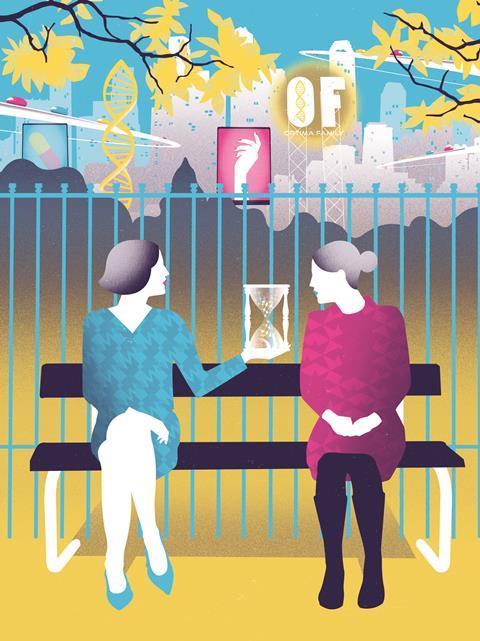

What if the price of eternal youth is more than people can pay? Robert Reed looks at a beautiful – but worrying – future

Two women sit in a public park. Both look like 50-year-old ladies, except neither one of them is.

One woman wears long gloves. Mentioning the lovely bright day, she peels them off to show her hands. The right hand looks much younger than 50, smooth and strong. In contrast, its mate isn’t only spotted and thoroughly wrinkled, but every joint is badly swollen by what appears to be arthritis.

But there’s no arthritis in the world. Not any more, there shouldn’t be.

The second woman remembers arthritis. She remembers being 50, but that feels like a lifetime ago. ‘You look miserable,’ she says, grimacing.

‘It can be, yes.’

‘I don’t understand.’

‘Why I do this?’ The younger woman opens and closes the stiff fingers. ‘To prove a point to my clients. With a glance, they’ll see the absolute control that I have over every portion of my body.’

The older woman looks away.

Her companion just turned 26, but a mature face gives the youngster respectability, which in turn helps her make a very good living. When she wants, she has a warm, patient manner. Like now. ‘I wish I could sit here all day,’ she says. ‘I do. But I seem to have more work than I have time. Odd as that sounds.’

Staring at the sky, her companion says, ‘I suppose you see an upturn whenever a celebrity has a major birthday.’

‘It’s been noticed, yes.’

‘Well, my favorite actress turned 100. Just last week, wasn’t it?’

The girl allows herself a surreptitious smile. ‘I know the lady. By the way.’

The woman turns back, looking at the girl again. ‘Is that so?’

‘We’re not friends or anything. But I was still working at “the shop” when she was given a tour. And I was able to shake her hand.’

‘The shop?’

The girl names a multi-world pharmaceutical combine. ‘Of course “shop” is a silly word. The facility is huge. Even our little corner was overwhelming. 40 researchers, 1000 lab techs. All robots – the lab techs, not the researchers.’

Why should good health be locked inside a cage, nobody but the rich getting the keys?

The women smile at each other.

‘You don’t work there now?’

‘No, I quit,’ the girl says, every word emphatic. ‘I quit when I realised that I couldn’t keep working for a company like that.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because I wanted to help people, and I wasn’t helping people. Deep genetic analysis and epigenetic maps – that was my job. Which, I know, sounds terribly complicated.’

‘Baffling,’ her companion agrees.

‘Except these aren’t new technologies. Not really. We’ve been able to do this work for years. But you know what keeps it expensive? Multiply those researchers by 20 programmes, in 30 locations – and that’s just the sectors I know about. Then how many other “shops” are there? You must see the adverts – they fill the schedules nowadays.’

The old woman straightens her back, and her chin juts out.

‘Except why? That’s what I asked myself. Why should good health be locked inside a cage, nobody but the rich getting the keys?’ The girl can be quite passionate when she delivers this speech. That’s because she enjoys this as much as any part of her job. ‘A lot of innocent people have to die. And quite honestly, that is just wrong.’

Her companion sighs. ‘Oh, I know,’ she says. ‘I’ve lost good friends. And my third husband too.’

The girl knows the woman’s biography. But it’s best to nod and pretend ignorance, waiting for the other person to ask a criminal’s question.

A new smile surfaces. Brave in one sense, wicked in another. Looking square at the girl, she asks, ‘What can you do for me?’

‘That depends entirely on what you want, madam.’

In crisp detail and with a surprising amount of technical expertise, the old woman describes her medical history. She happens to be the same age as the famous actress, and in most ways, her body enjoys respectable health. But mutations have struck her cardiac muscles. Each mutation is already uncommon, and the resulting cluster is what gives her a unique, one-of-a-kind disease. That detritus diminishes her heart’s output, and with time, her condition will lead to sudden cardiac events.

The girl interrupts. ‘Most insurance policies would pay for treatments.’

‘I don’t want treatments,’ she says. ‘I want to be healthy again.’

‘You’re hoping for a full rebirth. Is that it?’

‘A partial rebirth. Of my heart only.’

The moment demands a quick look around the quiet park. As if anyone cares what two middle-aged ladies are saying. ‘And you found me how?’

‘My granddaughter. I asked her for advice, and she knows a man whose sister works for your former employer – and somehow that news got to you…’

I can’t use the resources on someone like you

The girl shrugs. ‘As I mentioned, madam. These are busy days for me. And I don’t have as many resources as I would like.’

‘Official avenues are too expensive for me. But I intend to pay you for your time and trouble.’

‘That’s always appreciated. But to do any work, I’ll need to have a suitable facility. I’d have to define these mutations, synthesise new genetics, and then build the viruses to bring them where they need to be. Every step has costs. And maybe you haven’t noticed, but there have been some rather public arrests made lately.’ The girl rubs the old hand, those swollen aching joints. But they don’t ache. The arthritic bulging is induced using a cocktail that her healthy modern liver will chew up in another hour. It’s a fine liver, and the girl is a fine liar. But she tells the truth when she says, ‘I don’t help people who can’t reach a certain threshold. I’m sorry to be blunt, but I did a background check on you. And you might live for years without any problem. So you see? To be blunt, I can’t use the resources on someone like you.’

The woman shifts her weight against the chair. ‘My granddaughter can help.’

‘No, she’s deep in debt because of a divorce settlement,’ the girl says. ‘And her father and all of your ex-husbands are dead too.’

There. She shoves the old lady into a very difficult place, and now she’ll wait for the tears.

But the old gal is too proud for that. Instead, she hits the bench’s wooden slats with a fist, shouting, ‘You’re wasting my time, you bitch.’

The girl stands, looking ready to leave.

But with the first step, she pauses. She puts on a face that looks injured, and then shamed. Quietly, she says, ‘Wait.’

Wiping her eyes, the 100-year-old woman stares at her last hope.

‘Wait,’ the girl repeats. ‘There is one possibility.’

‘What?’

She sits. ‘But listen carefully, all right?’

Robert Reed is a science-fiction writer based in Nebraska, US

The age of eternity

What if the price of eternal youth is more than people can pay? Robert Reed looks at a beautiful future

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

The age of eternity

- 2

- 3

No comments yet