High levels of per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) have been found in the sprays and cloths that people around the world have been using on their glasses to prevent fogging when wearing a face mask or shield during the pandemic.

The Duke University team in the US used mass spectrometry to analyse four top-rated anti-fogging sprays and five popular demisting cloths sold on Amazon, and it turned out that all of them contained fluorotelomer alcohols (FTOHs) and fluorotelomer ethoxylates (FTEOs), which are two relatively unknown PFAS chemicals. To the best of their knowledge, the researchers said, FTEOs have not yet been identified in any other commercial products.

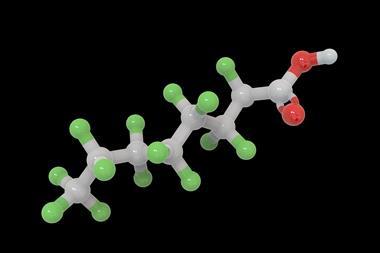

PFASs are a controversial class of persistent, highly mobile and potentially toxic compounds. The two most well-studied PFAS chemicals – perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) – are linked to serious health problems such as impaired immune function, cancer and thyroid disease.

‘Our tests show the sprays contain up to 20.7mg of PFAS per millilitre of solution, which is a pretty high concentration,’ says Nicholas Herkert, first author on the study.

As much is not yet known about FTOHs and FTEOs their potential health risks are unclear, but the researchers said the literature suggests that after inhalation or dermal absorption of FTOHs these compounds could break down in the body to form PFOA or other long-lived PFAS chemicals associated with toxicity. They noted that all the spray mixtures examined in the new study did demonstrate significant cell-altering cytotoxicity and adipogenic activity in assays.

The Duke scientists, who claim that their experiment is only the second ever to focus on FTEOs, noted that the study’s small sample size means additional work will be required to flesh out their initial findings. They suggested that larger studies that include not only in vitro but also in vivo testing are the logical next step.

FTOHs and FTEOs could be metabolic disrupters, but Herkert explained that this can only be verified through in vivo testing on whole organisms. It is also possible that studies with larger sample sizes would identify other undisclosed chemicals in the sprays or on cloths, he added.

References

NJ Herkert et al, Environ. Sci. Techno., 2021, DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.1c06990

No comments yet