Pseudoscience now has more serious consequences than a few bent spoons

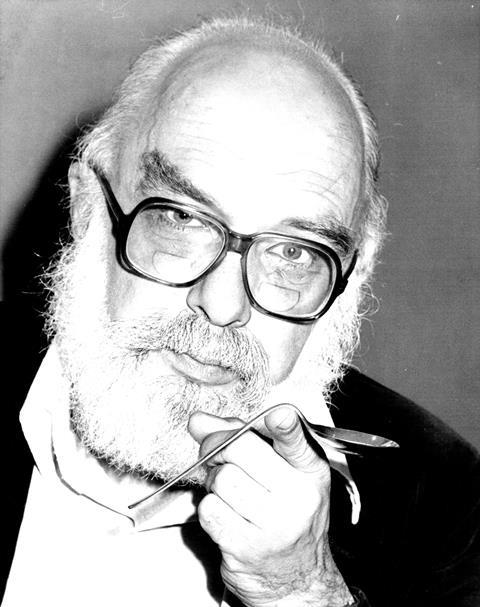

The death of magician and debunker of frauds James Randi was a reminder that even pseudoscience and charlatanry used to come from a kinder world. Randi’s arch-antagonist was the ‘psychic’ Uri Geller, who always seemed to be on 1970s chat shows bending spoons with the power of his mind. I came across Randi (and witnessed a demonstration of his stage magic) while working for Nature after the journal had just published the notorious ‘memory of water’ paper by French immunologist Jacques Benveniste. The editor enlisted the magician to join the team that travelled to the French labs to witness a (failed) attempt to replicate the studies in which a biological molecule was said to retain its activity after being diluted to the point of total absence.

That is now seen as one of the classic examples of pathological science, joining the likes of the polywater affair of the late 1960s and the cold fusion episode of 1989. Polywater – an alleged new form of water, with the consistency of soft wax – was straightforwardly disproved and eventually disowned by its Russian ‘discoverers’. But both cold fusion and the memory of water live on in the imaginations of some, lodged now somewhere between a fringe curiosity and a conspiracy theory.

Yet for all the rancour of the arguments they elicited, these claims never became as confrontational, politicised and downright lunatic as those surrounding, say, the supposed causes of Covid-19 (5G wifi, bioweapons) or the ‘risks’ of the vaccines against it (allegedly laced with microdevices that will turn us into Bill Gates’ robots). One shudders to imagine what might have become of cold fusion under the Trump administration.

An exploitative business

Despite Randi’s efforts, pseudoscience has now gone mainstream: it infects public and political discourse on the pandemic, on climate, on medicine and vaccination, on abortion, race and culture. It is no longer propagated just by mavericks and cultists such as Geller or David Icke, but is funded by ultra-conservative thinktanks, opportunistically exploited by politicians, nourished and spread by the misinformation fire-hoses of the Kremlin and far-right hate networks, and apparently accepted as part of the business model of social media companies. Geller ultimately wasn’t much more than an entertaining distraction. Today’s equivalents are straining the fabric of democracy.

The cost of making misleading or false claims is minimal

As media scholar Gavan Titley points out in his new book, provocatively titled Is Free Speech Racist?, dealing with misinformation of this kind is an unequal battle. The cost of making such misleading or false claims is minimal: a tweet from someone with a large following is all it takes. But mounting a rigorous counter-argument based on facts can be extremely time-consuming, and of limited impact anyway once the falsehood has been released into the wild, given the relentless churn of today’s information ecosystems. I discovered this myself when reviewing Christopher Booker’s 2009 climate-change-denial book The Real Global Warming Disaster. I picked just three of the countless claims it made and tracked down the facts. All of them disproved Booker’s assertions, but to do that for the whole book would be a thankless task no one can be expected to undertake – and my review in any case doubtless had minimal effect compared to the book itself.

This is why, Titley argues, we need to rethink what we mean by free speech. Contrarians like to present themselves as outsiders who the ‘elite’ or ‘establishment’ are trying to suppress because they voice uncomfortable or politically incorrect truths. That’s the image cultivated by Charles Murray, whose new book Human Diversity rehashes his old argument that there are ‘racial’ differences in average IQ (adding for good measure supposedly innate differences of ability between the sexes and between social classes). This ‘silenced outsider’ puts his case not only in a book published by a big publisher but also in major newspaper editorials; it masquerades as what Titley calls ‘renegade intellectualism’.

Mute point

But the right to free speech does not mean the right to a platform. The US election offered the astonishing spectacle of pro-Trump Fox News cutting away from the president’s press secretary as she contested the result, because even they could not support the stream of lies she was telling. Titley suggests that there are some issues on which the media has both the right and the obligation to consider the debate to be over. Climate change is surely one, and so is racist pseudoscience. It’s not about shutting people up, but about using the mute button.

The Covid-19 ‘infowar’ has not perhaps yet reached that stage – much is still unknown, and debates should continue on the best policy response. All the same, some of what is now being said about ‘herd immunity’, the economics of lockdowns, and the alleged unreliability of testing statistics amounts to misinformation. As with climate change, there are now some contrarian voices from whom we will not productively hear any more.

As the pandemic, the state of the environment and recent political events have shown, there is rather more at stake now than the reality of spoon-bending.

2 readers' comments