Researchers have recorded the first ever nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra of unmodified, off-the-shelf button batteries as they are charged and discharged. The metal battery casing had so far prevented such studies as it blocks the NMR radiofrequency field. But a team from Sandia National Laboratories, US, has found a way around this – simply turn the battery by 90°.

Since its discovery in 1946, NMR spectroscopy has allowed chemists to determine molecular structures, study molecular dynamics and characterise materials. As a non-destructive technique, it is also ideal to find out what is happening inside batteries as they operate. But batteries usually sit inside a metal casing that is impenetrable to the radiofrequency pulses responsible for exciting and detecting NMR active nuclei. Studies needed to be done on plastic-encased or otherwise specially modified batteries.

Now, a team of researchers has discovered that NMR studies on commercial lithium-ion button cells – whose metal casing consists of two halves separated by a non-metallic gasket – are in fact possible. The key is to flip them sideways so that their cylindrical symmetry axis sits perpendicular to the radiofrequency field. That way, only the metal along the battery’s thin edges is in the way of the radiofrequency field, which can still penetrate the battery’s inside.

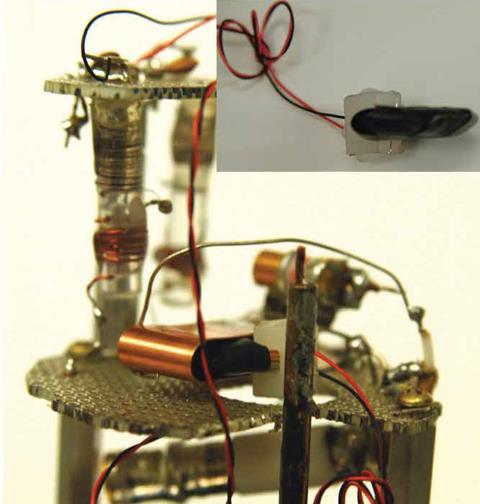

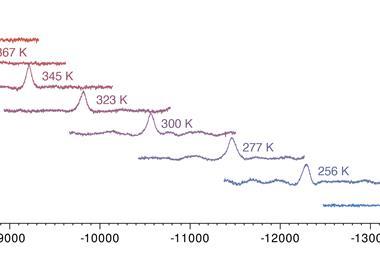

The researchers stuck different button batteries, wrapped in tape to prevent electrical contact, inside a hairpin coil (a strip of copper bent into a U shape) that was then loaded into an NMR machine. Connecting cables to the battery allowed them to charge and discharge the battery while recording lithium and fluorine NMR spectra – the first time an off-the-shelf battery’s operation has been studied this way.

The lithium spectra showed distinct signals for lithium–aluminium on the anode, lithiated manganese dioxide on the cathode as well as, surprisingly, a small amount of electrochemically dead elemental lithium – probably left over from the fabrication process.

While the method is compatible with button, pouch and prismatic cells, the team notes that it is unlikely to work for long cylindrical batteries that are entirely enclosed in metal and don’t have a non-metal gasket.

References

B J Walder et al, Sci. Adv., 2021, 7, eabg8298 (DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abg8298)

No comments yet