Scientists warn some monitoring could end in a matter of months and have appealed to the public for funds

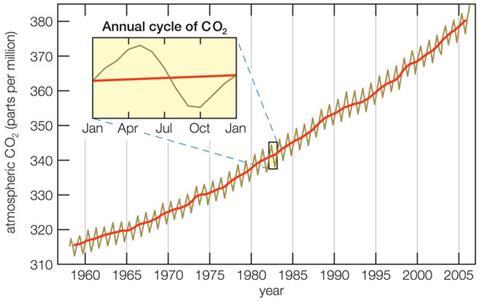

The future of the iconic Keeling Curve, a record of atmospheric carbon dioxide that has been kept for over five decades, is in doubt. Funding cuts have left scientists at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California, US, appealing to members of the public for donations to keep the work going. The scientists are now warning that to keep the carbon dioxide monitoring programme going, they will need to end their long-running work monitoring oxygen levels in a matter of months. If further funds cannot be secured the carbon dioxide monitoring programme is also at risk.

‘It’s at the point where if I don’t have funding for the programme I will simply have to shut it down,’ says programme leader Ralph Keeling, who posted a letter of appeal to the Keeling Curve website on Christmas Eve. ‘We’re short by around $400,000 (£243,000) for 2014.’

The Keeling Curve is a common sight in textbooks, and underpins countless studies, forecasts and climate change policies. Keeling’s father, Charles David Keeling, started the curve back in 1958, taking carbon dioxide measurements from the observatory at Mauna Loa in Hawaii that continue to this day. The programme has since expanded to include data from sites around the world, and has been tracking oxygen alongside carbon dioxide since the 1980s. ‘We learn a lot about what’s controlling carbon dioxide levels by looking at oxygen at the same time,’ says Keeling. ‘It’s another global metabolic measure of how the planet’s behaving.’

But the programme has suffered funding cuts in recent years. Problems began in 2010 when funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF) ended. A grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has also run out. The squeeze on the US federal science budget is only part of the problem, says Keeling, as the global nature of the programme makes it difficult to fit in with short funding cycles. ‘It’s pretty easy for any of the agencies to look at this as someone else’s problem,’ he says. ‘The closest match is NOAA, but they have been very strapped for funding recently, so it was very bad timing to try and find long-term secure funding.’

Scientists outraged

Despite lengthy negotiations through 2013, Keeling has not yet been able to secure additional grants from the NOAA or the NSF, and has had to cut staff and divert other funds to continue the oxygen programme. Crowdfunding could be one way to keep the measurements going until more federal funds can be secured in 2015. ‘The timeframe for this really makes it difficult: it’s short, it’s months,’ says Keeling. ‘I can’t afford to wait for an improbable process, I need to be trying everything.’

Climate scientists have voiced their shock and disappointment. Thomas Stocker of the University of Bern in Switzerland, who is co-chair of an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) working group, says he is ‘outraged’ Keeling’s group have been driven to such desperate measures. ‘The maintenance of these top-quality measurements are a global responsibility,’ he says. ‘This is not simply about perpetuating some nice-to-have monitoring, it is about maintaining a baseline of the most important driver of anthropogenic climate change, data which will serve thousands of scientific studies in the future.’

Sir Brian Hoskins, head of the Grantham Institute for Climate Change at Imperial College London, UK, agrees. ‘The thought that they’re looking for funding on the internet while funding agencies play pass-the-parcel is staggering,’ he says. He warns that public donations are unlikely to provide a long-term solution. ‘But maybe it will encourage some other foundations or benefactors to come forward,’ he adds. ‘In the end It has to be from some organisation, if not a government, to make it really last.’

No comments yet