‘Crystal structure prediction is, after years of hard work by many, many groups, finally reaching the point where it’s going to have large impacts in organic materials.’ So says Gregory Beran, at the University of California Riverside in the US, who has shown that combining hybrid density functional theory modelling with intramolecular energy correction can reliably predict the complex crystal structures of pharmaceutical compound axitinib. Beran’s strategy can, in tandem, also distinguish between salt and co-crystals in multi-component crystals, a long-standing challenge in organic crystal modelling.

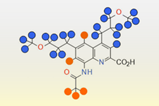

Axitinib is a targeted anti-cancer medication commonly prescribed to patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma after other systemic treatments. It works as a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, blocking vascular endothelial growth factor receptors that drive tumour growth and metastasis.

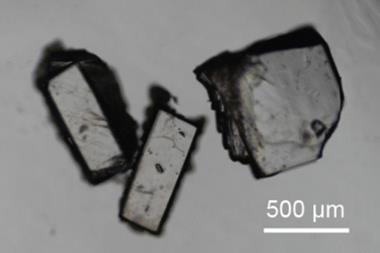

But developing axitinib has been complicated by its ability to crystallise in multiple forms, known as polymorphism. It can exist in five known non-solvated crystalline structures, each with distinct physical and chemical properties that influence solubility and bioavailability. Initially, chemists thought form IV was the most suitable candidate for development, until further experimental screenings revealed form XXV, and later form XLI, which is the most thermodynamically stable and ultimately received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2012.

‘It was a case where twice, chemists thought they had their target and had to back-pedal,’ says Beran. ‘Crystal structure prediction could have really helped avoid this.’

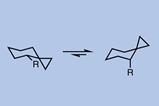

Researchers have since applied density functional theory (DFT)-based crystal structure prediction to axitinib, but these approaches often rank polymorph stabilities poorly. Many systems also suffer from density-driven delocalisation errors, which can lead to incorrect predictions of salt formation in co-crystals. A known way to address these issues is to combine DFT with intramolecular energy correction.

Beran has now produced the first 0K crystal structure prediction of axitinib that aligns closely with experimental data. He optimised several known crystal structures of axitinib lying within 15kJ mol⁻¹ of the global minimum, which is the lowest energy conformer. He also predicted a version of form IV that contains two independent molecules in its unit cell, as well as multi-component crystals with fumaric, suberic and trans-cinnamic acid.

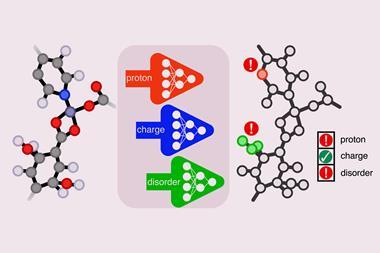

To generate these structures, he applied periodic planewave density functional theory and exchange-hole dipole moment dispersion correction to relax the crystal structures in atomic positions and lattice parameters. Constrained optimisations mapped energy curves for proton transfer coordinates in the multi-component crystals. And he refined the crystal energies using periodic density functional theory with both generalised-gradient approximation and hybrid functionals. In addition, intramolecular correction refined the single-point periodic density functional theory energies, and Orca software performed polarisable continuum model treatment for low- and high-level calculations.

The crystal structure prediction revealed that most of the low-energy predicted structures of axitinib are known experimentally, and that form XLI is the global minimum structure at 0K. The study also distinguished the axitinib salt formed with fumaric acid from co-crystals involving suberic or trans-cinnamic acids.

‘While potentially expensive, the study points towards a methodology for predicting whether two molecules would crystallise as a salt or co-crystal,’ says Sarah (Sally) Price, a theoretical chemist at University College London in the UK. ‘This is a whole area of other experimental possibilities to model in the computer, and that’s exciting.’

‘[Crystal structure prediction is] still not perfect and there are still issues we need to solve as a community, but I think it’s poised to really start making a difference on what people can do,’ says Beran.

No comments yet