Permits to emit carbon dioxide are a minor concern for fossil-fuel reliant manufacturers, including chemicals – so far

There is no evidence that Europe’s emissions trading scheme (ETS) has driven production of goods reliant on fossil fuels, like chemicals, elsewhere. That’s according to a report written for the European commission to look at relocation of such manufacturing driven by the ETS – a phenomenon known as ‘carbon leakage’. Report author and research and consultancy firm Ecorys, based in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, found other factors were more important in affecting where chemicals are made.

‘Changes in market demand, feedstock and energy prices play a much stronger role,’ Jip Lenstra, at Ecorys, tells Chemistry World. ‘Complex or expensive transport and production integration are also relevant factors.’ And while the latest ETS stage risks more carbon leakage, Lenstra thinks these other considerations will remain more important.

Carbon leakage, where fossil-fuel intensive manufacturing moves where greenhouse gas emissions are treated more leniently, is both an economic and environmental concern. Consequently, Ecorys’ report notes, when the EU launched its ETS in 2005 it allocated most facilities free allowances covering more emissions than have actually been produced to avoid this happening. As the 11,000 power stations and manufacturing plants covered by the scheme traded allowances the glut drove the cost of carbon down from €30/tonne (£25) to €3/tonne.

The resulting low price limited the ETS’s direct impact on manufacturers; however, power companies passed most of their extra costs on to them. ‘Those, according to industry, were quite a relevant factor,’ Ecorys writes. ‘Production with existing plants will continue, but new investments are expected to shift to regions with low energy costs.’ However, such investment shifts fall outside the commission’s definition of carbon leakage, it adds.

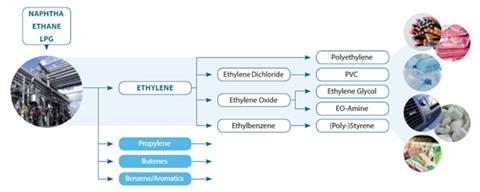

Other than moving manufacturing sites production shifts come through increased imports, although chemical substances’ hazards mean that many cannot be transported easily. Their production is also highly integrated, for example, with refineries often taking chemicals through several steps at the same site, limiting imports’ opportunity to intervene. Though most European imports remain steady or slightly lower one key exception is monoethylene glycol (MEG), a precursor for polyethylene terephthalate, which is commonly used in plastic bottles. Net MEG imports to Europe in 2012 were 40% higher than in 2002. But while this situation may involve some carbon leakage, ETS costs are likely not the key driving force. Instead, because MEG is easy to transport, it is an attractive use of ethane in Middle Eastern countries whose natural gas is otherwise hard to export.

Opportunity or burden?

Glen Peters from the Center for International Climate and Environmental Research, Norway, agrees that climate policy-driven carbon leakage has been very limited. ‘The net cost of the ETS to industry was likely to be very low and well within standard fluctuations in the costs of inputs,’ he says.

While this may mean some short-term pain, those industries that can adapt now will have a greater competitive advantage

Peter Botschek, director of energy at Cefic, the European Chemical Industry Council, says the report’s findings are unsurprising, as its objectives are ‘rather narrow’. ‘Our companies look into the future because investments are made for 20–30 years, a completely different perspective,’ he says. Over that period, demand for emission rights will exceed supply, raising prices. With the ETS now in its third phase, the EU is trying to speed up this process by delaying allowances’ release, or even retiring some altogether, steps Botschek calls premature. ‘In Europe 95% of manufacturing depends on chemical industry products,’ he says. ‘We could lose these building blocks through lack of access to competitive energy and feedstocks and a carbon price not matched outside Europe.’

But it’s difficult to separate the role climate policy plays in production and investment decisions, points out Julia Reinaud, from the Institute for Industrial Productivity. Looking only from this angle maintains the negative image that Europe is acting while other countries are not, and could be an oversimplification, she explains. ‘A number of elements influence companies’ decisions on production levels and investment: carbon policy is only one part.’

Ecorys’ report says that high carbon prices in Europe alone will make global competition slightly harder for European industry. Though Lenstra says his company hasn’t investigated the level at which carbon leakage might happen more noticeably, it assumes other drivers would still influence the location of chemical production more. ‘Easy-to-transport intermediate substances could be more affected,’ he says. ‘But overall only at a carbon cost above €50 for the chemical industry do we expect a significant impact from the ETS on its own. Of course, that could also make other effects, like energy costs, stronger.’

Peters notes that though carbon pricing today isn’t global, it’s likely that coverage and prices will increase. ‘The EU chemical industry is being given an opportunity to adapt early,’ he says. ‘While this may mean some short-term pain, those industries that can adapt now will have a greater competitive advantage in the near future. Emissions trading should be seen as an opportunity to spur innovation, not a burden.’

No comments yet