Looking beyond today’s periodic table

The periodic table is one of the most popular and useful classifications of modern science. Its predictive and explanatory power is invaluable. It’s one of the few things created by scientists that has infiltrated popular culture, prompting artistic responses and songs that children learn to this day. And chemists – I think it is fair to say – love it!

So how did we arrive at it? What factors contributed to formulating such a successful and unique pictorial depiction of chemical elements?

There is more than one story that one can recount to answer this question. The obvious thing is to go back to Dmitrii Mendeleev. How he formulated his proposed classification of elements in terms of atomic weights is one of the most celebrated parts of chemical history.

Intriguingly, what is often left out of that story are the disagreements within the chemical community about whether Mendeleev’s table should be adopted. It was not the only table that was proposed at the time. However, Mendeleev’s table purported to be more complete, not just in the number of elements it depicted but also in the range of properties it took into account. A comparison of different epistemic values (namely, of predictiveness, completeness, numerical accuracy and simplicity) figured in choosing Mendeelev’s table over the other candidate representations.1 In the end, its ability to predict previously unknown elements played the deciding factor for the acceptance of Mendeleev’s table.

This, in a nutshell, is the story of how we got to our well-known periodic table. (Admittedly, this omits interesting details such as how the understanding of isotopes eventually led to the periodic law to be about atomic numbers and not atomic weights.) However, there are two other aspects of chemical history that need to be illuminated to understand how we arrived at today’s famous representation of elements and which have been part of chemical practice since long before Mendeleev’s time.

A symbolic role

The first is the role of symbols, which have been used for chemical purposes for thousands of years and hold a very important role in the practice of chemistry. As German chemist August Wilhelm von Hofmann put it in 1865: ‘(s)ymbolic formulae… would deserve to rank among the chemist’s most powerful instruments of research’.2

Symbolism goes all the way back to the alchemists. Alchemists were particularly talented at inventing symbols, not just for what we recognise today as elements and substances, but also for depicting properties of matter. The circle was associated with gold, while water and earth (which were two of the four Aristotelian elements) were represented by inverted triangles. As historian of chemistry Maurice Crosland points out, geometrical figures were used to depict properties of substances or information about their constitution. Interestingly, this is something that John Dalton also did in the 19th century.

Another fascinating aspect of alchemical symbolism that we can also find in today’s depiction of elements is the use of colour symbolism. Alchemists used colours to identify elements, substances or properties: for example, black was associated with the idea of impurity, white was associated with silver and (for European alchemists) red was associated with gold.3 Colour-coding is far from new!

The second relatively neglected aspect of chemical history concerns the formulation of different kinds of tables. Tables have been invented to classify not just chemical elements, but substances, properties and reactions too. The most notable examples are perhaps affinity tables, which aimed to depict the tendency of substances to react with each other. But one can find other classifications in the history of chemistry, such as Guillaume-François Rouelle’s classification of natural salts in 1744 or Torbern Bergman’s classification of minerals in 1782.4 Classification in organic chemistry is also a major chapter of this story, one that deserves separate analysis to fully appreciate it.

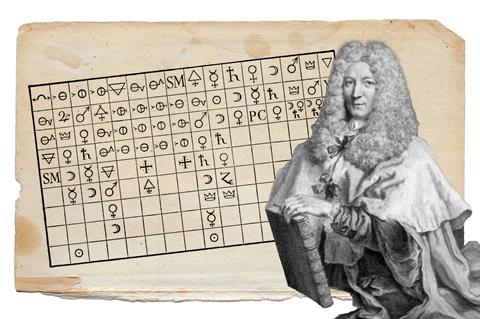

The history of symbols and tables is of course intertwined. This can be seen through the example of Etienne-Francois Geoffroy, who revived alchemical symbolism in the 18th century to construct affinity tables. It is worth discovering Geoffroy’s tables as they look quite mystical: the symbols include crowns, crescent moons and crosses.

These are just some nuggets of the rich history of symbols and classifications in chemistry. As with any fascinating story, it prompts follow-up questions: how did chemists agree upon a common set of symbols? What were the sociological, political or cultural factors that figured in this story? Were there disputes, and on what grounds were they settled? I’ve yet to discover the answers but I’m excited to share them once I do!

In any case, it is worth thinking about all of this the next time you come across the periodic table. Among everything else that we’ve been taught about it, the periodic table is something very significant: a paradigmatic symbol of human civilisation.

References

1 K Pulkkinen, Ambix, 2020, 67, 174 (DOI: 10.1080/00026980.2020.1747325)

2 A W Hofmann, Introduction to Modern Chemistry. London, 1865, p87

3 M P Crosland, Historical studies in the language of chemistry. London: Heinemann Educational Books, 1962, pp 28–30

4 M P Crosland, Historical studies in the language of chemistry. London: Heinemann Educational Books, 1962, p124, p147

No comments yet