Derek Lowe makes the case against using ‘frequent hitters’ in your assays

You might not think that the makeup of a compound screening collection could set off many arguments, but there are a few issues there that will do the trick almost every time. Take the concept of ‘frequent hitters’, compounds that tend to show up as hits against many and varied targets. Ask yourself what might seem to be a simple question: do you want such things in your collection?

Hit machines

One side of the dispute says that yes, of course you do. The purpose of screening a compound collection is to ind hits – it does no one any good to come up empty. And it’s not like people are looking for ready-to-wear clinical candidates out of a random screen. Many researchers just want so-called ‘tool compounds’ that can be used in cellular or puriied protein assays to help unravel the biochemistry of a given target. It doesn’t have to be beautiful, and it doesn’t have to be from a unique structural class. It just has to work. There are such things as ‘privileged structures’ in medicinal chemistry, so why not cast your line where the ish are biting?

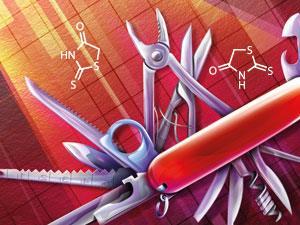

But the other side of the debate has some objections. To the sceptical mind, a compound that you can see binding to a wide variety of proteins is probably going to bind to a lot of proteins in general. This doesn’t give you conidence in the results of a cellular assay – if your ‘tool’ compound is a Swiss army knife in disguise, rather than the perfectly itted socket you were hoping for, it’s probably going to mess with things you didn’t want it to. Why take the chance? There are other worries, too: some of those frequent hitters get that way though mechanisms that not everyone appreciates, such as covalent attachment, which you need to take into account. And if you’re looking for more than just a tool compound, then something from a promiscuous structural class is the last place you’d want to start.

There are several compound classes that always end up in the middle of these disputes. Polyphenols are a classic example. They turn up showing potency against the strangest targets, and sometimes they’re the only compounds that even make the cut. Plenty of highly active natural products have such structures in them. They’re clearly hot stuff. Perhaps too hot, though – really selective polyphenols are thinner on the ground. That makes them tricky in vitro, but in vivo they’re even harder to work with. These compounds tend to be cleared quickly in live animals, and attempts by the medicinal chemists to make their structures more tractable often end up wiping out their initial activity. There are plenty of medicinal chemists who won’t even touch leads from this group.

Class war

Another contentious class is the rhodanines. They’re an interesting-looking little bunch of ive-membered heterocycles that hit over and over in all kinds of assays. They have their fans, but they’ve also been referred to as ‘polluting the scientiic literature’. Truthful disclosure: I lean towards the latter view, but that’s partly because I spend my time trying to discover drugs. Any class of compounds that lights up the assays over such a wide area scares me. I have a rough idea of how much I don’t know about the contents of whole cells and whole animals, and it certainly is a lot. I would honestly only work on a rhodanine under extreme duress, perhaps against a wildly highvalue target where nothing else has worked. Even then, I would not rate my chances very highly. Drug discovery seems quite hard enough already without taking on the rhodanine challenge at the same time.

But look through the journals: hardly a month seems to go by without some paper extolling the virtues of some rhodanine as a new ligand against the vitally important ‘whatever-ase’ protein, or what have you. I really wonder how many of these results would hold up after a determined effort to check selectivity, or how many of the groups reporting them have even thought about doing such a thing (too much of that will hurt the publication chances, apparently). No, perhaps I’ll start a fight of my own by saying so, but as far as I’m concerned, rhodanines and their ilk are guilty until proven innocent.

No comments yet