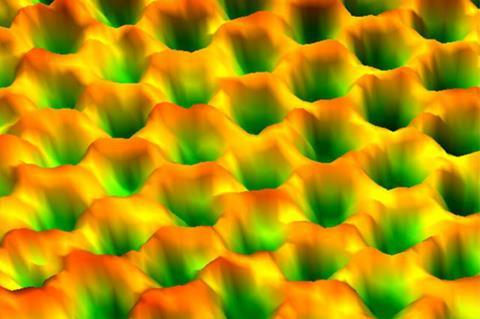

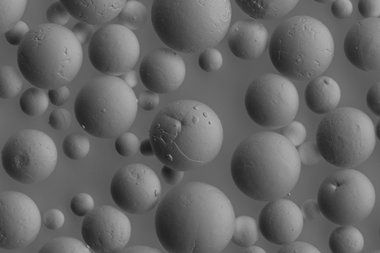

More than 97% of electron microscope images aren’t reported in peer-reviewed scientific papers, according to a large-scale analysis.

The authors of the study, analysed scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images produced at a single core facility for over a decade.

Out of the more than 152,000 evaluated images, the authors found that only just under 3600 (2%) made it into scientific papers. Specifically, only 2.6% of SEM images and 1.6% of TEM images were published in journals, meaning that the vast majority of microscopy data was lost.

Valentine Ananikov provides a personal perspective on how he’s trying to save the lost treasure of electron microscopy

‘Importantly, this loss is not due to poor quality,’ notes study co-author Valentine Ananikov, an organic chemist at the Zelinsky Institute of Organic Chemistry in Moscow, Russia. ‘The images were often excellent and scientifically informative, but only a few were chosen as “representative” illustrations for papers.’

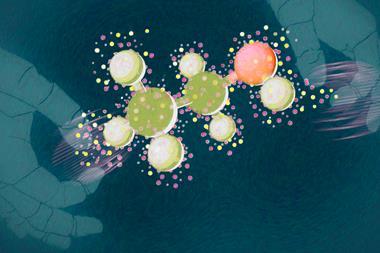

Ananikov says that the unpublished archive of diverse structures and scales is a ‘huge untapped resource’ in the age of artificial intelligence and data-driven research. ‘These unused datasets are exactly what AI systems need: large, varied collections of examples,’ he notes.

Researchers shouldn’t cherrypick images and publish the ones that fit the narrative of their paper, Ananikov says. Instead, they should archive all images systematically, which would make datasets more complete, he notes.

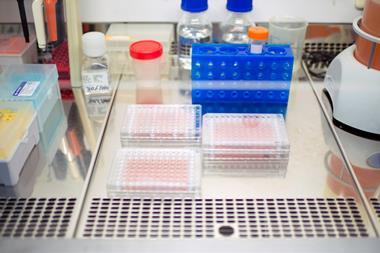

‘Sorting and annotating data manually was burdensome, but today’s tools can handle metadata and organisation efficiently,’ Ananikov says. ‘Another change would be fostering collaborative databases within the lab or across institutions, rather than leaving data scattered across personal computers.’

Reese Richardson, a metascience researcher at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, who was not involved with the new study, says it’s a problem that a lot of microscopy images go unused. ‘It’s very expensive to operate these instruments and to keep them going,’ he says. ‘I do think that a lot can be learned from these instruments and data.’

Richardson, however, thinks disciplinary norms and journal requirements are more often the reasons for images not making it to publication than authors being picky. ‘I always advocate to show as much as possible,’ he adds. ‘You don’t want to leave stuff out that could be potentially useful to other people. And after all, you’ve done the work anyway.’

Last year, Richardson co-authored a study that found that one in four research papers involving SEM instruments misidentifies which instrument was used, pointing to possible signs of misconduct. Metadata about specific instruments is often cropped out, Richardson notes, making it difficult to pinpoint specific equipment used in experiments.

Many repositories like the Electron Microscopy Public Image Archive and the Australian Antarctic Data Center Microscopy Database exist where researchers can post such images, Richardson says. ‘There’s a lot of options that exist now,’ he notes. ‘It’s just a matter of a culture change.’

In addition to preserving, archiving and annotating microscopy images systematically using AI and machine learning, it’s equally important to connect unused datasets to active research, Ananikov adds. ‘With proper analysis, hidden archives could reveal new patterns and accelerate discovery.’

References

N M Ivanova, A S Kashin and V P Ananikov, Chemistry, 2025, 7, 160 (DOI: 10.3390/chemistry7050160)

No comments yet