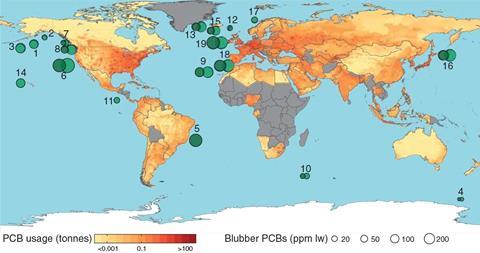

The survival of over half of the world’s killer whales hangs in the balance because of a highly persistent and toxic class of chemicals. Despite a near total ban on the production of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) 30 years ago these carcinogenic and reproductive toxins continue to persist in the environment.

New research modelling the effects of PCBs on these top marine predators over the next 100 years has revealed that many populations are likely to go into decline – and some may even collapse completely in certain areas.1

‘Killer whales can take up these compounds but their metabolic system isn’t ideally suited to getting rid of them,’ explains lead author Jean-Pierre Desforges of the Arctic Research Centre in Aarhus University, Denmark. ‘Because [PCBs] are not broken down in the environment very fast they tend to just accumulate in these animals over their entire lifetime.’

PCBs are organochlorine compounds that were first manufactured commercially in 1929, and subsequently used in a range of products throughout the 20th century including electrical equipment, carbonless copy paper and pigments and dyes. Once the environmental hazards and carcinogenic nature of PCBs were recognised, they were banned across the US in 1979 with other bans brought in around the world.

Today, however, PCBs still persist around the globe, even in remote areas far from where they were made. This is because these chemicals are resistant to most forms of degradation, have a long half-life and poor solubility in water that lets them circulate freely in the world’s oceans. It’s estimated that few countries will meet their targets to stop using and properly dispose of PCB-containing equipment in the next 10 years under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants.2

The persistence of PCBs and the extent of the contamination of the world’s oceans is what has led to their accumulation in so many killer whales, in what Bert van Bavel from the Norwegian Institute for Water Research describes as an ‘optimum cocktail’. As killer whales are at the top of the food chain, they are among the world’s most PCB-contaminated animals as a result of feeding on contaminated fish and marine mammals. Their fatty blubber is also well-suited to binding the chemical, concentrating PCB levels further.

‘It’s one of the first of few long-term assessments of the risk of PCBs,’ notes van Bavel, who wasn’t involved in this work. ‘These are rough estimates and future scenarios are much less certain… but it points us in the direction of what we should do legislation-wise.’

Desforges and his collaborators predict that populations of killer whales around industrial areas that once manufactured large quantities of PCBs, including the UK, Japan and Brazil, might go extinct. ‘The levels of PCBs are so high in these populations that we suspect there’s wide-scale reproductive failure,’ Desforges says. ‘As the older animals die out there won’t be any new life to replace them… And there’s likely to be significant immune suppression which leads to these individuals being more at risk of dying from disease.’ He adds that these two factors are responsible for the majority of PCBs’ toxicity in killer whales. ‘What we’re hoping to show in this study is this problem still hasn’t gone away and we still need to do more.’

References

1 J Desforges et al, Science, 2018, DOI: 10.1126/science.aat1953

2 S Smith and P Jepson, Mar. Policy, 2017, DOI: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.06.033

No comments yet