A philosophical discussion about how much we can trust our senses

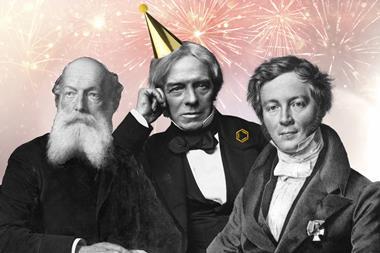

I love anniversaries. They can make you think of things you wouldn’t normally ponder, or prompt you to dive into stories of the past. This happened to me with benzene recently. It’s been 200 years since Michael Faraday isolated it, yet his achievement is still significant in many unexpected ways.

What struck me the most about benzene’s story was the description of its smell. Faraday characterised the liquid substance as smelling of oil gas and almonds. What a peculiar combination!

This reminded me of the courses I took in the organic laboratory as an undergraduate. The teaching assistants started by teaching us the simplest methods of examining substances and I distinctly remember how important sense perception was to their everyday practice. Smell was perhaps the most important of all senses. One teaching assistant tried very persistently to describe the smell of a sample she was making. She struggled because, as she said, over her years in the lab she had lost her sense of smell.

The importance of sense perception in chemistry comes in stark contrast to how senses are evaluated in philosophy. Basically, senses cannot be straightforwardly trusted when forming beliefs about the world.

The ancient skeptic Sextus Empiricus, who lived in Greece around the 2nd and 3rd century CE, gave a detailed analysis of why senses are considered an unreliable source for knowledge of the external world through his presentation of Pyrrhonian scepticism. First, sense perception differs for different creatures: a flower may not smell the same to a human as it does to a bee. Second, a human may perceive a thing differently under different circumstances. Don’t things often smell different when we have a cold than when we do not?

Also, appearances of an object can be contradictory depending on the senses we employ. Sextus Empiricus gives the example of ‘sweet oil’, which ‘pleases the sense of smell but displeases the taste’. He also points at the incompleteness of our sense perceptions. As some people are born without the sense of sight, it is similarly conceivable that humans may lack some sensory organ that would allow them to perceive objects in a completely different way.

Does this mean that we can know nothing of the world through our senses? This is not an inevitable conclusion. Appearances do not directly correspond to how objects truly are, yet they can be informative as to their nature.

It is not that chemists ever expected to uncover the true nature of benzene by smelling it

Let me now jump some centuries forward to Bertrand Russell and GE Moore, who examined this topic in the context of the idea of ‘sense-data’. Moore defines sense-data as: ‘a class of entities of which we are very often directly conscious, and with many of which we are extremely familiar. They include the colours, of all sorts of different shades, which I actually see when I look about me; the sounds which I actually hear; the peculiar sort of entity of which I am directly conscious when I feel the pain of a toothache, and which I call “the pain”; and many others which I need not enumerate’.1

Russell distinguishes between sense-data (smell, sound, colour), the sensation of those data, and the object itself.2 This is important because everything we know about objects is through their sense-data, but this doesn’t mean that objects themselves are their sense-data. That is, benzene is known by means of its smell but that doesn’t necessarily imply that it is identical to that smell nor that it has that property of smell (similarly, we cannot say for sure that the brown colour we see is that of the table we look at). Russell believed that even though the sense we get from the perception of objects may not correspond to the nature of an object, the object (or, as he later thought of it, its logical construction) does exist as the cause of those sense-data.

Viewed from this perspective, one can appreciate how smell (and other sense-data) figure in chemical practice. It is not that chemists ever wished or expected to uncover the true nature of benzene by smelling it. Most commonly, sense-data are invoked to distinguish between substances (especially when they resemble each other in terms of our other senses) or to make inferences about certain properties they have. So even though senses can be very deceiving and not particularly revealing as to the nature of things, they do play a very important role in understanding them better.

Even the most casual act of smelling a substance prompts questions about what it means to perceive the world and about how to understand it through our sensations. Of course, nowadays we know that smelling and touching unknown substances can be very dangerous. But I think it is still fair to say that using one’s senses is an important element of practising both chemistry and philosophy.

References

1 G E Moore, P. Aristotelian Soc., 1910, 10, 36 (DOI: 10.1093/aristotelian/10.1.36)

2 B Russell, The problems of philosophy. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001

No comments yet