New non-invasive sensor could check blood glucose levels using tears

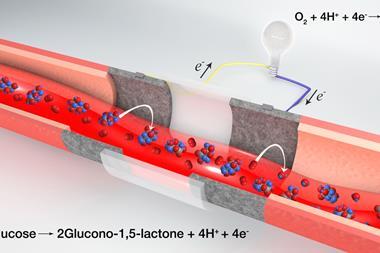

People with diabetes may soon benefit from pain-free blood glucose monitoring, thanks to a sensor that measures the sugar in tears.

Current techniques for glucose self-monitoring involve drawing blood onto disposable test strips and analysing the samples with a separate device. This painful, multi-step approach deters some patients receiving insulin therapy from testing their glucose levels as often as is recommended. A team from Arizona State University in the US believes that its non-invasive method would encourage diabetes patients to test their glucose levels regularly.

The concept of using tear glucose levels as an indicator of blood glucose is not new. However, it has been tricky to realise because of the small volumes involved and the potential for inconsistent sampling, which make it hard to reliably correlate the results with blood glucose concentrations. Jeffrey La Belle and his team have tackled this engineering challenge to design a device which combines a quick and simple sampling approach with a detector that is sensitive enough to give accurate measurements in vivo.

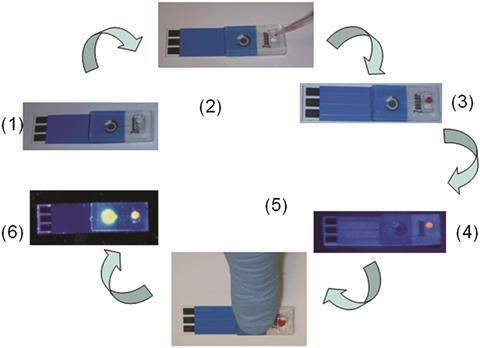

The result is a prototype ‘Touch’ sensor, which requires only 5.8µL of tear fluid. A disposable soft foam tip absorbs tears by touching the eye ‘for a fraction of a second’, its creators explain. La Belle is reassuring that the method is easy to use: ‘If the person has worn contacts, they are touching their eye more than they ever would using our device.’

Squeezing the device then pumps the sample into the sensing chamber, where the electrochemical activity of a glucose dehydrogenase enzyme produces a signal in the detector. The prototype then estimates blood glucose levels based on a correlation with tear glucose concentration, giving results in a wide range between extreme hypo- and hyperglycaemia. The sensor is also highly sensitive and specific for glucose, which limits the risk of false results due to detecting other sugars.

Koji Sode, who researches biosensors at Tokyo University of Agriculture & Technology in Japan, says the combination of sampling device and sensor is ‘very neat and very smart’, but is cautious about predicting the impact of this emerging technique: ‘We are not able to finalise whether tear glucose concentration is good for diabetes control.’

An intial animal trial demonstrated the safety of the sampling mechanism and a moderate correlation between tear- and blood-glucose concentrations. La Belle’s team now plans to optimise the device and hopes to begin testing on humans soon, with the aim to commercialise the sensor within two to three years.

According to Vinay Nagaraj, a researcher of metabolic disorders at Midwestern University, US, ‘the availability of such a device will revolutionise how patients self-monitor blood glucose, the frequency of glucose measurements and ultimately the treatment as well as management of diabetes’.

References

J T La Belle et al., Chem. Commun., 2016, DOI: 10.1039/c6cc03609k

No comments yet