A new mesoporous polymer combines optical transparency higher than glass with thermal conductivity lower than air. The material, which is easily made at the square-metre scale and should last decades, could be used to make insulating windows for energy efficient buildings.

Despite usually constituting less than 10% of a building’s external area, windows are responsible for around half the heat transferred in and out. To prevent unwanted heat loss, researchers are working to develop glass that is more thermally insulating while still allowing visible radiation to pass through.

Cellulose aerogels are one class of material that have been investigated for this purpose. As these consist almost entirely of air by volume, they do not provide a straightforward path for thermal vibrations to pass through the solid. Their small pores also help to prevent heat loss via convection. However, aerogels have a hierarchy of pore sizes, which means that even if the average pore size is much smaller than the wavelength of light – as required for transparency – some pores are inevitably large enough to scatter visible photons. As a result, the materials acquire a hazy ‘frozen smoke’ appearance.

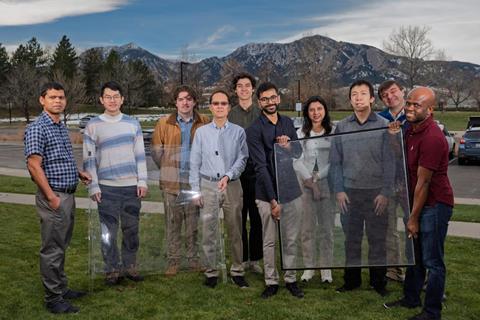

In the new work, Ivan Smalyukh and his colleagues at the University of Colorado Boulder, US, first produced a template by adding surfactant molecules to water. The surfactants self-assemble into structures called micelles, the sizes of which are determined by the molecules’ length. The researchers then added monomers of polysiloxane (silicone), which form a network around the micelles. ‘Then once we have a gel covered with polysiloxane, we wash away all the surfactant and remove water, replacing it with air,’ says Smalyukh. ‘All that you’re left with is a network of pipes that are all much smaller than the wavelength of light.’

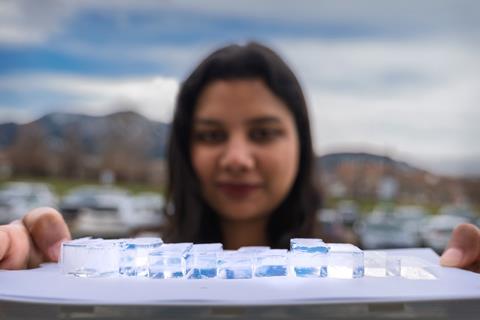

The material, dubbed Mochi (mesoporous optically clear heat insulator) by the researchers, is around 90% air by volume and therefore has a ‘frozen air’-like transparency, allowing 99% of visible photons to pass straight through. This is much higher than the 92% transparency achieved by window glass, which has a much higher refractive index and reflects photons at the interfaces. The Mochi’s structure also means that thermal vibrations propagate poorly through the material, which has a thermal conductivity less than half that of still air.

The researchers fabricated square-meter-sized slabs of the material by a process they believe should be scalable. As polysiloxane is already widely used to seal the edges of commercial windows, one straightforward application could be to insert Mochi between the panes of standard double glazing for better insulation. However, accelerated ageing tests suggest bare Mochi should last at least 20 years.

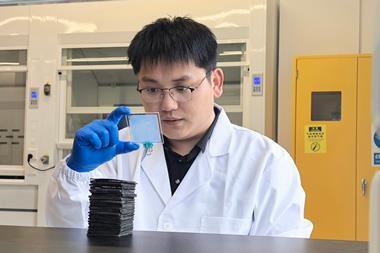

Mechanical engineer Longnan Li, from the Changchun Institute of Optics, Fine Mechanics and Physics in China, says that the production of large sections of insulating, transparent material ‘has been a big problem for previous studies’, and describes the US team’s findings as ‘a very significant advance’. ‘They’ve solved the problem that others studies didn’t of achieving transparency and low thermal conductivity,’ he adds.

References

A Bhardwaj et al, Science, 2025, DOI: 10.1126/science.adx5568

No comments yet