The UK is facing a £7.5 billion bill to dismantle its 20 defunct vessels

The UK defence department has not scrapped any of its 20 defunct nuclear submarines in more than three decades, according to a recent public spending report. Storing the vessels has already cost the government around £500 million. But why has the UK left these submarines in dockyards for so long – and how difficult is it to dismantle them?

What is a nuclear submarine?

A ‘nuclear’ submarine can refer to a submarine that carries nuclear warheads, one that is powered using nuclear energy, or both. In the UK, the Vanguard, Astute and Trafalgar class submarines are all powered using a nuclear reactor, but only the four Vanguard class submarines carry nuclear warheads – Astute and Trafalgar submarines are ‘hunter-killers’ designed to sink other ships.

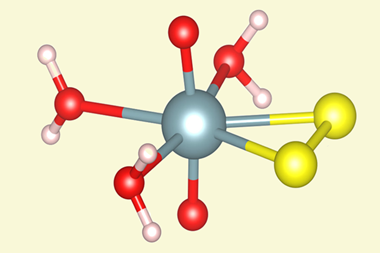

The UK’s current fleet relies on a reactor typically seen in power stations across the world – the pressurised water reactor (PWR). These compact power plants produce vast amounts of heat through the splitting of uranium-235 (235U). This fissile isotope exists in very small quantities (less than 1%) in natural uranium, which mainly consists of uranium-238 (238U).

To use it as fuel, the 235U is increased relative to the 238U in a process known as enrichment. In the PWR, waste fission products are made, such as caesium, xenon and krypton, as neutrons split the 235U fuel, with 238U also absorbing neutrons to form plutonium. These fission products can damage the ceramic fuel and reduce the reactor’s efficiency. The vessel that contains this whole process is also bombarded with high levels of radiation over its operational life.

What happens to a nuclear submarine once it is removed from service?

Once a nuclear-powered submarine is decommissioned, it is placed into long-term storage. Only after monitoring the vessel will engineers begin to defuel and dismantle it. However, over the past four decades, this second part hasn’t happened in the UK.

Since 1980, the UK Ministry of Defence has taken 20 nuclear-powered submarines out of service. Of these 20 subs, the UK has not fully disposed any of them and nine still contain highly radioactive nuclear fuel. The vessels have languished at dockyards in Plymouth and Rosyth.

This is not a sustainable solution, but it is in stark contrast with other countries’ past policies. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union dumped 19 ships containing nuclear waste in the Kara Sea, as well as 14 reactors and the K-27 nuclear submarine. With such vessels continuing to rust on the seabed, there are concerns these sites could harbour a potential environmental crisis.

However, the subs stored in the UK are constantly monitored in a controlled environment. Although a far cry from the Arctic submarine graveyards, the UK fleet still lies exposed to salty water, with the vessels rusting in the dockyards.

Why are the submarines still in storage?

It is an incredibly complex situation, but the government stopped defueling its disbanded fleet back in 2004. The UK’s nuclear regulator deemed that the facilities were not up to standards, and the UK has been working to improve them ever since. Mired in delays and inflating budgets, the defueling may not restart until 2023 – the original start date was 2012. Even when the subs are ready for their next voyage through the disposal process, it is a journey fraught with complexity.

What is the plan for the nuclear waste?

Once defueling starts, the sub will be moved to a ‘reactor access house’ on rails. In this facility, engineers will remove the spent nuclear fuel from the sub, which contains various actinides and radionuclides. The fuel is highly radioactive and generates heat, so needs to be cooled in water before any further work can begin.

To cool the fuel rods, the waste is sent to a specialised plant at Sellafield, where it is stored in vast water ponds. The water acts as both an efficient coolant and radiation barrier. Historically, this spent fuel would have then been recycled to form new nuclear fuel.

During reprocessing, the fissile uranium and plutonium is separated through solvent extraction, before converting the remaining liquid waste into a glass for long-term storage. However, it is now unclear whether this will still happen. It is more likely that the spent nuclear fuel will be stored indefinitely after cooling.

The current UK strategy is to bury this waste in a highly-engineered geological disposal facility, which would see more than 650,000m3 of waste stored in an underground cavern, according to recent government estimates. But plans are still ongoing and a facility is yet to be built.

What happens to the submarine after defueling?

After defueling, the sub will return to the ‘wet’ dock for another period of storage and monitoring. Following this, the submarine is dismantled. Components such as pipes and pumps exposed to radiation are taken away and the reactor vessel removed.

However, engineers do not simply remove the reactor. In many countries, the reactor is lifted out with the two empty compartments either side of it and then sealed off to minimise the risk of exposure. After removing this ‘three-compartment unit’, the submarine is cast off for its final voyage to a commercial shipyard for recycling.

But it will be a costly endeavour. The UK may face costs of up to £7.5bn if it wants to take the entire fleet through this voyage of defueling and disposal. It remains unclear whether the plans will stay on course, but the defence department has committed to dismantling the fleet ‘as soon as reasonably practicable’.

No comments yet