Large language models are powering a new generation of AI agents that could transform computational chemistry from a specialist discipline into one any researcher can use, reports Julia Robinson

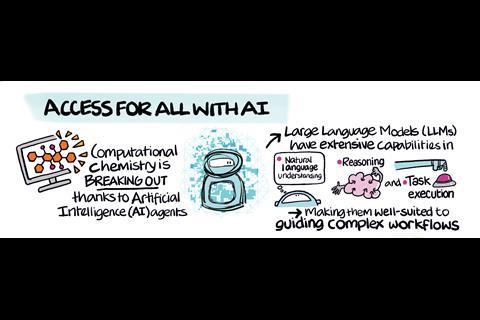

Computational chemistry is entering a new era. The rise of large language models (LLMs) has enabled the arrival of artificial intelligence (AI) ‘agents’ that could take the field from one reserved for specialists to one that’s open to anyone with an interest.

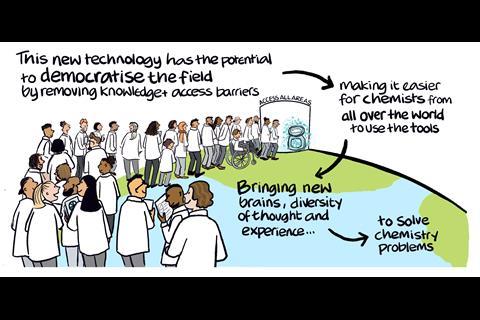

In 2025, several preprints were released showcasing new agentic frameworks for doing computational and quantum chemistry. Each of the teams developing these platforms has their own personal motivations, but one they all share is a desire to democratise the field.

‘The world always has two forces – elitism and democratisation,’ says Alán Aspuru-Guzik, a professor of chemistry and computer science at the University of Toronto in Canada, and co-director of the lab that developed the autonomous agent El Agente. ‘Why am I going to restrict computational chemistry to people that are trained to edit these – to be honest – archaic and horrible text files? Why is that? It is because people just follow tradition, they are not creative enough to rethink the entire system.’

Individual motivations

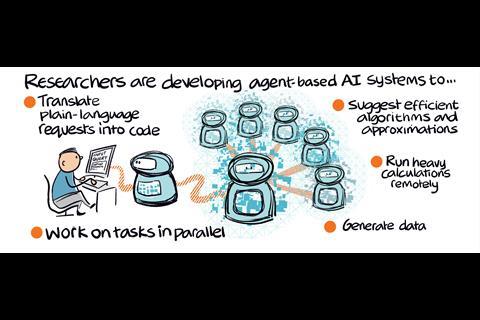

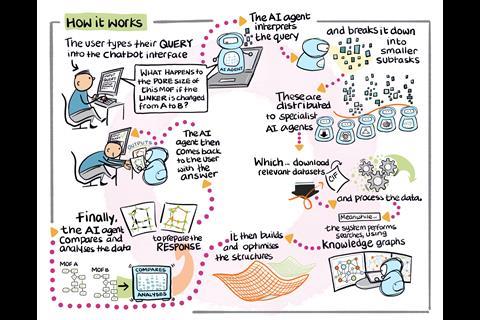

This new breed of AI agents works by conversing with users in their natural language to autonomously answer specific computational and quantum chemistry problems. The platforms can understand general scientific queries and are then able to break them down into steps, selecting the right tools and then solving them with minimal intervention by the user.

For some of the researchers developing them, their wish to make the field more widely accessible stems from barriers they faced as young researchers trying to break into computational chemistry.

Pavlo O Dral, a theoretical chemistry professor based at Xiamen University in China, and a lead researcher behind the AI-powered platform Aitomia, grew up in Ukraine, where resources were extremely limited – meaning he had to buy his own computer in order to start learning computational chemistry. ‘It was not state of the art,’ he says.

Aitomia

Team: Nine researchers led by Pavlo O Dral at Xiamen University in China.

Status: Publicly available since 11 May 2025.

What it does: Aitomia assists researchers in all stages of their work, from setting up the calculations, providing possible options, automatically performing the simulations, and then helping to analyse the results in an understandable and reusable format. It supports a wide-array of AI-driven atomistic and quantum chemistry methods enabling essential computations such as energy calculations, geometry optimisations, molecular dynamics, thermochemistry, reaction and spectra simulations.

‘Under the hood, we don’t use pure quantum mechanical methods,’ explains Dral. ‘We use our machine learning models, trained on lots of quantum mechanical data, so it is producing these results with high accuracy, but because it’s machine learning, it’s also very, very fast.’

Example user query: Calculate the thermodynamic properties of the Diels–Alder reaction between ethene and 1,3-butadiene.

Dral describes the gap between research groups that have access to abundant resources and those that don’t as ‘a big problem’. ‘If the group has lots of resources, they can do the state-of-the-art science … if you are a small group, in a not very rich environment, it’s a big obstacle,’ he adds.

Varinia Bernales, an assistant professor at the University of Toronto in Canada, who co-directs the lab behind El Agente with Aspuru-Guzik, faced a significant language barrier in her home country of Chile. ‘It’s a small country, English is not a primary language … we were isolated by the natural geography … so it was rough,’ she recalls. ‘At the university level, it was a struggle to even read books in English … I had to email people to get papers, I struggled to read them, so it took me a long time.’

Having the right resources, doesn’t necessarily make computational chemistry easier to master.

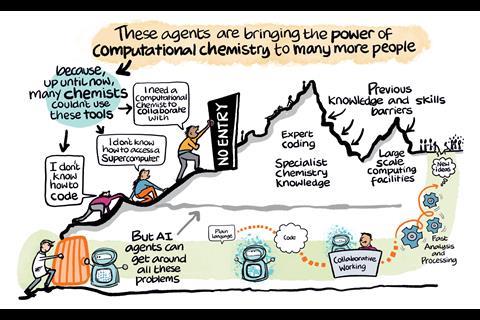

Chemists often spend years getting to grips with the necessary software and building the expertise required to navigate a vast and increasingly sophisticated array of tools, as well as to interpret results accurately. Many workflows also depend on high-performance computing (HPC) resources, which are not readily available to experimental chemists and students.

Computational chemistry … is not impacting chemistry research as much as it could and one reason for that is the difficulty in applying the vast array of tools, which often demands expert knowledge and substantial computational resources

Some suggest that this high barrier to entry may be slowing innovation in fields like drug discovery and materials science. ‘If you look at materials simulation and discovery, people spend a very long time – maybe two or three years – spending all of their effort figuring out how to run even one calculation that is high quality; it’s pretty time consuming,’ says Venkat Viswanathan, an expert in mechanical and aerospace engineering at the University of Michigan, US and one of the researchers working on the Density Functional Theory (DFT)-based Research Engine for Agentic Materials Screening (Dreams).

‘Computational chemistry has evolved a lot,’ says Murat Keçeli, a computational scientist at Argonne National Laboratory in the US, and one of the developers of the agentic framework ChemGraph. ‘However, it is not impacting chemistry research as much as it could and one reason for that is the difficulty in applying the vast array of tools, which often demands expert knowledge and substantial computational resources.’

El Agente, Aitomia, ChemGraph and Dreams are four agentic frameworks poised to transform the way we do computational and quantum chemistry.

‘Our motivation with this ChemGraph agent was to simplify the job of anyone who is trying to use computational chemistry tools – not just the basic ones, but even the state-of-the-art methods,’ says Keçeli.

The rise of the agent

One of the biggest factors in why these next-generation agentic models are now popping up is the advent of LLMs such as ChatGPT and DeepSeek. LLMs have demonstrated extensive capabilities in natural language understanding, reasoning and task execution, making them well-suited for guiding complex workflows.

‘Agents have been around since the 1990s, but they were rule-based systems,’ explains Bernales. ‘What makes the difference now is the LLMs powering these agents.’

Keçeli explains that LLMs help to create a natural language or ‘chat’ interface, which, he says, is going to become the norm for all computational chemistry programme. ‘Our main task should be [to] get rid of this barrier about the domain specific or the program specific syntax that one needs to learn – it can all be generalised into natural language interface thanks to LLMs.’

ChemGraph

Team: Three core members led by Murat Keçeli at Argonne National Laboratory in the US, with input from 10+ collaborators worldwide.

Status: Code available via GitHub.

What it does: ChemGraph combines natural language processing with machine learning potentials, to perform a series of computational chemistry tasks ranging from SMILES string and molecular structure generation to geometry optimisation, vibrational analysis and thermochemistry calculations.

‘Our target is that anyone who has an interest to learn about computational chemistry should be able to use it,’ says Keçeli. ‘We have a more developer-centric command line interface, but we also have a graphical user interface, and that graphical user interface is easily manageable by even an undergraduate student who wants to learn about computational chemistry.’

Example user query: Calculate the reaction enthalpy using MACE-MP at 400K for the methane combustion reaction.

For Viswanathan and his team, one of the main elements they found to be crucial for the development of Dreams was the emergence of AI reasoning models. ‘AI reasoning models are critical to be able to plan these sorts of complicated tasks, otherwise, you could do some simple things, but then it would get stuck doing anything sophisticated.’

Overall, he explains that agentic tools have come on leaps and bounds over the past year. ‘If you told me a year ago that we could do this, I would have said, “No way!”. It’s truly extraordinary times – those that can use it, it’s certainly like they have a superpower.’

Another development Keçeli says has been key to ChemGraph, that has been going on for the past 10–15 years, is that of machine learning interatomic potentials. ‘AI brought the computational chemistry world a huge technological breakthrough in the sense that you don’t need to solve the Schrödinger equation all the time – this is the most time-consuming part in all quantum chemistry.

‘What interatomic potentials are bringing us is if you already have a data set that is composed of high accuracy calculations and then you train your machine learning method on that you will be able to use that instead of solving the Schrödinger equation by yourself.’

Overall, Bernales says that there has also been a shift in the perception of computational chemistry, an evolution she says she has experienced first-hand. ‘From my early days as an undergrad, when people didn’t trust computational results at all, to my time at Dow Chemical, where my role was to enable catalyst discovery using techniques now considered fairly standard.

‘This … of course, [has] been made possible by … computational efficiency enabled by hardware and accessibility, significantly benefitted by the cultural shift toward open source, which includes code, publications and dissemination venues.’

The developers of all four platforms hope to open the field to just about anyone who has an interest in computational chemistry, without requiring users to have formal training in the field. And the beauty of AI systems means that the platforms will be constantly upgraded to improve and widen the user experience.

‘At the beginning it’s going to be computational chemists, then any chemist, then any human, of any age, for any reason,’ says Aspuru-Guzik. ‘El Agente should be the place that you go and talk about chemistry and material science. And this can be done, there’s agents now that do all sorts of things for you. Our agent is just going to be the chemistry agent.’

Challenges along the way

Of course, as is the way when paving a new path, every team has experienced roadblocks along their journey. And, with AI evolving so fast, challenges are often solved as rapidly as new ones arise.

For ChemGraph, a major problem the team has faced is the cost of the models and, as a result, they have been working to reduce this as much as possible, without it limiting the capabilities of the platform. ‘This is why we are not advocating the single agent framework but a multi-agent framework with different agents; smaller language models can do simpler tasks, [then] if you want to have more reasoning, you can have a large language model in certain tasks,’ explains Keçeli. ‘By combining this, we will reduce the number of token usage for the large language models and reduce the cost significantly.’

Dreams

Team: A team of five at the University of Michigan in the US led by Venkat Viswanathan.

Status: Code available via GitHub.

What it does: Dreams is a multi-agent framework for DFT simulation that combines a central LLM planner agent with domain-specific LLM agents for atomistic structure generation, systematic DFT convergence testing, HPC scheduling, and error handling. A shared canvas helps the LLM agents to structure their discussions, preserve context and prevent hallucinations. The researchers describe it as a ‘scalable path toward democratised, high-throughput, high-fidelity computational materials discovery’.

‘It’s an all-knowing foundation model that can orchestrate tasks that are of a computational nature,’ says Viswanathan. ‘It has a computational agent that knows how to run codes, it has an HPC cluster agent that knows how much computing resources are needed, how much time, how much memory. Then you have a validation agent that decides whether it’s at the right level of accuracy.’

Example user query: What is the lattice constant for lithium cobalt oxide in the layered structure?

For other groups there were issues with precision and hallucinations – where incorrect information is presented as fact – requiring them to make tweaks as they went along, sometimes even having to write tools over from scratch.

‘The problem with a large language model is maybe 99% is fine, but occasionally, for that 1%, it will do it incorrectly,’ says Viswanathan. ‘But, in science, you can’t have that 1%.’

Aspuru-Guzik says the challenges and problems keep on coming, but as they fix them the platform is also getting better. ‘It used to be like an undergraduate, now it’s almost like a grad student. But when we release it, we want it to be like as good as possible,’ he explains. ‘What is cool about our group is that we’re building a lot of tools at the research level, and we’re going to start adding them to El Agente as we go along. At launch we will have surprises!’

The future of computational chemistry

The teams all have their own thoughts on the future of computational chemistry and how their platforms will contribute towards that.

Keçeli’s wants experimental chemists to use ChemGraph to independently tackle problems they might otherwise hesitate to ask others about. ‘I am hoping that when they can access the tools in an easy way, they will be solving important problems more quickly,’ he adds.

This aspiration is shared by Aspuru-Guzik, who hopes El Agente will help experimentalists in their day-to-day research, producing reliable results that are trusted. However, long term he is excited to see how the platform develops into a smarter version of itself and, ultimately, become ‘an agent of good in society’. ‘We have this cool feature that we want to have before we launch that, every time you finish, it will tell you, “Oh, you just calculated this molecule. Do you want to know more about it in terms of safety?”.

‘The ultimate future is a network of agents talking to each other, so our agent can talk to all the other agents,’ says Aspuru-Guzik. And this isn’t just about a network of agents exclusive to one platform, Bernales says one of their goals is to have a community in which all the platforms – Dreams, Aitomia, ChemGraph and El Agente and others – can work together. ‘Why not integrate these and make it in a way that everyone can contribute in different ways?’ she asks.

Viswanathan agrees, noting that connecting these parallel efforts, and potentially even integrating them with autonomous labs – which are also developing in their capabilities – could significantly accelerate innovation in materials science. ‘If you invented a new material, the timescale from that invention for it to reach commercialisation, it’s roughly 18 years on average, across disciplines. So, the goal is that this can shrink it down dramatically,’ he says.

DFT is not dead yet, but DFT is forever transformed by the agents, because you will not do DFT anymore by writing an input file, you’ll do DFT by talking in your native language – DFT is democratised … DFT is for the people

Although, when it comes to AI there are important considerations to be made around sustainability – something Aspuru-Guzik says ‘keeps him up at night’. He believes El Agente has a responsibility to tell users how much carbon dioxide their query is using, but points out that users should also be more conscious of how they use AI in general. ‘The question is, do you want to use ChatGPT to generate [something] silly or stupid? I argue simulating a molecule for your research is much more important than that. Like always with supercomputing, it’s what you use it for that matters.’

Viswanathan says it is important for these platforms to be as computationally efficient as possible but points out that computational chemistry in general is extremely power-hungry. ‘All of the supercomputers in Europe, all the supercomputers in North America, about 30 to 40% is run just for either DFT calculations or quantum chemistry calculations,’ he says. ‘Suddenly if you put agentic workflows in there – that balloons the amount of resources that it’s using.’

El Agente

Team: About 27 researchers at the University of Toronto in Canada, led by Alán Aspuru-Guzik and Varinia Bernales.

Status: In alpha testing.

How it works: El Agente employs a hierarchical network of specialised LLM-based agents, each equipped with an extensive list of available tools. This hierarchy effectively filters out the irrelevant context for each agent, significantly enhancing the decision-making performance of the entire system, enabling complex planning and task execution via feedback loops.

‘We are aiming to have a scientist that can get to the point that it can generate and validate hypotheses and work with you in the lab,’ says Bernales. ‘What differentiates us from the others is that we have a level of autonomy, adaptability, error, recovery, troubleshooting, a lot of things that basically don’t need human intervention. We have an interactive mode where you can intervene, or if you want the agent to do the entire work and do it right then it can.’

Example user query: Generate and optimise key intermediates in CO2 reduction on a given organometallic catalyst, tracking how bonding and charge evolve along the reaction path.

However, as more people turn to AI to do quantum chemistry this could improve the overall efficiency of their workflows. With the growth of this approach, some researchers are even declaring the death of DFT – although Aspuru-Guzik disagrees. ‘DFT is not dead yet, but DFT is forever transformed by the agents, because you will not do DFT anymore by writing an input file, you’ll do DFT by talking in your native language – DFT is democratised … DFT is for the people.’

Dral explains that smaller LLMs, that run on small commodity hardware and therefore use a lot less energy, are becoming more capable of carrying out complex workflows so there might be the option for them to switch over in the future, helping to reduce their carbon footprint.

‘Every month there are newer, better models – the previous models, which we tested last year, they were not very good, so we switched back to the full model,’ he explains. ‘But now, the newest models, which appear are increasingly better … it’s not that much more in terms of electricity consumption compared to a typical desktop computer.’

Another issue is that of security and safety and the tension between wanting openness and transparency but also not wanting the platform to be open to abuse. For El Agente, this means not releasing the code, at least for now. This has the added benefit of enabling them to modify the code as they go. ‘It gives us an opportunity to experiment without people seeing our dirty code,’ says Aspuru-Guzik. ‘Once we’re ready, we’ll release pieces of it.’

For Keçeli, safety is also about ensuring that the tools are working as accurately and reliably as possible. ‘Wasting people’s time is also harming the research – these are scientists who are going to use your tool, and their time is valuable … evaluating the performance of whatever AI technology you are using for real use cases, is very important.’

While it is early days for these platforms it will be interesting to see how they impact the field of computational chemistry, from the number of people entering the field who may not have done so before, to the effect it could have on research and materials discovery.

‘If someone says, “Because of El Agente, I am interested in quantum chemistry” … If El Agente can do that for one person, that’s the impact,’ says Aspuru-Guzik. ‘We just need one anecdote, one person.’

While we’ll have to wait to find that out, it’s clear that significant change is already afoot. ‘I’m pretty sure that in the future, people will wonder how people previously did quantum chemical simulations,’ says Dral. ‘Like we are now astonished at how people built the pyramids in Egypt.’

No comments yet