Journal editor tells chemists to get tough on bad practices such as scrubbing spectra of embarrassing impurities

Data integrity in the chemical sciences is under the spotlight. In a broadside aimed at shoddy data practices, the editor of Organic Letters, Amos Smith, has called on chemists to put their house in order and root out poor practice. But with the focus now on this murky issue the question remains just how widespread manipulation of raw data actually is in the chemical sciences?

Smith declined to be interviewed by Chemistry World but in his editorial1 he explains that his journal has hired an analyst to scrutinise supplementary data more closely. As a result a number of instances have been discovered where raw data, such as spectra, have been ‘cleaned up’, in some cases to remove evidence of impurities. Such bad behaviour is, fortunately, still rare Smith says. However, he adds that such acts are ‘unacceptable’ and that ‘manipulation of research data casts doubts on the overall integrity and validity of the work reported’.

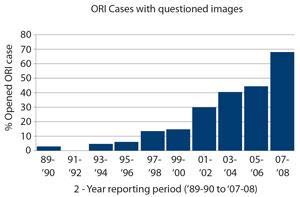

It is extremely difficult to get a handle on how the big the problem of data manipulation in the scientific literature actually is. The US Office of Research Integrity, which polices the country’s science community, has seen a steady increase in instances of manipulation of images (see figure), although the number still remains small. However, it is difficult to determine whether this rise is a result of better detection or the ease with which it is now possible to alter data.

What’s in an image?

In the experience of Mike Rossner, who was editor of the Rockefeller University Press’s Journal of Cell Biology for nine years, instances of data manipulation have remained ‘remarkably consistent’ over the past decade. Journal of Cell Biology has been an early pioneer of image checking after Rossner discovered a suspect figure back in 2002. Since checks were introduced 11 years ago, he says that the rate of data manipulation – whether outright fraud or cleaning up an in image in an unacceptable manner – has stuck at around 1% of accepted papers.

PIs are the first line of defence and their first weapon of defence is education

Rossner says that the process of checking manuscripts at his former journal is deceptively simple – modulating the contrast and brightness of the image to highlight tell-tale signs of manipulation. As a result of their policy a number of journals beat a path to Rossner’s door from the biomedical sciences, including Science, particularly after the Hwang Woo-suk cloning debacle in 2005, which also encompassed an instance of image manipulation. Now, publications such as Science check all accepted publications for manipulation, while others, like Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences or the Nature research journals, do spot checks on a few manuscripts per issue.

It seems that the chemistry community is coming to this problem later than some other fields. Many chemistry journals are still relying on editors to spot any problems and aren’t employing the skills of a data analyst or some of the simpler techniques that can uncover image manipulation.

Truth is beauty

‘Scientists must be absolutely honest. This is the heart of science,’ says Ryoji Noyori, president of RIKEN and 2001 chemistry Nobel laureate. ‘Manipulation of experimental data is totally unacceptable, even if it does not affect the scientific conclusion.’ Noyori, who is also chairman of the editorial board at Advanced Synthesis & Catalysis, has joined the conversation on ethical conduct in the chemical sciences on a number2 of occasions.3 As to why this is happening, he worries that a ‘flood of mediocre researchers’ driven by the need to build their publication list is debasing the scientific literature.

Arturo Casadevall, one of the authors of a landmark paper that revealed that most retractions were the result of fraud, rather than simple mistakes,4 says that ‘science is under more pressure than ever from a variety of factors (internal and external) and that these pressures could be driving practices that are questionable’. These pressures include the ‘publish or perish’ culture, the winner takes all nature of science and vicious competition for a select few research jobs.

Beyond the issue of the manipulation of data this debate has opened up another can of worms – the responsibility of principal investigators (PI) to instil strong ethical values in their students. In his editorial, Smith says that the team leader must create an atmosphere where any result can be presented without fear, so there is no temptation to embellish data. Noyori agrees. ‘This wrongdoing, either ethical or technical, results largely from the lack of suitable mentorship,’ he says. ‘The first mentor, like parents in a private family, is the most influential.’

So what is the solution to this problem? Rossner says that the ‘PIs are the first line of defence and their first weapon of defence is education. Something they can do proactively is examine all figures for all papers coming out of the lab very carefully before submission.’ He adds that this shouldn’t be seen as mistrust, but as a learning experience for students and postdocs, who may be unaware of what is acceptable or otherwise when presenting data. Casadevall adds that the problem is still under the radar of most scientists and the profile of this issue urgently needs to be raised. ‘Before a consensus emerges on how to address a problem there has to be a consensus that there is a problem.’

References

1 A B Smith, Org. Lett., 2013, DOI: 10.1021/ol401445g

2 R Noyori, Angew. Chem, Int. Ed., 2012, 52, 79 (DOI: 10.1002/anie.201205537)

3 R Noyori and J P Richmond, Adv. Synth. Catal., 2013, 355, 3 (DOI: 10.1002/adsc.201201128)

4 F C Fang, R G Steen and A Casadevall, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2012, 109, 17028 (DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1212247109)

No comments yet