Exposure poses potential risks for pregnant women working in retail

Women of reproductive age could be exposing themselves to harm by working on retail cosmetics and perfume counters. Researchers found higher levels of phthalates in these workers in Taiwan and warn that this can pose health risks, particularly for pregnant women.

Phthalates are a class of compound added to plastics to introduce flexibility and put in cosmetics as carriers for fragrances. Several phthalates have been listed as endocrine disruptors and attention has focused on their potential cumulative effects on reproductive health.

A team from Taiwan assessed levels of phthalates in 23 cosmetics, four perfume and nine clothing sales assistants before and after their shift. ‘We found that the potential reproductive and [liver] risk of these [cosmetics and perfume] sales clerks for a period of time were increased, and exposure route from inhalation and dermal absorption could be crucial,’ says first author Po-Chun Huang at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences in Taiwan.

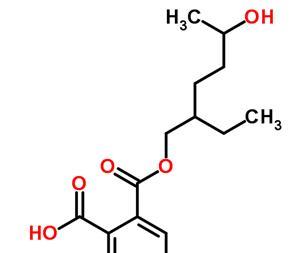

The main contributors to exposure were dibutyl phthalate (DBP), diethyl phthalate (DEP) and di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP). Higher levels of DEP and DEHP were measured in cosmetics and perfume sales areas of the shop. And cosmetic sales staff had higher levels of urinary metabolites of DEHP, DEP and DBP than those selling clothing. The formulations in cosmetics and fragrances sold in Asia may differ from those sold elsewhere, however, even for the same brands. It is therefore uncertain if the results of the Taiwanese study are applicable worldwide.

Significant increases in phthalates were found in cosmetics sales staff after their shifts. ‘The daily [exposure doses] of DEHP in 63% of our perfume clerks and 50% of our cosmetic sales clerks exceeded the reference dose set by the US Environmental Protection Agency,’ the authors note.

‘A lot of the concern about phthalates is that they could interfere with testosterone production, particularly during the prenatal period when they can have subtle feminisation effects [on a male foetus],’ explains Tracey Woodruff, director of the programme on reproductive health and the environment at the University of California, San Francisco. ‘Biomonitoring shows women have higher levels of phthalates.’ This may indicate cosmetics and personal care products are an important sources of exposure.

Woodruff points to a recent finding of a 50% decline in sperm concentration in men and notes that phthalates as a class of chemical are implicated. Phthalate exposure may act cumulatively, so risks rise if you are exposed to more than one, she adds.

Most of the cosmetics and perfume sales staff who took part in the study were of childbearing age and continued to work while pregnant. ‘We suggest indoor air quality of phthalates should be re-evaluated, and reproductive-age women should work in other departments to reduce the risk, especially for those pregnant workers,’ says Huang. Woodruff suggests reformulation of cosmetics would be a better approach.

DEP is the most commonly used phthalate in cosmetics worldwide and does not pose risks for human health as currently used in cosmetics and fragrances, according to the US Food and Drug Administration. Woodruff is not so sure, however, as ‘recent epidemiological studies are questioning whether DEP might pose a risk’. Some phthalates have been banned from cosmetics in the EU, including DBP and DEHP.

References

1 P-C Huang et al, Environ. Pollut., 2017, DOI: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.10.079

No comments yet