consumer waste. Thus, we have been actively involved in the development of different EPR schemes for different sectors.’

Higher production capacity does not necessarily mean more plastic waste pollution, BASF also argues. ‘To tackle pollution caused by plastic waste, combined efforts by different stakeholders focusing on establishing a well-functioning waste management infrastructure with proper collection and recovery, as well as awareness raising are key,’ Lach says.

The EU’s Single Use Plastic Directive is also now inspiring national and state-level legislation in the US, explains Susan Collins, president of the Container Recycling Institute (CRI) based in Culver City, California. CRI is a strong advocate of container deposit laws, in particular where people are rewarded for returning bottles or cans. ‘Container deposit laws excel in three separate areas,’ Collins explains. ‘They produce very high quantities of material, they produce high quality material that is suitable for use in new bottle and can manufacturing, and they cut beverage container litter in half, on average.’ She notes that whereas previously a good year would see just two or three US states consider introducing such laws, in 2019 nine states did.

Zoete stresses the role that such schemes have on how people think, for example what happens when EPR makes companies responsible for cleaning up their products. ‘You will think twice before designing packaging that is very prone to be thrown away in the environment,’ he says. ‘Today taxpayers are paying all the costs for cleaning up that end of life product. It will be more fair and balanced when the producing companies are implicated as well. But this is an interesting instrument because it will make the choice in the design phase very clear as to which type of package they will use. Today, we have a whole lot of products designed to be thrown away and then we wonder why they’re thrown away.’

However the plastics industry transforms itself to spare the oceans from waste, Circulate’s Kaplan is confident that it’s possible. ‘Ocean plastic is one of the most pressing environmental issues of our times but one that can be solved,’ he says. ‘150 million tons of plastic are today in the ocean and 8 million tons are added each year, which is the equivalent to a garbage truck of plastic being added each minute. But when we take a step back, 8 million tons is manageable. Singapore manages 8 million tons of waste per year.’

The plastics problem

How chemistry is providing solutions to the issue of plastic waste

- 1

- 2

- 3

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Taking responsibility for waste

- 5

- 6

- 7

No comments yet