From correcting research imbalances to placing value on lived experiences

When I want to convince someone that a feminist perspective on science is valuable and worthwhile, the go-to example I use is – I’m sad to say – women’s health. The way women’s health has been affected and impacted by sexism is shocking and quite frankly disappointing given the enormous advances science in general has achieved.

Feminist philosophy of science and feminist bioethics are fields that try to overcome gender injustices in medicine. There are two main ways in which a feminist perspective on science aims to improve women’s health. The first is by pointing out the mechanisms by which sexism has systematically affected the health and wellbeing of women, leaving them untreated or misdiagnosed. To some extent this concerns conditions that are exclusively feminine, such as conditions relating to pregnancy, contraception or maternity. A characteristic example is the so-called vaginal mesh scandal where women’s reports of complications with this surgical implant were overlooked, leading to pain, injury and even death.

However, there are also conditions that affect both sexes for which women are often marginalised or cast aside, such as cardiovascular diseases and strokes.1 It often takes a long time to correctly diagnose a stroke in women as its characteristic symptoms sometimes differ between the two sexes. Focusing primarily on the symptoms exhibited by men leaves women untreated for longer, with worse outcomes as to their recovery.

In this context, the contribution of feminism is to bring out such cases of medical mistreatment and to identify how their root causes lie in the sexist and androcentric prejudices that underwrite medical research, practice and education. For example, a large element that has contributed to the misdiagnosis of stroke in women lies in the sex disparities that exist in randomised clinical trials.2 Another more general problem concerns the power dynamics among patients and doctors and how these have been negatively influenced by gender stereotypes.

Positive perspectives

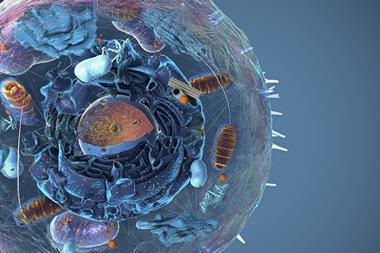

Nevertheless, there is also a second, more positive way in which a feminist perspective can both help overcome existing injustices and contribute to the better medical treatment of women. Feminist studies of science can help us appreciate the different factors that influence how knowers produce knowledge claims. Specifically, it is argued that what we know and how we know it is influenced by our unique positions and perspectives in the world. We are creatures with bodies and as such how we relate to others and to the (physical, cultural and social) environment in which we are situated influences how we understand the world around us.

A classic example that is often given to explain this idea is describing a building entrance. A person using a wheelchair may highlight completely different aspects of the entrance than a walking person, particularly if steps or inappropriate doors make the building inaccessible to them. But both descriptions are still accurate.

Similarly, this idea of embodiment and situated knowledge applies to how medical knowledge and consequently treatment are developed. After all, medicine studies our bodies and how we experience the world through them. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the lived experience plays a very important role in how both doctors and patients understand a certain disease or condition. The example of the vaginal mesh scandal is again here illustrative as the enormous pain that was experienced by certain women was initially disregarded by doctors.

Broader views

On the other hand, the lived experience of a debilitating condition can hinder a patient’s viewpoint too. How should one inform a patient who is in pain about their condition in such a way as for them to be able to make a well-informed decision about their body? This is a very difficult question as the decision-making autonomy of patients may be compromised by the effects of their condition (for example, because they involve chronic pain). Such ethical questions need to be investigated to help medical practitioners do their job in a way that is better both for them and their patients.

Being more sensible towards the lived experience of patients, and women in particular, is not a new approach. In the 11th century, the women of Salerno in Italy were famous for their medical studies of the female body and for the innovative treatments they had developed. Part of their success lay in that – as women – they had a much greater understanding of the female body, and I would venture, much more empathy towards their experiences. Funnily enough, their achievements were buried for centuries, with their best-known representative – Trota – thought by scholars to be a man (because how could women have been so successful in medicine?).

It’s time to bring back the mentality of the Salerno women to overcome the systematic injustices women suffer as patients. After all, we are talking about the wellbeing of half the world’s population!

References

1 C W Yoon and C D Bushnell, Journal of stroke, 2023, 25, 2 (DOI: 10.5853/jos.2022.03468)

2 B Strong et al, JAMA Neurology, 2021, 78, 666 (DOI: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.0873)

No comments yet