All primates given ZMapp are cured of Ebola but the drug is still a long way from approval in humans

In the hunt for a treatment for Ebola, a new study has shown that monkeys given the experimental drug ZMapp all survived infection with the virus.1 The trial further bolsters ZMapp’s reputation after two US healthcare workers with Ebola recently left hospital after taking the drug, the first Ebola patients to be treated in the US. The therapy does, however, still require safety testing in humans before it is likely to be given to large numbers of Ebola patients.

In the trial, Rhesus macaques were infected with Ebola and given three doses of ZMapp, administered at three-day intervals. The treatment reversed severe symptoms such as excessive bleeding, rashes and elevated liver enzymes, report the authors from the Public Health Agency of Canada. Three rhesus macaques that did not receive ZMapp succumbed to the disease.

For monkeys, receiving the drug up to five days after infection is a relatively late stage in the infection. ‘The level of improvement was beyond my own expectation,’ says author Gary Kobinger. ‘I was quite surprised that the best combination would rescue animals as far as day five, it was fantastic news. What was very exceptional is that we could rescue some of the animals that had advanced disease. This is a huge step forward compared to previous antibody combinations.’

The course of Ebola is slower in humans than macaques with an incubation period that can last up to 21 days. Estimates are that ZMapp may be effective as late as day nine or 11 after infection. However, Kobinger stresses that there is ‘a point of no return’ where there is too much damage to major organs.

ZMapp is a cocktail of three monoclonal antibodies. Its formulation was developed by testing different combinations of human–mouse chimeric monoclonal antibodies.

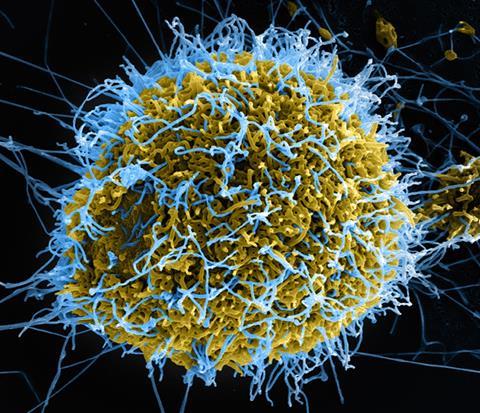

The filoviruses known as Ebola and Marburg are among the most deadly of pathogens, with fatality rates of up to 90%. The diversity viral strains make it difficult for researchers to develop treatments. Three strains of the Ebola virus are lethal to humans: Sudan, Bundibugyo and Zaire. Earlier this year, a new Zaire strain emerged in Guinea and quickly spread to Liberia, Sierra Leone and Nigeria.

The development of ZMapp and its success in treating monkeys at an advanced stage of infection is a ‘monumental achievement’, writes Thomas Geisbert of the University of Texas, US, in Nature.2 Geisbert notes that the authors used the Kikwit variant of the virus in these experiments, but they went on to show that ZMapp inhibits replication of the strain responsible for the current outbreak in cell culture.

Peter Piot, director of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) in the UK, agrees that the trial provides ‘the most convincing evidence’ to date that ZMapp may be an effective treatment for Ebola in humans. And Jonathan Ball, professor of molecular virology at the University of Nottingham, UK, calls the degree of protection offered by the new antibody cocktail ‘impressive to say the least’.

The consensus is that human trials should start as soon as possible. Martin Hibberd, professor of emerging infectious disease also at the LSHTM, hopes the Canadian team can secure funding to start clinical trials straight away. ‘[This] is a very well designed study with better than expected results, which give great hope for future clinical trials.’

Ebola vaccine trial set to start

If approvals are granted, UK research teams could start vaccinating healthy volunteers from mid-September in a Phase 1 safety trial of an Ebola vaccine. The Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council and the UK Department for International Development will allow a team led by Adrian Hill of the Jenner Institute at the University of Oxford, to start safety tests of the vaccine alongside similar trials in the US.

The candidate vaccine is against the deadly Zaire strain of Ebola and uses a single viral protein to generate an immune response. Pre-clinical research has indicated that it provides promising protection in non-human primates exposed to Ebola, without significant adverse effects.

The consortium’s funding will also enable GlaxoSmithKline to begin manufacturing up to 10,000 additional doses of the vaccine, so that if the trials are successful stocks could then be made available immediately to the World Health Organizsation.

No comments yet