In November 2023, the UK became the first country in the world to authorise a Crispr gene-editing therapy.

Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel) is for patients with debilitating forms of sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent β-thalassaemia – both of which are caused by errors in genes that code for haemoglobin – a protein found in red blood cells which carries oxygen around the body.

But how is the world’s first Crispr-based treatment performing in UK patients so far?

How does Casgevy work?

Both sickle cell disease and β-thalassaemia are caused by errors in the genes that encode haemoglobin. In sickle cell disease the effect of this is that red blood cells are misshapen and sticky, causing them to form clumps that clog blood vessels, reducing oxygen supply to tissues resulting in periods of extreme pain.

It’s a nice product, it’s clever and it’s good science

David Rees, King’s College London

In β-thalassaemia the mutation leads to low levels of haemoglobin in the blood and a reduced number of red blood cells causing symptoms such as fatigue, shortness of breath and an irregular heartbeat. Patients often need a blood transfusion every three to five weeks. β-thalassaemia affects around 1000 people in the UK, while sickle cell is the UK’s biggest genetic blood condition, affecting around 17,000 people. ‘For a “rare disorder” it’s a really big condition – it predominantly affects people whose heritage is from Africa [and] the Caribbean,’ says John James, chief executive of the Sickle Cell Society. ‘But it affects [other] people of colour and mixed heritage as well.’

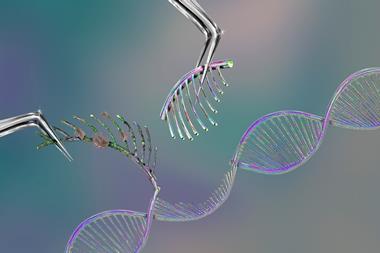

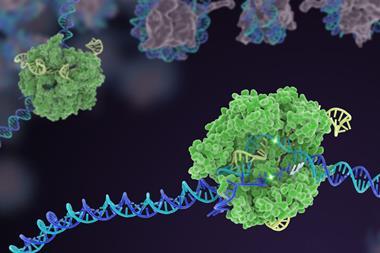

Casgevy, manufactured by Vertex Pharmaceuticals and Crispr Therapeutics, uses the innovative gene-editing tool Crispr–Cas9 to inactivate the BCL11A gene that usually prevents the production of a form of haemoglobin that is only made by foetuses.

The Cas9 enzyme is guided by an RNA molecule to the correct region of DNA where it cuts both strands. By disrupting the gene, Casgevy enables the production of foetal haemoglobin, which does not carry the same abnormalities as adult haemoglobin in people with either sickle cell or β-thalassaemia.

The treatment performed well in trials and 97% of patients with sickle cell disease were free of serious episodes of pain for a year after (although only two-thirds of the 45 patients were in the trial long enough to be included in this specific analysis). In the case of β-thalassaemia, 93% of trial participants didn’t need a transfusion for at least 12 months.

Approval delays

Despite the prevalence of these conditions there is a distinct paucity of treatments available. And even in the case of Casgevy, the incredibly high list price – £1.65 million per patient (although the NHS has reportedly negotiated a discount) – initially held back its approval in the UK. In March 2024, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice), which examines treatments on a cost-effectiveness basis, withheld approval in draft guidance, saying that more information was needed.

Nice eventually revised its decision in September 2024, approving the use of Casgevy to treat patients over the age of 12 with β-thalassaemia and then, at the beginning of 2025, its use as a treatment for patients over the age of 12 with severe forms of sickle cell disease.

‘It was hard to convince Nice to approve Casgevy for sickle cell,’ says Fred Piel, a leading expert in the epidemiology and health burden of sickle cell disease and other blood disorders, based at Imperial College London, UK. ‘It’s been reviewed three times; the critical element in that decision the third time around was input from patients and members of the community about the impact [the disease] had on their daily lives,’ he adds.

The treatment is now being offered under a managed access scheme in the UK to enable further data to be collected on its long-term effectiveness. As a result, it was initially estimated that only around 50 of the approximately 18,000 people living with sickle cell disease and β-thalassaemia in the UK, who were suitable for a stem cell transplant but without a matched donor, would receive the treatment each year. Experts suggest the number so far this year may be considerably lower.

There is also a lot of misconception about what the treatment involves … in practice, it’s quite brutal … it’s a painful process

Fred Piel, Imperial College London

The announcement of the drug’s approval was met with something of a mixed response. ‘The way it was presented as a new curative magic treatment was very positive,’ says David Rees, a paediatric haematologist at King’s College London and King’s College Hospital, UK. ‘It was presented in widespread media in a very positive way, and that’s nice for patients.’

‘Amongst doctors, there was a mixed reaction. People acknowledge it’s good that there’s another treatment, but there are problems with it.’

Piel says there is something of a ‘disconnect’ between the hype around Casgevy in the media and the reality for most patients, which is that it will probably not be accessible to them. He highlights that for a long time there have been significant issues with ‘racism, inequalities, poor awareness of the condition or understanding of their complications’, leading to many patients falling between the cracks and losing trust in the system set up to support them.

Although there are a number of treatments that help patients with the symptoms of sickle cell disease – which include episodes of severe pain, chronic tiredness and frequent infections – in terms of disease-modifying treatments, aside from Casgevy, there is really only one: hydroxyurea, also known as hydrocarbamide, which is taken orally daily.

In the last few years, sickle cell patients have seen two promising treatments appear and then subsequently withdrawn – Adakveo (crizanlizumab) and Oxbryta (voxelotor). As a result, James says that although many patients welcomed the news of Casgevy, they did so cautiously. ‘Primarily the community that is seeking effective treatments are distrustful of new treatments … That community will have seen two treatments [come through] and generally, there will be scepticism.’

James adds that there is also reticence because of the nature of the treatment. ‘This isn’t a simple tablet – you have to go through quite a challenging process of transplant, and it’s not without risks,’ he adds.

Piel agrees: ‘There is a lot of misconception about what the treatment involves … in practice, it’s quite brutal … it’s a painful process,’ he adds.

Casgevy in the clinic

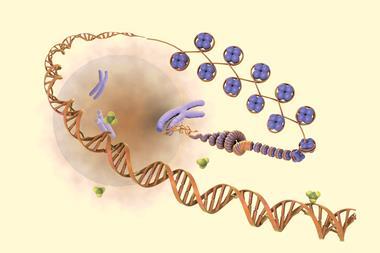

To carry out gene editing using Casgevy, clinicians need to first take stem cells from the bone marrow of the patient. Then, after editing, but before they are reintroduced back into the body, patients undergo ‘conditioning’ to wipe out their immune system and prepare the bone marrow before the modified cells are infused back into the patient.

This isn’t a simple tablet – you have to go through quite a challenging process

John James, Sickle Cell Society

Patients may need to spend at least a month in hospital while the edited cells are incorporated into the bone marrow and start to make red blood cells containing normal, foetal haemoglobin.

The side effects from the treatment are like those associated with stem cell transplants, including nausea, fatigue, fever and increased risk of infection. However, Rees says the chemotherapy required for the Casgevy conditioning process is, in fact, more toxic than that used for many types of stem cell transplants in that it includes busulfan, a potent alkylating agent. ‘A small percentage of patients have died because of the chemotherapy,’ he explains. ‘You’re also infertile or at least sub-fertile following that.’

He adds that there are also concerns about whether the editing process, in the long term, increases the risk of cancer. ‘It’s still a bit uncertain … it seems to be very targeted [but] there’s some editing that goes on in areas that you don’t want it to.’

‘Then you’re repopulating someone’s bone marrow for the rest of their life, which might be 70 or 80 years, with a very small number of stem cells that potentially makes it more likely that they’ll develop clonal disorders and problems in the future.’

He adds that Casgevy is also not completely curative. ‘It doesn’t cure sickle, it ameliorates it, and reduces the symptoms, and seems quite effective at doing that. But people still have sickle cell disease, they just have a much milder form of it … some people on hydroxycarbamide get pretty much the same effect.’

The treatment is currently offered at only seven specialist NHS centres in London, Manchester and Birmingham, which is an issue for patients who live further afield. ‘If you move outside of those areas covered by specialist centres, often you find a total lack of knowledge or awareness of sickle cell disease,’ says Piel.

The beginning of the story

James says he’s aware of referrals coming in from all over the country to the national panel who decide which patients are suitable for treatment with Casgevy. ‘I know of individuals who have gone through the process,’ he says. ‘From the non-identifiable data [available], the numbers are going up.’ However, he highlights the importance of good psychological support to help patients with the high emotional fallout of the treatment. ‘There’s no point approving a transplant centre who doesn’t have a good backup of red cell psychology services,’ he says.

NHS England was approached for comment on the number of patients that have received Casgevy since its approval but no response was received.

King’s College Hospital, where Rees works, is one of the specialist centres, but he says that, so far, they haven’t treated any patients. Overall, he admits he might be more negative about the treatment than others, but he says he believes this is just the beginning of the story for sickle cell treatment. ‘It’s a nice product, it’s clever and it’s good science, but … it’s not like it’s so good you can’t imagine anything better.’

He thinks that in vivo gene editing will be the next step. ‘You just inject, like a vaccine, the editor directly into the person, and it finds their stem cells, and edits them. It’s simple, almost like an outpatient procedure,’ he explains. ‘That’s where the end of this is.’

Piel thinks it’s too early to say what impact Casgevy will have on patients in the UK, particularly as it is not clear yet how many patients have received it so far. But, he says that the spotlight on the new treatment has brought with it an important recognition of the impact these conditions have on patients on a day-to-day basis, which has been helpful for the community.

‘That is a positive, even if, so far in the last year, probably the number of people who have received Casgevy, I would guess, is a lot smaller than the 50 talked about.’

James says the reality is that the unmet need for these patients is ‘still huge’. ‘We want to see a lot more innovation and development in industry to have a wider choice of treatments for professionals and patients,’ he adds.

No comments yet