After recent restructuring and job losses at big pharma companies, many are collaborating with smaller companies and universities to get research done.

There’s little doubt that in the past century the pharmaceutical industry has played a pivotal role in improving the lives of millions of patients all over the world. Indeed, one dreads to think what a world we would live in without the initiatives of pharmaceutical scientists and researchers. Through the discovery and development of novel therapeutics, such as Lipitor (atorvastatin), Gleevac (imatinib) and Plavix (clopidogrel), the industry changed the shape of the world’s medical management and truly brought healthcare into the scientific age.

These achievements didn’t come without rewards – the industry has earned untold billions from its blockbuster drugs. But drug development isn’t cheap: only two out of every 10 drugs brought to market generate enough revenue to cover the cost of their development. And so a vast deal of this income is reinvested in the expensive and time-consuming endeavour of discovering the next life-saving medications. It is this financial advantage in R&D that provided the starkest contrast between the pharmaceutical industry and the other drug discovering sector: academia.

Legislation

For most of the 20th century, universities were stuck with little financial incentive and technological capability to match the pharmaceutical giants. Instead, the vast majority of academic research was funded by federal research grants, and if any new entities were developed, federal law prevented exclusive licensing deals. That was the case until 1980.

The Bayh–Dole act, also known as the Patent and Trademark Law Amendment Act, changed everything. Responding to the USA’s economic malaise of the 1970s, the US Congress passed the act to permit any university, small business or non-profit institution to negotiate exclusive licenses for potential new therapeutic agents developed in their labs – even if the research was federally funded. Of course, compared to pharmaceutical companies, universities were still underequipped and so were unlikely to become a viable competitor. But that was never the idea. The true value of the Bayh–Dole act lay in its potential for moving academic discoveries into the commercial landscape via exclusive licensing deals.

While ostensibly alike in their training and methods, the worlds of academia and the pharmaceutical industry couldn’t be more different

But this would take time. After all, while ostensibly alike in their training and methods, the worlds of academia and the pharmaceutical industry couldn’t be more different. For a start, their ideals and benchmarks for success are poles apart. In the world of the pharmaceutical industry, the highest honour for a researcher is to develop a new chemical or biological entity that can be taken to human trials; while in academia, the whole focus of a researcher’s career can be to successfully publish their work. With the added hurdles of different infrastructures and responsibilities to their investors, the challenge of getting these two sectors to successfully collaborate seemed impossible.

In spite of these difficulties, 12 academic drug discovery centres had been established in the US by 2001, climbing past 100 by 2013. So what happened? How did the pharmaceutical industry and academia learn to share?

Mergers and acquisitions

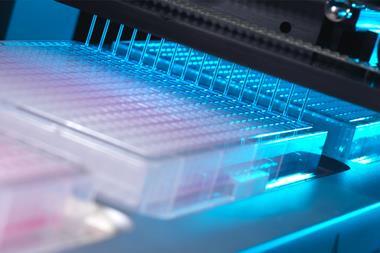

By 1996 the pharmaceutical industry had reached its 20th century peak. The FDA had approved a record 59 new molecular entities, and exciting new technologies such as high throughput screening and genome sequencing looked like they could carry the industry for decades to come. But then things changed, and the lofty goals the sector had set itself began to seem more far off than they had imagined.

One such change was the rise of mergers and acquisitions. While the casual onlooker to the sector might assume these business transitions to be pretty regular and innocuous, they can be anything but. When a pharmaceutical executive looks to buy another’s pipeline, a pharmaceutical researcher can often look for another job. From 2000 to 2009, 1324 mergers and acquisitions occurred, and 300,000 pharmaceutical jobs were lost. These measures often appeal to the companies’ shareholders, but the long-term impact on the ever-needed new molecular entities (NMEs) is questionable. One analysis of 10 large drug companies showed that acquisitions actually resulted in a 70% decrease in NME output.

And that was just one issue. While the problems of mergers and rising R&D costs troubled the pharmaceutical industry during the late 1990s and 2000s, they only led to a small rise in new academic drug discovery centres. The major challenge that led to the US having over 100 centres by 2013 was a lot more problematic. Starting in 2010, a number of blockbuster drugs (defined as one that makes about $4 billion a year [£2.9 billion]) suddenly hit their legal expiry dates and lost their patent protection. Over the next two years this so-called ‘patent-cliff’ led to $68 billion being lost in worldwide sales because of the rise of generic competition; and even conservative estimates have predicted a $290 billion loss from 2012 to 2018.

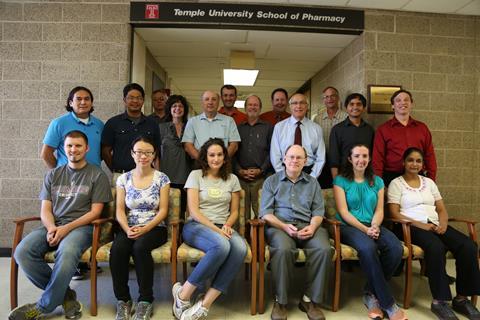

Together, these factors forced the pharmaceutical industry to undertake significant structural changes. And change can be a good thing. Before long, a new appreciation for the benefits and expertise found in universities began to enter the sector. And now we live in a world where leading centres, like the Moulder Center for Drug Discovery Research at Temple University School of Pharmacy in Philadelphia, US, can work with both independent research institutes and biotech companies to great success.

It turns out, not only is there a life after pharma, but it’s a good life

Magid Abou-Gharbia, director of the Moulder Center

As one of the few centres to use high-throughput pharmaceutical profiling, the Moulder Center has far higher chances of identifying successful drug candidates that could one day go to market. Thanks to this kind of technology and others like it, their researchers’ projects in the areas of cancer, multiple drug resistance and hepatitis B infections have all led to grants, publications and exciting new patents.

Thanks to these successes and subsequent investments, centres like Moulder can now act as a source of novel science that bolsters the pharmaceutical industry’s search for novel therapies that could change patients’ lives. And that’s beside the benefits of allowing academic scientists the opportunity to move their research into the commercial realm.

‘Many of us thought that our professional lives ended when we left pharma,’ says Magid Abou-Gharbia, associate dean and director of the Moulder Center. ‘It turns out, not only is there a life after pharma, but it’s a good life. Things have changed and now people can pursue their career in a different way and continue doing the science they love.’

All in all, the relationship between pharmaceutical companies and academia has come a long way. Not long ago, many university researchers would leer at their peers who were bold enough to partner with commercial organisations. Now, after the seismic shifts of the world healthcare sector, the very same academics and their universities are earning the benefits of pharmaceutical collaborations. After all, academic freedom is important, but it is industry that brings drugs to the patients.

No comments yet