US and European regulatory agencies are leading worldwide collaborations to ensure drugs from outside their borders are safe

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has published plans to ensure that American citizens continue to enjoy access to safe drugs, even as the regulatory pressures of globalisation grow. The FDA’s Global Engagement Report outlines a transformation that will change it from a domestic public health agency to a global one. The plan includes building coalitions of local regulators into a robust worldwide product safety net. This will help deliver wider active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) production monitoring to satisfy the demand for good quality, value-for-money drugs in developed countries. But these measures have been met with warnings that they could hamper growth in the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) industry and make it more difficult for developing countries to get access to safe drugs.

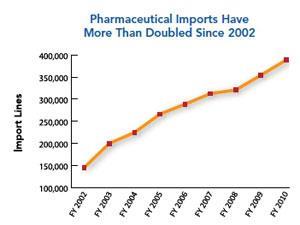

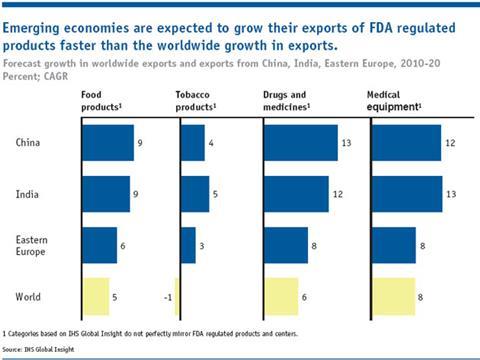

The job of international surveillance has grown significantly following a fundamental shift in API manufacturing to Asia, particularly China and India. The FDA has estimated that from 2005-2011 imports of pharmaceutical products to the US have doubled. It has also predicted that India and China’s local pharmaceutical production value in 2012 will be two and a half times what it was in 2006. China already has the largest number of FDA-registered drug manufacturing establishments outside the US, followed by India. ‘India has emerged as the largest producer of several drugs, such as ethambutol, ranitidine and the sulfonamides,’ Dilip Shah, secretary-general of the Indian Pharmaceutical Alliance, tells Chemistry World. ‘It is producing APIs and intermediates not only for the generic industry but also for the brand name industry for products under patent protection for more than a decade.’

While such countries offer low cost products, western drug regulators like the FDA are keen to ensure that this doesn’t come at the cost of non-conformance with API Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP). ‘APIs worldwide are regulated using the harmonised standard known as ICH Q7,’ explains FDA spokesperson Sarah Clark-Lynn. ‘However, some countries treat APIs as just another industrial chemical. Even in countries that recognise ICH Q7 there are significant differences in whether or how API sites are inspected, which can lead to problems in the regulation of APIs shipped and used internationally. The quality of an API determines in part the safety and efficacy of the finished drug upon which consumers depend. As with other components, the global manufacturing and regulatory communities need to be vigilant.’

To gain entry to US or EU markets, foreign manufacturers’ facilities must currently first be inspected and approved by the FDA or the European Medicines Agency (EMA), respectively. As drug production shifts to Asia, the task for regulators grows, says David Cockburn, head of manufacturing and quality compliance at the EMA. ‘Whether it’s APIs or finished product it is more difficult in terms of time and ease of access for EU regulators to supervise manufacturing activities in geographically distant locations to the same degree as domestic manufacturing,’ he says. ‘Therefore there is more emphasis on the importer fulfilling obligations and, to a varying extent, on local regulatory controls and collaboration with other international regulatory partners. The ultimate aim must be for local authorities to be able to supervise local activities against internationally agreed standards.’

Building regulations

Universally trustworthy local regulation is some way off, notes Frederick Abbott, an expert in international law and pharmaceutical policy and regulation at Florida State University, US. ‘The problem at the moment is that India and China historically have not invested heavily in domestic regulatory capacity and need to focus for the time being on improving in that arena,’ he says. ‘In this regard, the EMA and FDA first need to work with the Indian and Chinese governments on improving domestic regulatory capacity. Only then will genuine co-operative relationships be feasible in the sense of reliance. There is no doubt that India and China are graduating enough students with technical expertise that will be required to staff operations. It is a matter of committing the resources to build up the domestic agencies.’

The inspection burden currently still falls on developed countries and the FDA is rising to this challenge. ‘FDA is increasing inspections of foreign manufacturing sites and working with global organisations like the Pharmaceutical Inspection Cooperation Scheme to develop rigorous inspection standards for API sites,’ Clark-Lynn explains. ‘We have established 13 foreign posts in 10 countries, including India and China, in order to improve global drug quality.’ But even with those resources in place, partnering with other countries is still an essential part of the US agency’s plan, she says. ‘FDA can’t be everywhere all of the time and we depend on robust regulatory systems in source countries to inspect API sites.’

Wherever a plant producing drugs authorised for the European and US markets is located in the world, it is already regulated by the EMA and FDA respectively, both Cockburn and Clark-Lynn emphasise. However, teamwork between regions allows more regular inspections and provides knowledge of facilities regulated in one region but yet to be authorised in another. The FDA and EMA have consequently been collaborating in recent years, sharing plant inspection reports and seeking to better understand each other’s inspection practices. ‘With growing international collaboration in this area, I believe the proportion of sites that are of interest to more than one region and that have been inspected is probably much higher than is generally perceived,’ Cockburn says.

Harmful side-effects

Shah says that the FDA is already regulating more than 200 plants in India. ‘Its system of inspection of document trails and stringent penalties for failures act as a major deterrent to non-compliance,’ he adds. But the cost of regulation is passed onto the patient, undermining savings developed countries receive from manufacturing in Asia. That impact will be biggest for small volume and low value drugs and will make it hard for smaller companies to compete.

Cockburn says that inappropriate emphasis can be put on the cost of compliance. ‘GMP compliance linked to quality assurance and risk management principles are about public health protection,’ he points out. ‘However, it also promotes good business practice through getting things right first time, reducing quality variability thereby improving efficiency and maintaining business reputation.’

However, Abbott underlines that non-GMP compliant companies are well positioned to take business from those who are. ‘It is expensive to build plants and to hire the personnel necessary to maintain high regulatory standards,’ he says. ‘Among the major Indian API manufacturers, there is a commitment to invest in quality and the companies seem able to absorb the expenses and compete in the global marketplace. Yet, Chinese API producers appear to be undercutting Indian prices.’

Shah also suggests that, while complying with quality and GMP standards is technically achievable, some developed world regulations are in fact ‘non-tariff barriers’ to API imports. He points to the EU’s June 2011 Falsified Medicines Directive and the FDA’s collection of ‘user fees’ from drug producers to speed approval processes as examples. Shah says that if the developed world wants to lower healthcare expenditure, it should use its collaborations to simplify regulatory monitoring processes. ‘This would encourage, instead of discouraging, entry of newer players and thereby promote competitive forces to reduce the cost of medicines,’ he says.

Meanwhile, Abbott notes that most countries don’t have agencies like the EMA and FDA to enforce standards overseas. ‘As a consequence of this bifurcated international regulatory structure, formulators - and therefore patients - in countries with less external regulatory capacity face greater risks,’ he says. ‘From my discussions with formulators and API producers in developing countries, this is a significant problem.’

Andy Extance

No comments yet