Scientists have developed a computational method that quantifies and generates 3D maps of steric effects. The technique is more accurate than existing approaches and tests show it works across a wide range of cases, including atropoisomerism, coordination chemistry and organocatalysis enantioselectivity.

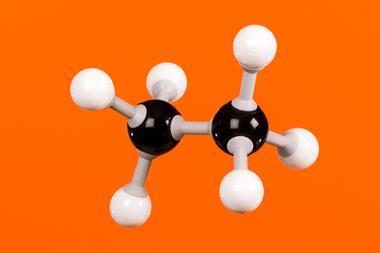

Steric effects are non-bonding interactions that can influence both reaction outcomes and molecular structures. Hindrance or blocking is the most commonly encountered steric effect and occurs when trying to force two atoms to occupy the same space. However, analysing and visualising steric effects remains difficult, and despite their ubiquity and importance they are often described only qualitatively, without explicit spatial or quantitative detail.

Now, Éric Hénon, from the University of Reims Champagne–Ardenne, and co-workers across France have developed a new method that can quantify and visualise steric effects directly from quantum calculations.

Called the Steric exclusion localisation function (Self), the method is based on the Pauli exclusion principle, a quantum effect that forbids two electrons with the same spin from occupying the same space. ‘This exclusion constraint has a cost: extra kinetic energy,’ explains Hénon. Self calculates that extra kinetic energy, which is closely correlated to steric effects.

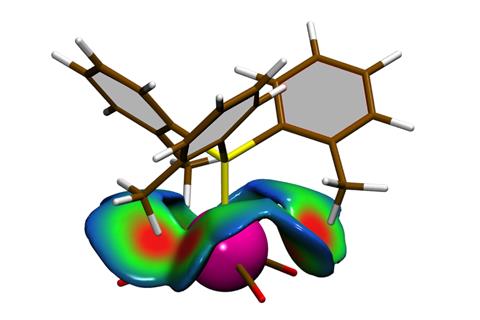

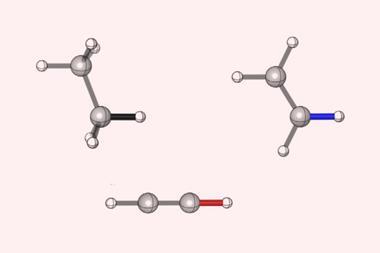

The method can produce 3D maps showing exactly where steric interactions play a role: ‘Being based on real quantum-mechanics calculations, rather than just measuring geometric distances between approaching molecules, is crucial. Our approach captures subtle effects that simple geometry misses, like the fact that repulsion isn’t the same in all directions around an atom,’ says Hénon.

Robert Paton, a computational organic chemist at Colorado State University in the US, says this method ‘moves towards a more correct picture of sterics … it distinguishes itself as instead of just giving you an energy value, they create a steric map.’

Indeed, a number of methods exist to probe steric effects, including energy‑based quantum‑mechanical methods and geometrical and classical methods, but they each have limitations. Energy decomposition analysis and symmetry-adapted perturbation theory can quantify Pauli repulsion but are often imprecise in showing where exactly the steric interaction is taking place, and which atoms are involved. And geometrical methods, although simple, tend to treat atoms like hard spheres with fixed sizes, failing to provide a realistic picture.

‘There are many different approaches to quantifying steric effects, most of which are socialised by showing that they correlate with other descriptors already in use,’ comments Natalie Fey, whose work at the University of Bristol in the UK involves computational studies of synthetically relevant organometallic catalysts. ‘However, the application to such diverse problems – organocatalysis, atropoisomerism – and comparison with Tolman parameters (incidentally well-known to be flawed and somewhat cumbersome to determine) with sensible results is interesting; easy visualisation is always useful, too.’

Hénon’s team tested Self on classical examples where steric interactions are often invoked to explain different outcomes. For example, they examined an organocatalysis reaction in which selectivity towards one product had been attributed to steric clashes between a mesityl group in the catalyst and a p-methoxyphenyl moiety in the reaction substrate. Self confirmed this hypothesis and also revealed additional, less obvious steric interactions.

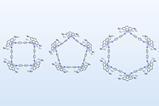

Another system the team tested Self on was a set of Ni–phosphine complexes, where steric interactions often limit the accessibility of the phosphine ligand’s lone pair. The researchers found that their results correlated well with the traditional method to study this – Tolman’s angles – but also showed that the interaction between the nickel centre and the ligand is smaller than Tolman analysis suggests.

These insights could prove useful for chemists. As Paton notes, ‘you could imagine comparing many different ligands in a library with this tool and using it to, for example, characterise or understand performance, maybe even ligand design… ultimately, that will allow us to think about how we might design better and more efficient systems and reactions.’

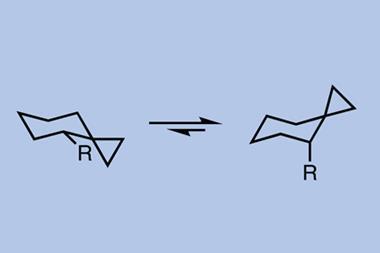

Hénon highlights that Self also works inside molecules, not just between them. ‘Previous methods were designed for two separate molecules approaching each other. But what about rotation barriers within a single molecule. That’s intramolecular steric repulsion, and Self handles it naturally. Other methods struggle badly with this. This opens new perspectives.’

Fey, however, is cautious about the future impact of the work: ‘Time will tell – for now, it’s promising because of its theoretical rigour and easy visualisation, but Tolman parameters, for example, are incredibly well-established for organometallic catalysis, so it might take a while to see whether this truly adds value.’

Additional information

The code for Self is available here: http://igmplot.univ-reims.fr

No comments yet