A gel coating that keeps solar panels cool using only water vapour from air has been developed by researchers in Saudi Arabia. The material boosts photovoltaic electricity generation by up to 19% without consuming energy.1

Less than 25% of the solar energy absorbed by commercial panels is converted into electricity. The rest is turned into heat, which increases the devices’ temperature and reduces their efficiency. Although water or air can be used to actively cool the panels, these methods involve complicated designs and require power to run. Passive technologies based on processes such as heat radiation are affordable alternatives, but their cooling power is low.

A team around Peng Wang at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Saudi Arabia, and the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, China, has developed solar panels that use hydrogels to keep cool. ‘With our design, we could effectively increase the electricity generation of a photovoltaic panel by 13 to 19%,’ says Wang. ‘This was possible because we could lower the panel’s temperature by at least 10°C.’

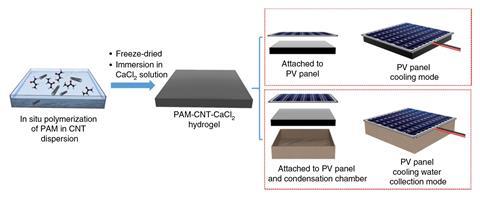

The researchers combined a commercial solar panel with a hydrogel-based material consisting of a polyacrylamide–carbon nanotube substrate and calcium chloride, a powerful water vapour sorbent.2 The gel is attached to the back of the panel where it can capture and store water from air during the evening and at night. In the daytime, when the sun warms up the panel, heat is transferred to the cooling layer and the trapped water evaporates, reducing the device’s temperature. Since the gel sticks to the panels through strong hydrogen bonds, it could be retrofitted to existing solar farms.

The scientists tested their system both in the laboratory and under real conditions. ‘The performance remained almost the same after a week and the gel regenerated on a daily basis,’ Wang says. But he points out that longer studies are required. ‘If the current material can’t last for at least two years, we’ll have to work on another one.’

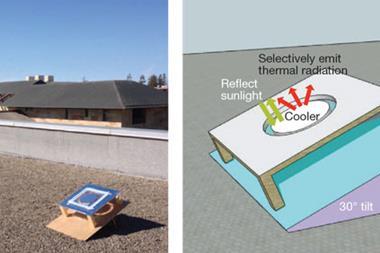

Aaswath Raman of the University of California, Los Angeles, US, who designed an air conditioning system that needs no power source, calls the approach ingenious. He says that the main advantages are that the cooling system is both passive and effective. ‘With many large-scale photovoltaic facilities operating in sunny and hot desert environments, this approach could have a real impact on the power output of a large plant.’

Norasikin Ahmad Ludin, a solar cell expert at the National University of Malaysia, adds that the material can extract and store large amounts of water even at a low relative humidity. ‘The water evaporated from the system can also be reused as fresh water and for cleaning the solar panel,’ she says.

But it’s important to determine the system’s cost-effectiveness, points out Raman. ‘This has to do both with its nominal cooling capability as well as its expected lifetime and any degradation one might expect to see after years of outdoor use.’

Wang is optimistic: ‘The material we are talking about is cheap and the price can be further reduced.’ He also notes that since the gel is stuck on the backside of the panel it could be combined with other strategies, such as coatings, to further enhance overall performance.

References

1 R Li et al, Nat. Sustain., 2020, DOI: 10.1038/s41893-020-0535-4

2 R Li et al, Environ. Sci. Technol., 2018, 52, 11367 (DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.8b02852)

No comments yet