A drop in atmospheric pollution during the Covid-19 pandemic drove a surge in methane in the early 2020s, a new study finds. A sharp decline in hydroxy radicals – formed from carbon monoxide and oxides of nitrogen (NOx) – halted the atmosphere’s ability to break down methane, accounting for around 80% of the methane spike. This is much larger than previous estimates and highlights that increased methane emissions form only part of the picture.

Methane levels in the atmosphere grew at over 16 parts per billion per year between 2020 and 2022, double the rate of increase in the years either side of the surge. Researchers previously suggested that the combination of an increase in natural methane emissions and fewer hydroxy radicals in the atmosphere drove the sharp increase,1 with each contributing equally. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas with a warming potential that is around 30 times greater than carbon dioxide over a 100 year period.

However, an international team has now reported that the atmosphere’s weakened ability to break down methane during these years was the main culprit behind the spike in methane.2

Shushi Peng at Peking University in China explains that the Covid-19 pandemic – which coincided with the surge in methane – led to falling emissions from industry and travel. This reduced overall levels of carbon monoxide and oxides of nitrogen in the atmosphere, which are precursors to hydroxy radicals. These short-lived radicals oxidise methane into carbon dioxide and water, meaning the atmosphere removed methane at a slower rate during the pandemic.

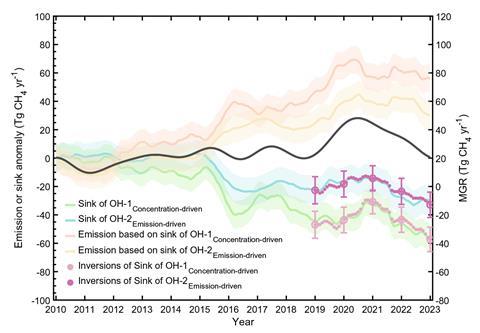

The team modelled hydroxy radical levels between 2019 and 2022 and combined this with data collected by satellites that measured radical precursors such as ozone, carbon monoxide and NOX.

Analysis revealed that the weakened methane sink provided by hydroxy radicals may account for around 80% of the year-to-year variation in the growth rates of methane in the early 2020s, with increased emissions from wetlands and agriculture accounting for the rest.

Chris Wilson, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Leeds in the UK, who was not involved in the work, explains that ‘there’s a really complex mix of driving factors which led to the changes in the early 2020s’. ‘Because sinks of methane are quite difficult to measure and to understand, we might have been a bit guilty prior to 2020 of not quantifying their effects as much as we should be.’

The hydroxy radical methane sink returned in 2023 after the Covid-19 pandemic due to increased NOx and carbon monoxide emissions. However, Wilson says this does not mean that efforts to reduce these pollutants should halt, as ‘NOx emissions are responsible for tens of thousands of deaths a year’.

Wetter weather during a La Niña event between 2020 and 2023 also caused wetland areas to expand and release more methane. ‘[However], we still have problems estimating wetland methane emissions,’ says Peng, explaining that there is a discrepancy in annual methane emissions between models. Better monitoring of flooded areas and water-table changes may improve such models and provide better insight into year-on-year variations in methane.

References

1 S Peng et al, Nature, 2022, 612, 477 (DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-05447-w)

2 P Ciais et al, Science, 2026, DOI: 10.1126/science.adx8262

No comments yet