The forgotten discoverer of electrolysis returns to the spotlight

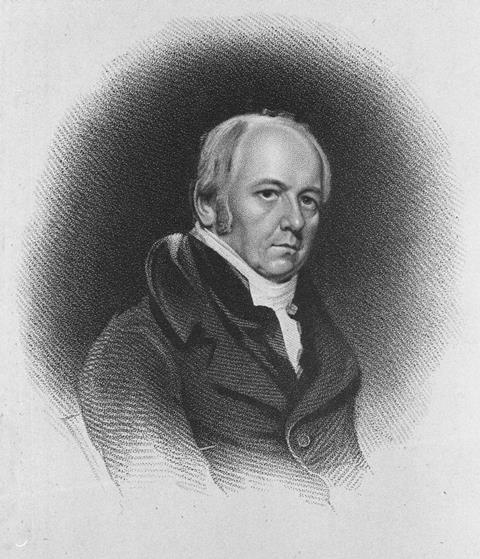

William Nicholson

British chemist and journalist (1753–1815). Founder of Nicholson’s Journal and discoverer of electrolysis

‘A fox knows many things, but a hedgehog knows one big thing.’ In 1953, the philosopher Isaiah Berlin drew on this cryptic and mysterious sentence, by the Greek poet Archilochus, to distinguish between the conceptions of history in Russian literature. It’s fun to ask who are chemistry’s hedgehogs and who the foxes? One person to classify might be the hugely influential but largely forgotten figure of William Nicholson, the discoverer of electrolysis.

Born in London to a respectable middle class family, Nicholson made his name with the East India Company, with whom he travelled to China and spent a couple of years in India. When his father died in 1773 he returned to Europe and got a job in Holland as a discreet investigator and agent on behalf of Josiah Wedgwood, who was worried about being cheated. But these short term contracts led nowhere, and Nicholson returned to London where he moved into a house with Thomas Holcroft, a journalist and playwright. Through Holcroft he started getting small writing assignments and minor technical consultancies; he also taught mathematics and translated French novels into English. This succession of small gigs were enough to keep him and his new wife and family housed and fed as he steadily built up his connections in London.

Born in London to a respectable middle class family, Nicholson made his name with the East India Company, with whom he travelled to China and spent a couple of years in India. When his father died in 1773 he returned to Europe and got a job in Holland as a discreet investigator and agent on behalf of Josiah Wedgwood (Chemistry World, January 2013, p68), who was worried about being cheated. But these short term contracts led nowhere, and Nicholson returned to London where he moved into a house with Thomas Holcroft, a journalist and playwright. Through Holcroft he started getting small writing assignments and minor technical consultancies; he also taught mathematics and translated French novels into English. This succession of small gigs were enough to keep him and his new wife and family housed and fed as he steadily built up his connections in London.

Through Wedgwood, Nicholson became secretary of the General Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain. He joined and ran several coffee houses – circles where business, politics or science were discussed. Through the Baptist Chapter Coffee House, of which Wedgwood was a member, Nicholson met many of the leading ‘philosophers’ of the time, including the Portuguese ex-monk and instrument-maker Jean Hyacinthe Magellan, and the phlogistonist chemists Richard Kirwan, Adair Crawford and Joseph Priestley, as well as the Italian-born physicist Tiberio Cavallo.

He also began doing research of his own, driven by his conversations about science. Perhaps inspired by Kirwan, who had devoted much effort to the determination of the densities of salt solutions, Nicholson developed an improved hydrometer.

Hydrometers were nothing new. In the 5th century the brilliant neo-Platonist astronomer and mathematician Hypatia was instructed to build one, a weighted brass tube with notches on its length, corresponding to density, that floated upright. In 1669, Robert Boyle reported the use of glass bulbs to measure the densities of liquids. He refined and developed his idea into a method for assaying coins: the coins could be fixed to the bottom of a hollow metal sphere to which was soldered a rod engraved with a scale. From the buoyancy the density of the coin could be determined.

In the 1770s, the instrument maker Daniel Fahrenheit proposed a new design that would allow the density of any liquid to be determined. The hydrometer consisted of a sealed tube, with a weight at the bottom to hold the device upright in the water. The rod projecting from the top now bore only a single mark. After weighing the device dry, it was floated with weights added to the dish until it floated with the mark level with the water. Next, with the device immersed in the test liquid, the process was repeated. The ratio of the two laden weights gave the density.

In 1784, Nicholson combined the Boyle and Fahrenheit approaches. His device was equipped with a dish at the top and a basket at the bottom. It floated at the mark in water with a weight of 1000 grains loaded on the dish. The loading would change in a different liquid, analogously to Fahrenheit’s device. But working with distilled water, the basket could be loaded with a known mass of unknown solid. Adjusting the weights at the top gave the weight of displaced water, from which the density of the solid was easily calculated, with excellent precision.

Alongside his scientific contributions Nicholson wrote at a phenomenal rate from textbooks to encyclopaedias, and translating French chemistry texts by Fourcroy and Chaptal. He also began Nicholson’s Journal, a direct rival to the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions. Upset by the competition, the Royal Society’s secretary Joseph Banks turned down Nicholson’s candidacy for Fellowship on the grounds that the society was no place for ‘sailor boys’.

In 1800, Banks received a manuscript from Alessandro Volta describing his ‘battery’, a stack of alternating copper and silver coins that provided a continuous source of electrical sparks. Banks discussed this with a friend, the surgeon Anthony Carlisle, who turned to Nicholson for help in replicating the experiments. Needing to connect the stack of coins to an electrometer they added a little water to improve the contact. To their surprise they saw bubbles in the liquid. Intrigued they put the wires from their battery into a tube of river water and saw streams of bubbles from each wire – hydrogen and oxygen, the components of water suspected by Lavoisier. They published immediately in Nicholson’s Journal. The paper lit the fuse that led Humphry Davy at the Royal Institution, who had himself learned chemistry on Nicholson’s texts, to the isolation of the alkali metals.

In 1800, Banks received a manuscript from Alessandro Volta (Chemistry World, June 2011, p58 ) describing his ‘battery’, a stack of alternating copper and silver coins that provided a continuous source of electrical sparks. Banks discussed this with a friend, the surgeon Anthony Carlisle, who turned to Nicholson for help in replicating the experiments. Needing to connect the stack of coins to an electrometer they added a little water to improve the contact. To their surprise they saw bubbles in the liquid. Intrigued they put the wires from their battery into a tube of river water and saw streams of bubbles from each wire – hydrogen and oxygen, the components of water suspected by Lavoisier. They published immediately in Nicholson’s Journal. The paper lit the fuse that led Humphry Davy at the Royal Institution, who had himself learned chemistry on Nicholson’s texts, to the isolation of the alkali metals.

In spite of his fame, Nicholson struggled to make ends meet. Deeply in debt, his journal was taken over by the more successful Philosophical Magazine. He died at home in London in 1815, his name almost forgotten except, perhaps, by geologists who used his hydrometer. A jack of many trades, a master of many, perhaps he was a superposition of both hedgehog and fox.

References

W Nicholson, Mem. Litt. Phil Soc Arts, 1784, 370

No comments yet