Unpublished images should be brought to light to aid science communication and speed up discovery

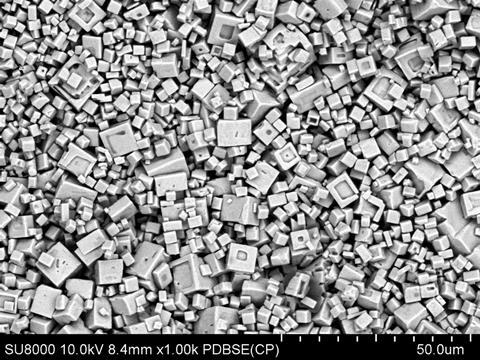

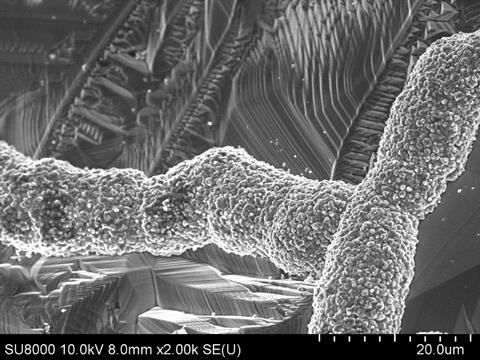

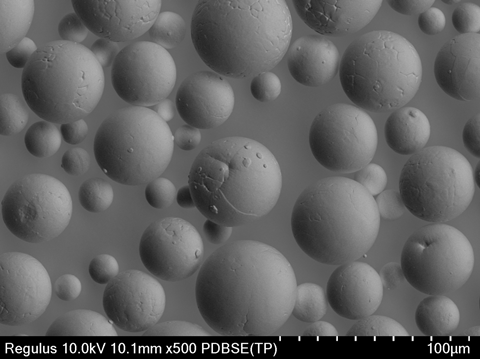

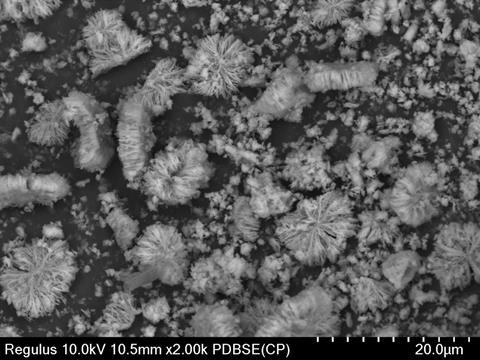

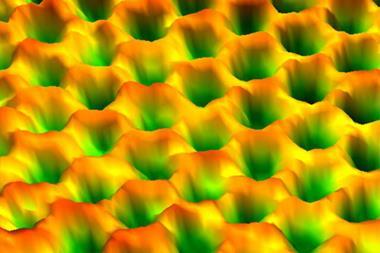

A few years ago, I was preparing a popular lecture for a wide audience. My goal was simple: to show the beauty of chemistry through images taken with an electron microscope. I remembered that in one of our projects, we had recorded truly stunning pictures of a metal-on-carbon catalyst with striking variations in morphology. The surface looked like a fantastic landscape from another planet – craters, valleys and mountains frozen in nanoscale. I thought this would be perfect material for my talk.

Naturally, I turned back to the article we had published on this catalyst. To my regret, only a handful of microscopy images were there – just enough to support the content of the paper. Where were the others? I checked my computer files, but nothing remained. I asked my co-authors to search their old folders, but again no luck. That was the dramatic moment: we realised we had lost these beautiful images. They had never been published, were not properly archived, and seemed to have simply vanished.

The lucky ending came when we dug into the storage system of the electron microscope itself. To our relief, everything was still there. But this episode left us with a haunting question: how much microscopy data is routinely lost to the wider scientific community?

A hidden universe of images

When we explored the microscope storage more carefully, we were astonished. Over a decade of work by many users had left behind more than 150,000 images. Each file was a frozen moment of exploration: nanoparticles scattered like stars, crystalline patterns resembling mountain ranges, catalytic supports stretching like cosmic deserts. The archive was like a universe in micro-space, breathtaking and scientifically meaningful.

Yet hardly anyone had ever seen most of these pictures. Except for the operator who pressed the button and the researchers who studied the sample, most of the images had never been revisited. This realization was the starting point of our research project: to quantify and analyse the phenomenon of ‘lost data’ in electron microscopy.

How much is lost?

On the storage, there were more than 150,000 electron microscopy images recorded over 10 years at our microscopy core facility. Yet we calculated that only about 3500 images – just over 2% – were published in peer-reviewed publications. In other words, more than 97% of recorded microscopy data never reached the scientific record.

Importantly, this loss was not due to poor image quality. The images were scientifically valid, often beautiful, and could easily provide insight. The main reason was practice: researchers tend to publish only a few ‘representative’ pictures that best fit the description of a paper. The rest are left behind.

Of course, the amount of lost data depends strongly on the operating policy of the facility and on the cost of the hardware. In our case, a multiple-user access system allowed independent researchers to collect as many images as they wished themselves. This encouraged creativity but also produced massive datasets that were never fully processed. At other facilities, where use is more restricted or expensive, the fraction of lost data might be lower. Overall, we estimate that it’s not uncommon for 50–90% of electron microscopy data to be lost. Even a 50% loss is still enormous.

Why it matters

Losing data on this scale has consequences. First, it represents wasted scientific opportunity. Expensive instruments generate information day and night, but most of it never enters the shared pool of knowledge. Second, it is a hidden inefficiency: the same experiments may be repeated elsewhere simply because the original data were never published. Third, it is a lost chance for inspiration. Many microscopy images are not only data but works of natural art – they can engage the public and attract young scientists.

Finally, in today’s world of artificial intelligence, large image datasets are of particular value. Machine learning methods thrive on scale: the more examples we provide, the better the algorithms can learn. By neglecting unpublished microscopy images, we miss the chance to accelerate AI-based discovery. What now lies dormant in forgotten folders could instead be the training ground for the next generation of scientific tools.

What can be done

Recognizing the problem is the first step. Our study highlights several practical directions to reduce data loss and unlock hidden value:

- Archive systematically: store all raw microscopy images with complete metadata, including acquisition conditions and sample details.

- Publish more broadly: make use of supplementary information and encourage journals to accept larger datasets.

- Create repositories: deposit microscopy images in open databases where they can be reused by others, with persistent identifiers such as DOIs.

- Use automation: apply machine learning to analyse, classify and annotate images, reducing the burden on researchers.

- Change culture: treat every high-quality image as a potential contribution to science, not just those that confirm a hypothesis.

These steps require some investment of time and resources, but the return is immense. Instead of being forgotten, microscopy images can fuel reproducibility, inspire collaborations and power data-driven research.

A closing reflection

When I finally gave my lecture, I was able to show those ‘lost’ catalyst images, and the audience reacted with delight. They saw what I had seen: a microcosmos of breathtaking landscapes revealed by electron beams. Thousands of similar images remain unseen in archives around the world.

We should not let this treasure slip away. Even if we cannot publish every image in a journal, we can preserve, share and reuse them. Lost data is not only a problem to be fixed – it is also a hidden resource waiting to be rediscovered. By valuing what we already have, we can open new doors for science, technology and human imagination.

References

N M Ivanova, A S Kashin and V P Ananikov, Chemistry, 2025, 7, 160 (DOI: 10.3390/chemistry7050160)

No comments yet