Scientific expertise at the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) took a huge hit over the past four years of Donald Trump’s administration, with the agency losing 672 such posts between 2016 and 2020, according to an analysis by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS). In 2018, the EPA’s total workforce was down by 21% compared with its all-time staffing peak in 2000.

From 2016 to 2020, more than 560 environmental protection specialists working on environmental defence and pollution control programmes left the agency. 125 jobs were lost in environmental engineering, 44 in chemistry, 15 in chemical engineering and 18 in microbiology, the UCS found.

‘The numbers are devastating, it is extremely unusual as far as I am aware,’ says Christine Todd Whitman, who led the EPA under former President George W Bush, and now runs an environment and energy consultancy specialising in government relations. ‘You have lost not just raw science and raw chemistry capacity, but also the institutional knowledge about how the agency works and the regulatory requirements,’ adds Whitman, who is also the former Republican governor of New Jersey.

Earlier this month, the EPA rejected the Trump administration’s actions that weakened the agency’s health assessment for perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS), which was issued the day before Biden’s inauguration. Animal and lab studies have linked even low levels of PFBS exposure with thyroid, kidney and reproductive problems, as well as developmental effects and immunosuppression.

Scientists at the EPA have reviewed the content of that 19 January PFBS Toxicity Assessment, and have made an initial determination that its conclusions were ‘compromised by political interference as well as infringement of authorship and the scientific independence of the authors’ conclusions’. After concluding that this constitutes a violation of the EPA’s scientific integrity policy, the PFBS documents have been removed from the EPA’s website while its review is completed.

Under Trump, Whitman says there were ‘four years of science being denigrated and set aside for political reasons’. At one point, the EPA was down about 800 scientists or more, she notes. ‘While you want some new blood, many of those who were hired to replace the scientists who left came from the very industries that the agency oversees,’ Whitman recalls. She says many scientists departed the agency because they felt their work was not being valued, and that they couldn’t speak freely.

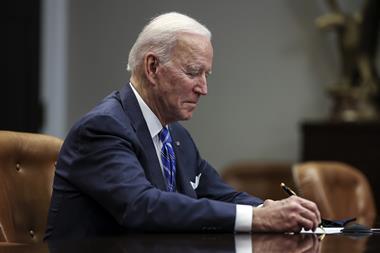

President Joe Biden has made it clear that science is a priority in his administration, but Whitman suggests that it could take a while to recruit the necessary expertise. ‘[Scientists] know that under this administration it will be good, but in four years, who knows? Building back trust is going to be very difficult,’ she says.

No comments yet