Several companies based in Germany are suspected of selling compounds to Russia that could be used to make chemical and biological weapons like mustard gas or Novichok. The firms reportedly didn’t have the required permits for the transactions, so German custom officials are now digging into the case. Fifty officials were on site at the end of August to inspect ‘alleged violations of the Foreign Trade Act.’

Benedikt Strunz from the German broadcaster Norddeutscher Rundfunk (NDR), who is one of the journalists that broke the story, says that the companies have been the focus of the authorities for a long time. ‘Customs investigators have evidence that responsible persons at the company Riol Chemie presumably exported hazardous chemicals and laboratory supplies to Russia over a period of years,’ he says. According to the investigations, Riol Chemie alone has made more than 30 shipments in the last three and a half years, but Strunz points out that at least two other chemical companies and one export firm could be implicated too.

Riol Chemie was contacted for comment but didn’t reply.

Strunz notes that the substances involved are known as ‘dual use chemicals’ because they have both civilian and military applications. ‘Most of the exports went to the Russian company Chimmed,’ he says. ‘We were also able to show that Chimmed has cooperated with the Russian intelligence service FSB [Federal Security Service] and with military laboratories in the past.’ The research additionally revealed strong management links between Riol Chemie and Chimmed.

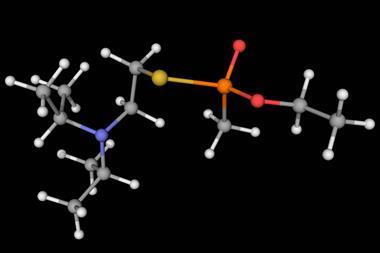

‘The traded chemicals included diethylamine, a potential precursor for the production of chemical weapons, as well as aflatoxin, a potential biological threat agent,’ explains biochemist Mirko Himmel at the University of Hamburg in Germany. ‘Additionally, chemical compounds were on the trading lists which could be used in analytical laboratories involved in food safety.’

Himmel says that although the types and quantities of traded items are at levels that could be explained by a legitimate use, he wonders why the firms have been trying to circumvent the legal processes. ‘Apparently, they traded these chemicals without having the appropriate export licenses, which would be in violation with EU and German export control legislation. In my view, a careful and unbiased investigation is needed to further clarify this.’ Himmel emphasises that violations of the Chemical Weapons Convention cannot be tolerated under any circumstances.

Strunz confirms that the amounts of compounds sold to the Russian company were very small, sometimes only a few milligrams. ‘These quantities would be too small for industrial production of chemical weapons. However, experts tell us that the substances could be used as samples to check the quality of their own production.’ Although he cannot disclose the complete list of suspected illegally exported substances yet, Strunz mentions that other trades may have involved chemicals like microcystin, a powerful liver toxin, and saxitoxin, a neurotoxic compound. Strunz carried out the research with colleagues from several German media outlets and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project.

No comments yet