Natural and anthropogenic organic molecules can both spontaneously self-assemble into supramolecular atmospheric nanoparticles during heat waves, research from the US has shown.1 The work, which explains high levels of new particle formation during hot weather, could inform climate change models and help explain the death tolls associated with extreme heat events.

Clouds can both reflect heat to outer space and trap it in the Earth’s atmosphere making them one of the most important feedbacks in climate change models, and the single most uncertain. Cloud formation requires nucleation of gaseous water molecules with acids. Around half of these are thought to be seeded by new particles like oxidised pollutants such as sulfur dioxide or volatile organic compounds in the lower atmosphere. Heat waves should naïvely be expected to cause increased evaporation of volatile organic compounds, reducing new particle formation, but this has not been well studied.

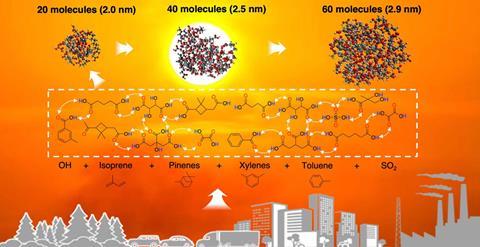

In 2004, a study by led by Renyi Zhang at Texas A&M University suggested that organic acids – produced when sunlight oxidises either natural volatile organic organic compounds such as pinene from trees or aromatic hydrocarbons from car engines – could form unusually stable complexes with sulfates in polluted air, enhancing aerosol production.2 The researchers have subsequently developed techniques allowing mass spectrometry of atmospheric particles as small as 3nm – around 60 molecules in total.

In their new work, they unveil measurements recorded over the course of a month on the Texas A&M campus. Some of the strongest new particle formation occurred when the temperature was well above 30°C. Sulfuric acid was only present in small amounts, suggesting that organic acids could not only form complexes with sulfuric acid, but they could self-assemble into nanoparticles on their own. ‘Organic acids can form a double hydrogen bond, which is very stable, and there’s multiple branches for them to grow,’ explains Zhang. ‘We believe that, if that’s happening here, it’s also happening in other places.’

The spontaneous assembly mechanism is not constrained by the volatility of the organic compounds, so Zhang believes it provides a natural explanation for high-temperature new particle formation. Questions remain about the extent and direction of the feedback that the very small, entirely-organic particles might have on climate change, as they are unlikely to be highly hygroscopic. This could prevent them seeding aerosols that produce clouds. They could have other implications, however. ‘People die of heat waves, and the ultrafine particles can get very deep into your bodies,’ says Zhang. ‘The smallest particles are exclusively organic acids… More work needs to be done on how heat combined with these ultrafine particles impacts human health.’

‘It’s exciting that they are seeing new particle formation so often at such high temperatures,’ says Hamish Gordon of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, US. ‘In a chemistry sense, hydrogen bonding of molecules is probably involved when any nanoparticle is formed in the atmosphere, so that part isn’t new, but nevertheless the results are interesting.’

References

1 R Zhang et al, Science, 2026, DOI: 10.1126/science.ady5192

2 R Zhang et al, Science, 2004, 304, 1487 (DOI: 10.1126/science.1095139)

No comments yet