AbbVie and Samsung Bioepis resolve patent litigation over arthritis drug Humira

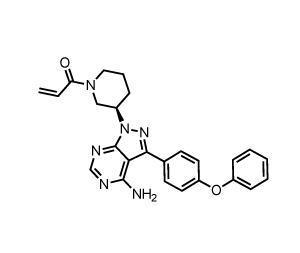

AbbVie has settled a legal case with biosimilars company Samsung Bioepis over Imraldi, the South Korean company’s proposed version of AbbVie’s blockbuster TNF inhibitor Humira (adalimumab). Bioepis will receive a non-exclusive license allowing it to sell the biosimilar in the US from June 2023. In the EU, where the patent expires sooner, the licence period will begin this coming October.

Last September, AbbVie settled a similar case with Amgen, and its Humira biosimilar, Amjevita, can be sold in the US from January 2023. Both companies will have to pay royalties to AbbVie. All remaining litigation between the parties – including that in Europe with Bioepis’ partner there, Biogen – will be dismissed.

AbbVie’s general counsel Laura Schumacher claims that the settlement reflects the ‘strength and breadth’ of AbbVie’s intellectual property. ‘We continue to believe biosimilars will play an important role in our healthcare system, but we also believe it is important to protect our investment in innovation,’ she said. ‘This agreement accomplishes both objectives.’

Several other companies are also developing Humira biosimilars, and as the patents expire so much earlier in Europe the development process is already well advanced. With annual global sales topping $14 billion, Humira is currently the world’s biggest selling drug, and thus it is unsurprising that it is attracting so much attention.

Just a few days after the Bioepis settlement, Mylan announced it is partnering with Japanese company Fujifilm Kyowa Kirin Biologics to license and commercialise a biosimilar in Europe. Other litigation is already under way, according to Joshua Whitehill, a New York-based associate at law firm Goodwin. This includes a case with Boehringer Ingelheim over its Humira biosimilar Cyltezo.

‘Some biosimilars companies have said in public statements they could be on the US market a lot earlier than 2023,’ Whitehill says. ‘Momenta has said it could be on the market in the next couple of years. I wouldn’t be surprised to see more settlements for these litigations. But usually they are litigated very hard.’

Both Abjevita and Imraldi are expected to launch in Europe this coming October, according to GlobalData senior analyst Alexandra Annis. ‘We anticipate Humira will face strong biosimilar erosion in the European markets following the success of biosimilars of Remicade and Enbrel across the EU,’ she says. ‘Biosimilars provide a cost effective option for patients, marking a 10% to 35% discount to the annual cost of therapy of their branded counterparts.’

Pay-for-delay

The US market for biosimilars is several years behind Europe, but with FDA finally approving a path to market a couple of years ago, there is now a lot of activity. The AbbVie/Bioepis case represents the third major settlement in biosimilar litigation. The first was Genentech’s deal with Mylan over its breast cancer drug Herceptin (trastuzumab).

Pay-for-delay has been a big issue for generic drugs, but we will see for biologics

The IP situation for biologics is generally more complex than it is for small molecules. ‘AbbVie and Genentech both have rather large patent estates around their biologics, much larger than you typically see for [small molecule] drugs,’ Whitehill says. ‘A lot of these are follow-on patents that go out into the 2030s. There is a historical view that these patents are weaker, and they are usually narrower than the original patent.’

While settling litigation means giving up potential revenue, it does give certainty over when their products will face competition, Whitehill says. ‘If the biosimilars catch on and get prescribed, it will affect their bottom line,’ he says. ‘Companies are trying to be realistic, get ahead of it and not have to guess what is going to happen. There is a lot of value in having a date.’

It remains to be seen whether settlements like this will fall foul of the authorities; in small molecule generics, pay-for-delay deals, where the originator company pays a generic rival to abandon its patent litigation to delay competition, have been challenged in court. ‘I haven’t heard anything yet that would make me think US government would frown upon it here,’ Whitehill says. ‘Pay-for-delay has been a big issue for generic drugs, but we will see for biologics.’

Humira is not the only big-selling biologic currently facing US patent disputes – Amgen’s Enbrel (etanercept) is also under siege. A trial is imminent that will determine whether Sandoz can launch the biosimilar Erelzi, with the Swiss company disputing two Amgen patents that are not due to expire until the late 2020s.

‘Following the Humira patent settlements, GlobalData anticipates a similar outcome for Sandoz, and all other companies developing biosimilars of Enbrel,’ GlobalData’s Annis says. This would delay the launch of all etanercept biosimilars in the US until at least 2028, she says.

Anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies already face biosimilar competition in the US, with Johnson & Johnson’s Remicade (infliximab) now sharing the market with Pfizer’s Inflectra and Renflexis from Merck. Annis expects it will be some time before peak sales of these biosimilars is reached. ‘[This is because of] US physicians’ initial reluctance to prescribe biosimilars for rheumatoid arthritis patients who are already stable on the branded product,’ she says.

No comments yet