Chemists are constantly uncovering new materials, medicines and stunning new insights into the chemical processes that underpin the world we live in. 2025 has been no different, and the Chemistry World team has been kept busy as we try to keep readers updated with the most interesting and important discoveries across the chemical sciences. Over the last year, we’ve reported on more than 300 new papers that intrigued and amazed us. While it’s not possible to go back over every single one of them, here’s a summary of some of this year’s research highlights.

Chemistry in space

Understanding the chemistry on worlds beyond our own planet holds the potential to answer some of the biggest questions about the origins of life, the universe and everything. And in 2025 some spectacular experiments offered fascinating new insights.

In January, researchers shared results from the Osiris-Rex mission, in which a probe was sent to the asteroid Bennu, drilled a sample and returned it to Earth seven years later. The precious cargo revealed that the asteroid is rich in carbon, nitrogen and ammonia. More exciting was that the sample contained more than 30 different amino acids – including 14 of the 20 that make up proteins produced here on Earth – and all five of the nucleobases found in RNA and DNA. Bennu’s amino acids are both left- and right-handed – unlike the homochiral versions found in Earth-bound biology.

2025 also provided new results from the Mars rover missions. One study that cross-referenced measurements taken by the Curiosity, Pathfinder and Opportunity rovers, revealed that ferrihydrite – in addition to haematite – helps to give the planet its distinctive red hue. Because ferrihydrite forms in cool water, the findings suggest that water persisted on Mars’ surface for longer than previously believed.

The presence of liquid water on Mars many millions of years ago would have required warmer temperatures, likely driven by large amounts of carbon dioxide in the planet’s atmosphere. But that begs the question: where did all the carbon dioxide go? In April, Curiosity detected high concentrations of carbonates in the form of high-purity siderite minerals in Mars’ Gale crater – a suspected dried up lake. The findings provide evidence of an unbalanced ancient carbon cycle, in which carbon was sequestered into lake sediments.

Other astrochemistry highlights included a rationale produced by theoretical chemists that explains why highly unsaturated organic molecules are so abundant in the interstellar medium, and the discovery of cyanocoronene in the Taurus cloud – making it the largest fully aromatic molecule ever found in space. Meanwhile, astronauts on the International Space Station carried out the first ever fermentation in space, producing a miso paste that was much richer in esters and pyrazines than control samples made back on Earth.

Digging into history

Chemical analysis of material retrieved from sites of historical interest never fails to intrigue. In February this year, researchers found a unique organic glass inside a skull at the ancient Roman town of Herculaneum. Experiments suggested that the 79AD volcanic eruption heated the unlucky victim’s brain to temperatures above 510°C before it rapidly cooled. Microscopy studies of the glassy material revealed well-preserved neural structures. It’s the first known example of high-temperature vitrification of an animal tissue.

Analysis of artefacts recovered from iron age graves in southern Poland revealed that several jewellery items were made using an iron alloy from the same meteorite. The material, which contained an unusually high proportion of nickel, fell to Earth more than 2500 years ago.

Researchers in the US recreated recipes for several shades of the Egyptian Blue pigment that was hallmark of ancient Egyptian civilisation. The main colouring agent is cuprorivaite, a form of copper calcium silicate, while some versions incorporate different amounts of sodium carbonate, which gives a greener hue. The work could help conservation scientists to identify methods used to decorate ancient artefacts, and possibly guide them if they attempt repairs.

In Romania, researchers discovered the earliest known evidence of human-induced heavy metal pollution in a wild animal. The abnormally high levels of lead in the teeth of a brown bear, which died 1000 years ago after falling down a cave shaft, were likely caused by early mining and smelting practices in the local area. Meanwhile, metal pollution detected in a bore hole in North Yorkshire revealed that metal production in northern England continued long after the Roman period , challenging the long-held view that the area experienced economic collapse upon the end of Roman rule.

AI probes proteins’ secrets

Last year’s chemistry Nobel prize was awarded to researchers using AI to study proteins in entirely new ways, and in 2025 researchers have continued to reveal new secrets about proteins using powerful computer models.

In February, US researchers used a machine learning model called ProtGPS to identify a hidden pattern in proteins’ amino acid sequences that appears to determine whether they’ll become incorporated into biomolecular condensates that are involved in numerous cell processes. The developers of another AI system, called InstaNovo, claim that their creation could revolutionise protein sequencing in a manner akin to the way AlphaFold transformed protein structure prediction. While InstaNovo is still at an early stage, the system circumvents one of the major limitations of current sequencing approaches by interpreting peptide sequences direct from peptide fragmentation spectra.

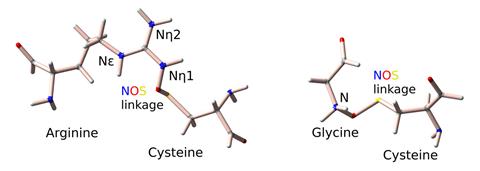

In June, another machine-learning model analysed 86,000 protein structures and uncovered dozens of previously unknown nitrogen–oxygen–sulfur linkages. The researchers behind the work hope that mapping these unreported bonds could lead to new medical treatments and could improve AI protein models. ‘If a bond is missing from the data, no matter how intelligent the AI is, it can never predict it,’ Sophia Bazzi, who led the work at Georg-August University Göttingen in Germany, noted at the time.

Meanwhile, a machine-learning tool developed by researchers in China was shown to be able to predict the stereoselectivity and activity of engineered enzymes by analysing their amino acid sequence. The team hopes that the tool can dramatically reduce the amount of work required to develop biocatalysts.

Detecting pollution

In 2025, chemists continued to highlight the many ways in which humans are changing the natural world. In February, UK-based researchers reported that flea treatments applied to pets are contaminating the nests of wild songbirds , causing harm to eggs and chicks. All 103 nests examined contained the insecticide fipronil, while imidacloprid and permethrin were detected in 89% of the samples.

In March, new analysis showed that the destruction of the Kakhovka dam in Russian-occupied southern Ukraine has exposed 1.7km3 of polluted sediment containing up to 83,300 tonnes of highly toxic heavy metals. The researchers behind the study warned that rain and seasonal flooding will mobilise these pollutants, which they described as a ‘toxic time bomb’.

And in August, researchers in Germany warned that increasing ocean acidity, caused by the planet’s rising carbon dioxide levels, could weaken shark teeth and potentially impact their ability to hunt.

Boosting health

This year, Chemistry World ’s research pages covered numerous new techniques that chemists have developed to detect and treat disease. In January, researchers developed a simple lateral flow test that could enable early diagnosis of several types of tick-borne fevers. The tool relies on europium-based nanoparticles that fluoresce when they come into contact with an enzyme that is highly conserved across Rickettsia bacteria that are transmitted through the bites of infected ticks.

In April, researchers in the UK and Israel developed a simple blood test that could help to diagnose Parkinson’s disease before symptoms appear. The test measures the ratio of two different transfer RNA fragments to determine whether the disease is present. However, the early-stage test is currently not reliable across people from all ethnic backgrounds.

Also in April, John Rogers’ group at Northwestern University, US, reported on a new self-powered, bioresorbable temporary pacemaker that is smaller than a grain of rice. The device could be used to ensure stable cardiac rhythm in the days and weeks following heart surgery and could be particularly useful in the treatment of young children. The device eliminates a key problem associated with current technology that requires leads connected to an external power source that must be extracted later, often damaging recovering tissue and causing internal bleeding.

Another potentially transformative treatment reported this year is a new antidote for hydrogen sulfide poisoning. Based on two cyclodextrin units and an iron porphyrin, the compound has a higher affinity for hydrogen sulfide than human haem, meaning it can reverse the effects of poisoning.

Meanwhile, research groups in both China and the US harnessed AI to search for promising new antibiotics. A short-chain antimicrobial peptide , designed with the help of an AI model, was found to infiltrate bacterial membranes and could alleviate pneumonia symptoms in mice. Meanwhile, two small molecule drugs designed by AI models were found to kill bacteria faster than several frontline antibiotics and were also active against drug-resistant strains.

In August, researchers at Harvard Medical School reported on a previously overlooked link between lithium-deficiency and Alzheimer’s disease. The findings suggest that it may be possible in future to stall or reverse the disease by administering lithium, though this has not yet been demonstrated in patients.

Stunning syntheses

A growing number of skeletal-editing techniques are allowing chemists to modify complex molecules in ways that would have seemed fanciful just a few years ago. These techniques offer the ability to quickly generate analogues of potential drug compounds to rapidly assess whether small chemical changes can bring positive biological effects. New methods introduced this year include a sulfur–nitrogen exchange reaction that converts isothiazoles into pyrazoles and a carbon–nitrogen swap transforming indoles into benzimidazoles.

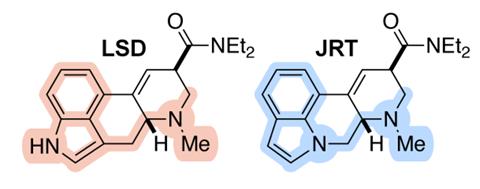

Two other studies that we reported on this year illustrate the power that such atom-swapping strategies could one day have in the search for better and safer medicines. In July, Richmond Sarpong’s team at the University of California, Berkeley showed that exchanging a single oxygen atom in morphine’s core structure for a methylene group creates an analogue that retains morphine’s painkilling activity while suppressing secondary interactions that are linked to addiction and respiratory depression. Meanwhile, swapping the positions of a carbon and a nitrogen atom in LSD’s structure was shown to produce a compound that offers the same therapeutic benefits as LSD, but without its hallucinogenic effects.

Some other impressive synthetic chemistry projects this year included a total synthesis of the anti-addictive alkaloid ibogaine that requires just seven steps, a light-powered molecular motor that stitches together catenane rings as it rotates, and a method for synthesising squaramides that uses filter paper as a reaction medium.

Weird structures

Unusual chemical species and strange bonding motifs regularly grace the pages of Chemistry World , and this year was no different. In March, we reported on boryne – the first molecule to feature a boron–carbon triple bond. July saw the first ever lanthanide–carbon triple bond , while in August researchers successfully synthesised methanetetrol – a carbon atom bonded to four hydroxyl groups – for the first time.

2025 also saw the discovery of a new nitrogen allotrope , hexanitrogen, which also happens to be the most energetic molecule ever synthesised. The researchers behind that work now have their sights on N10.

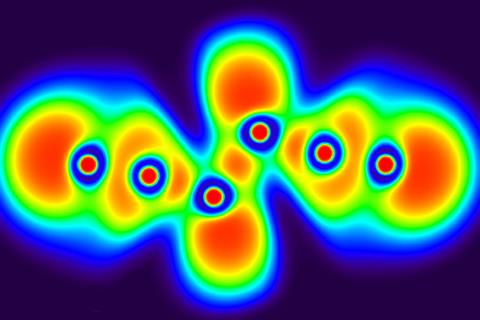

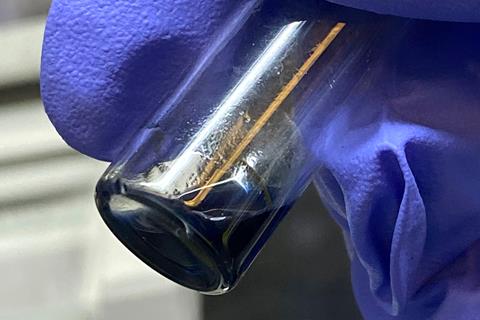

Researchers at the European XFEL facility in Hamburg used a record-breaking solid-state laser to drive shock compression waves into solid carbon samples, which enabled them to produce and characterise the first samples of liquid carbon. The samples formed at temperatures around 7000K and pressures over one million atmospheres, and lasted for a few nanoseconds – just enough time to capture some snapshots of the material’s structure with ultrabright x-ray pulses.

We also witnessed the first bulk synthesis of hexagonal diamond – a carbon allotrope with a hexagonal lattice rather than the conventional cubic lattice. The material was produced by applying pressures exceeding 200,000 atmospheres to a single crystal of pure graphite.

A nanoring made of 18 zinc porphyrins connected by butadiyne linkages and a series of spokes became the largest molecule yet to display global aromaticity – approaching the theoretical size limit for the phenomenon.

Heavy elements

Research into the superheavy elements at the very edge of the periodic table continues to push our understanding of chemistry’s boundaries. In early 2025, researchers in Germany measured the half-life of rutherfordium-252 to be around 60 nanoseconds – the shortest known half-life of a superheavy nuclei. The experiments revealed that certain excited states have longer half-lives, offering new insight into the fission process.

In the summer, experiments at the GSI/FAIR accelerator in Darmstadt, Germany, detected a seaborgium-257 nuclide – a previously unknown 22nd isotope of element 106.

Nobelium, element 102, became the heaviest element to have been directly detected as part of a larger molecule. Nobelium complexes containing hydroxide, water and dinitrogen ligands were created at a cyclotron particle accelerator at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, US. Meanwhile, berkelocene – an organometallic structure in which berkelium, element 97, is trapped between two cyclooctatetraene ligands – offered new insight into actinide bonding.

Rewriting the textbooks

Every year, chemists uncover new phenomena that appear to break longstanding ‘rules’ that many of us are taught from our earliest days studying the subject.

In January, computational chemists in the UK showed that alkyl groups are inductively electron-withdrawing relative to hydrogen , despite what you may have read in some older textbooks. While hyperconjugation leads to an overall electron-donating effect, the smaller inductive effect appears to have been misunderstood until now.

In March, another computational study suggested that perhaps it’s time to update the famous Woodward–Hoffmann rules that describe electrocyclic reactions. While these rules are often used to determine whether a given reaction is ‘allowed’ or ‘forbidden’, researchers from Cardiff University, UK, pointed out that it would be more accurate to use the terms ‘favoured’ and ‘disfavoured’ as, in some cases, the small energy differences between reaction routes mean that other factors, like steric interactions, can dominate.

That same month, a Russian team showed that it is possible to carry out solution-phase organic reactions at temperatures as high as 500°C – conditions that are generally thought to lead to thermal degradation of solvents and substrates.

In September, researchers in China raised eyebrows by asking whether chemists really need to stir their reactions. ‘Chemical reactions in nature occur without stirring – raising the question of whether stirring is truly necessary,’ Zhong Quan Liu from the Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine told Chemistry World. The team tested hundreds of reactions, some up to kilogram scale, and found that stirring didn’t influence the rate or outcome of the processes. However, the study drew mixed reactions from the wider community, with other researchers pointing out that in many types of chemistry – including faster reactions, photochemistry, reactions involving multiple phases or those carried out on large scale – stirring is often critical.

Who knew?

To wrap things up, let’s take a look at some weird, wacky and wonderful findings that caught the eye this year.

In June, the term ‘in-insect synthesis’ entered the chemist’s lexicon. Researchers in Japan showed that caterpillars fed a diet of boiled kidney beans, agar, water and a belt-shaped nanocarbon would selectively transform the molecular substrate into an oxygen adduct. ‘I won’t say that in-insect synthesis will completely replace in-flask, but it is an option for derivatising the molecules that we synthetic chemists synthesise over years, worldwide,’ lead researcher Kenichiro Itami told Chemistry World at the time.

In July, researchers in China and the US showed how ‘microlightning’ generated by peeling sticky tape could be used to ionise reactants and drive chemical reactions, including the Menshutkin reaction between pyridine and methyl iodide.

In August, a team from Nevada, US, heated a solid gold sample to 19,000K – over four times the metal’s melting point – without the material losing its crystalline structure. The researchers suggest that, as long as a material is heated fast enough, there may potentially be no limit to how high a solid sample can be superheated before it loses its structure.

Researchers in Durham, UK, solved the longstanding mystery of why some sunscreens stain clothes red when they’re bleached. The cause is a common sunscreen ingredient called diethylaminohydroxybenzoyl hexyl benzoate. Bleaching can dearomatise one of the compound’s rings and install two chlorine atoms onto the same carbon – it’s this ipso -dichlorinated product that absorbs short- and mid-wavelength visible light, leaving only long wavelengths that give a crimson hue.

Finally, before you brew another cup of civet coffee to drink while perusing the next section of the magazine – researchers have finally worked out why it’s so delicious. It all comes down to the natural fermentation that occurs in the civet cats’ digestive system. Civet coffee beans, which can cost £1000 per bag, have a higher fat content and elevated levels of caprylic acid and capric acid methyl esters – compounds known for their flavour-enhancing properties and dairy-like aroma. Now that you understand the science behind the price-tag, time to put the kettle on.

No comments yet