The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has finalised a ban that prohibits the use of chrysotile asbestos, which is still used and imported into the US. This action, taken under the Toxic Substances Control Act (Tsca), follows decades of unsuccessful attempts by lawmakers and health advocacy groups to ban asbestos in the US.

‘The science is clear – asbestos is a known carcinogen that has severe impacts on public health,’ stated EPA Administrator Michael Regan in the 18 March announcement. ‘That’s why EPA is so proud to finalise this long-needed ban on ongoing uses of asbestos.’

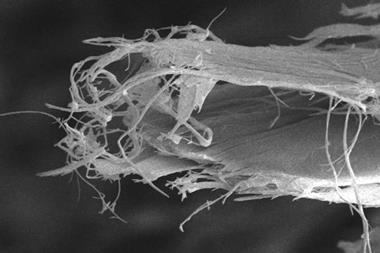

Most consumer products containing chrysotile asbestos have been discontinued, but raw chrysotile asbestos was imported into the US as recently as 2022 for use by the chlor-alkali industry. It is found in products like asbestos diaphragms, sheet gaskets and vehicle brake pads.

A couple of years ago, the US chemical industry pushed back against calls to implement an outright ban on asbestos, similar to those enacted by the UK and more than 50 other countries around the world.

The new ban only addresses one of six asbestos fibres, and it just applies to six applications. Advocacy groups like the Asbestos Disease Awareness Organization suggest that this leaves the door open to other types of asbestos.

Under the EPA’s new prohibition, the eight chlor-alkali facilities in the US that still use asbestos will have to transition to either non-asbestos diaphragms or to non-asbestos membrane technology. The final rule ensures that six of the eight will complete this transition within five years, with the remaining two to follow.

Phase-out periods

The agency acknowledges that converting facilities is not easy. Therefore, it specifies a five-year transition period for companies to convert their first facility to non-asbestos membrane technology, eight years to convert their second and 12 years to convert their third.

‘The EPA has been seeking to ban and or limit the many uses for asbestos since the 1980s, and this rule is trying to continue with that and close the gaps on most of the remaining uses out there,’ explains Lynn Kornfeld, an environmental partner at the law firm Holland & Hart. ‘This is a ban on common uses that are still out there.’

The American Chemistry Council, a trade group representing US chemical companies, views components of the final rule as positive changes but still has some significant concerns. The organisation said the EPA’s inclusion of these incremental phase-out periods will help to minimise unnecessary service disruptions at plants, but it remains apprehensive about the agency’s approach to developing existing exposure limits in occupational settings. In the past, the ACC has argued that chrysotile asbestos diaphragm technology is being used safely by the chlor-alkali industry.

Meanwhile, the International Chrysotile Association has made the case that chrysotile asbestos is safe if proper procedures are followed for its use, and it has suggested that if it is banned that would lead to an increased use of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) whose impact on human health and the environment, as well as on the chlor-alkali industry, have not yet been scientifically assessed.

But further asbestos regulatory changes could soon be underway in the US. The EPA says it is evaluating other types of asbestos fibres separately, in addition to legacy uses and associated disposal of chrysotile and asbestos-containing talc, and the agency will address those items in an upcoming risk evaluation. An EPA draft risk evaluation is expected to be released soon, and the agency plans to publish the final risk evaluation by 1 December.

No comments yet